A cynocephalus, from the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

It was an angle of birds

directed toward

that latitude of iron and snow

advancing

relentlessly

along their rectilinear road:

with the devouring rectitude

of an evident arrow,

the airborne numbers voyaging

to procreate, formed

from imperative love and geometry.

—Pablo Neruda, “Migración”

I tend to assume that every concert, whether by conscious design or not, contains a coherent narrative of some kind. It might not be the most defensible assumption, but it is useful, to me at least; it gets me into a mode of listening that’s a little more engaged than it might otherwise be. That doesn’t mean the narrative is always plain, though. On paper, the June 17 concert presented by the Summer Institute for Contemporary Performance Practice (SICPP, known to the faithful as “Sick Puppy”), part of the institute’s annual week of new music training, festivities, and shenanigans, made some piece-to-piece local connections but seemed more miscellaneous on a global scale. In performance, though, a theme kept peeking around the edges, hovering peripherally, receding but then coming back into view. It took me a while to get a sense of it; I’m still not sure I got it. But it concerned two concepts that I have long been obsessed with, and that have been more and more salient in recent times: civilization and citizenship.

* * *

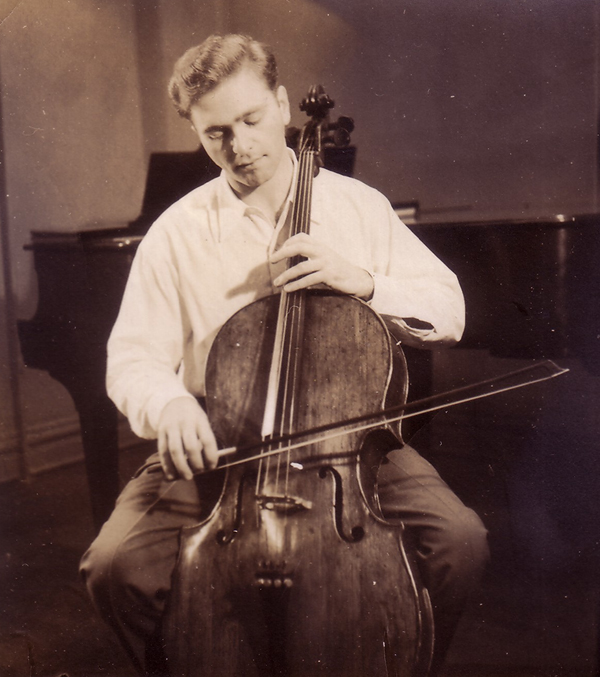

Citizenship of a musical kind was prominent. SICPP director Stephen Drury led off with a trio of piano solo works—big and fingerbusting, all past and future beneficiaries of Drury’s committed advocacy. And the concert was SICPP’s most full-fledged (though, sadly, unplanned) memorial to Lee Hyla, who had been scheduled to be the institute’s composer-in-residence. Roger Reynolds stepped in after Hyla fell ill, and programs later in the week featured much of Reynolds’s music, but this concert was Hyla’s—three pieces interspersed with other music that, directly and indirectly, provided comment and complement.

Hyla’s art was that of a model musical citizen who, nonetheless, maintained a wary distance from the more civilized—or civilizing—aspects of music. The raison d’être of Basic Training is a celebration of citizenship: Drury asked Hyla to write it as a tribute to Drury’s teacher, Margaret Ott. The piece itself, though, is a furious, sometimes funny, but ultimately equivocal portrayal of civilization’s progress. From a single-note, deliberately clunky opening (“Neanderthal-like,” according to Hyla’s program note), the piece acquires and deploys increasingly frenetic technique—it’s learning, WarGames-style. (My favorite aspect was how Hyla’s facility with complicated, off-kilter rhythms recreates the kind of distortions that happen when you can almost play something, hesitations and tumbles turning into their own determined groove.) The music consumes itself in virtuosity, then melts into a simpler, orderly, triadic coda; but the triad is minor, and the return of that single opening note, now rounded and polished into a beautiful object, is suffused with melancholy.

Basic Training constructs a culture; John Zorn’s Carny pulverizes it. It is Zorn in his full-on, Carl-Stalling-cartoon-collage mode: not so much a piece as a hundred different pieces run together for maximum slapstick contrast. Quotations abound in motion-blurred plenitude; stylistic signifiers come and go with near-subliminal swiftness. Carny is one of Drury’s specialties (he was one of its dedicatees), and the initial effect was simple astonishment at his fierce precision and energy. But the single performer and instrument, perhaps, gives Carny, for all its information overload, a kind of narrative unity: a montage-based secret history of civilized culture. The piece delights in exposing just how thin the line is that separates comforting dichotomies: tonal and atonal, old and new, high and low—and, finally, comedy and horror. Carny is funny until it’s not, the nonstop cartoon violence turning suspiciously lifelike.

Zorn reaches his coda by way of an outburst of clusters that Drury has called a “nuclear holocaust…. Are we now paying dearly for the previous fun and games?” Drury provided one possible answer by making a segue directly from Zorn’s fade-out ending into Frederic Rzewski’s version of the anti-war spiritual “Down By the Riverside” from his North American Ballads. Rzewski portrays that most crucial responsibility of citizenship—righteous protest—as invitingly easy, then perhaps too easy, then hard-won and triumphant, but then, as the music dwindles away, exhausting as well. That, in turn, gave Hyla’s We Speak Etruscan the air of a cautionary tale. The title of Hyla’s 1994 duo for bass clarinet (Rane Moore) and baritone saxophone (Philipp Staeudlin) references a lost civilization and language; in this context, the music’s truly impressive channeling of the instruments’ capacity for guttural honking sounded like an apocalyptic klaxon, a drive-by warning to turn around before it’s too late. As with Basic Training, the tone was primarily funky and fiery, but shaded by passages of lyricism shot through with minor-mode regret. Part and parcel of the civilizing impulse, Hyla seemed to say, is a wistful nostalgia for anarchic wildness.

* * *

If the first half was all about civilization and its discontents, the concert’s second half opened in back-to-the-land fashion—or, maybe, under-the-land. Chaya Czernowin’s Wintersongs IV: Wounds/Mistletoe (a world premiere) was positively tectonic, slow-shifting, granitic textures heavy with friction. The 17-player ensemble (conducted by Drury) was pitched toward registral extremes, all low growls and high whines, with microtonal abrasions and lots of white noise: snares, cymbals, breath sounds from the winds and brass. Not all of Czernowin’s effects came off—having all the wind players whisper over the mouths of plastic and glass bottles, for instance, was a provocative visual but proved barely audible. But the piece arrived at some great, punishingly bright, skull-rattling sonorities. Like magma, Wintersongs IV moved slow but, eventually, burned hot.

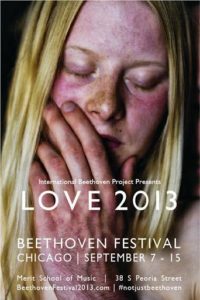

Hyla’s Migración, one of his last pieces (it was premiered in February by the SICPP-affiliated Callithumpian Consort), seemed appropriately airy by comparison. The text is a long Pablo Neruda poem considering natural cycles, winter and spring, life and death. But a tension between the individual and the collective is ever-present. The migrating birds of the title are considered as a machine, a product of technology: “a squadron of feathers, / an ocean liner / fluttering in the air.” The “transparent ship / constructs unity from many wings.” Neruda’s “multiplied hungry heart,” in Hyla’s setting, becomes something like a crowd of strangers on the same ferry.

A mezzo-soprano (Thea Lobo) sings (and, at one point speaks) the text in an equable but relentlessly declamatory style, the nine-player ensemble (conducted, again, by Drury) quilting an accompaniment out of instrumental aphorisms. Neruda’s conflation of evolved and constructed has a timbral echo, an often-yoked trio of piano, harp, and cimbalom, feathery and discrete at the same time, a quiet purr of rivets. The trajectory of Migración felt less conventionally expressive than meditatively compulsory: a reflective commute rather than an adventurous voyage.

Like many a commute, Migración led into a teeming urban grid, Charles Ives’s Set for Theatre Orchestra, with even the ensemble arranged on stage as if by zoning committee: percussion on the north side, timpani on the south side, winds and strings ensconced on the east and west sides, the piano centrally parked. The middle movement, “In the Inn,” was saturated with volatile ragtime, anticipating and recapitulating that thread from Hyla and Zorn and Rzewski. And the third movement, “In the Night,” with the sound of extra instruments drifting in from offstage suburbs, was gorgeous. But it was the opening movement that resonated most with the second half’s town-and-country unease, and the program as a whole: “In the Cage,” brooding, stalking, its leopard in the zoo pacing its pen, and the boy outside wondering as to the nature and benefit of the civilizing bars.

* * *

Pablo Neruda himself had an attitude toward citizenship and civilization similar to Hyla’s, an acute sense of the gap between an artist’s individuality and an artistic movement within society. In a 1971 interview with Canadian radio, Neruda denied that he was a political poet:

I am the poet of the moon, I am the poet of the flowers, I am the poet of love. Meaning I have a very old conception of poetry, which does not contradict the possibility that I have written, and that I continue to write, poems that are dedicated to the development of society and to the power of progress and of peace.

In the end, the thread tying together the concert was that the music never contradicted the possibility, either. Civilization was regarded with skepticism, but still engaged with it energetically and even exultantly; the citizenship on display was constantly reaching out, expanding the network, reweaving the web. The evening’s music squared the circle of the contemporary avant-garde, how the often grim nature of the modern condition can yield such exuberant art, how encyclopedic determinations of style and craft can create the freest expression. The concert postulated its own conclusion—civilization is technique; citizenship is love.