These golden weeks of early fall are the perfect time for Chicagoans to get outside and engage our senses. Perhaps, with the help of composer and sound artist Ryan Ingebritsen, we might engage our sense of listening in particular.

When I heard about Ingebritsen’s Song Path project — a venture that began in 2010 as a series of “sonic guided tours” of Minnesota State Parks — I jumped at the chance to speak with him about it. The Song Path idea intrigues multiple layers of my existence as a musician, lover of nature, and meditator. For Ingebritsen, Song Path is a practice that explores guided meditation and hiking as a compositional form.

Ingebritsen recently designed a Song Path hike at the North Park Village Nature Center on the outskirts of Chicago. I caught up with him to chat about what it means for a primarily electronic artist to lead troupes of people through the woods.

Ellen McSweeney: You work a lot with electronic media, from the Millennium Park sound system to electrified sewing machines. But when you described the Chicago Song Path event, you emphasized the lack of microphones and electronic equipment. Is it refreshing for you, to just work with nature and the human ear?

Ryan Ingebritsen: When I first started working with electronics, it was actually quite a leap for me. Up to that point, I had viewed myself as an acoustic composer who would not get involved in electronics or amplification. In those days there was much more of an aesthetic separation between the two trajectories, at least at music conservatories. But I found that I was always wanting to orchestrate in a way where one sound kind of emerged out of another, and wanted to literally have one sound “become” another and embody something of the other sound. That is when I started working with electronics and amplification more seriously. That led to a career-long obsession with interaction and the interactive process, which in turn led to my obsession with interdependent performance practice between artists of different media or disciplines.

I’d spend hours in the studio with sound, listening to the subtle details that made up those sounds. And in performance, I often play the role of sound environment manipulator, focusing on the specific sound environment in which the performer and audience live. So in a sense, what I do with Song Path is not much different from my live performance practice. I’m just moving an audience through an existing space to create a composition, rather than manipulating a sound environment while they sit in one place.

EM: How did you first come upon the idea of Song Path, and how has the practice evolved for you in recent years?

RI: I first started to consider the idea of Song Path while just hiking through the woods with my wife Shannon on camping trips. I would find myself in a place with interesting sounds, like a swamp with lots of frogs or field of crickets, and would notice how sometimes these sounds seemed to appear almost out of nowhere and at other times increased gradually in a very dramatic way.

I think one such specific hike at Starved Rock State Park really got me interested in the idea of doing it as a musical event. The various cavernous spaces that had been carved by water over millions of years seemed to imply different “rooms” for which short pieces could be composed. An audience could hike from location to location and hear a multi-movement work.

I got my first opportunity to really develop the Song Path in 2010 through the support of a McKnight Foundation Visiting Composer Fellowship to Minnesota. In certain spaces, such as Whitewater and Banning State Parks in Minnesota, I found that placing musicians around the park to make noises in very specific locations allowed various sonic elements to be revealed. But my intention with putting them there was only to instigate something that was already present in the space. For example, some natural reverberations exist in a valley when one yells in a specific acoustic node. Put a drum in that node, and a spectacular sound is revealed.

EM: Are walks like these a way to rebalance and refocus your attention, in a world where 24/7 headphones and sonic overload are everywhere?

RI: I think that it is an opportunity to teach the audience to experience their environment in a different way. The head of interpretive programs at Whitewater State Park once told me that after engaging in a purely sonic meditation with his eyes closed, he felt that all of his senses were heightened. I have noticed this myself. Colors seem a bit more vivid and smells a bit more strong. Maybe there’s even a little bit of euphoria.

I will say that a heightened awareness of one’s environment can also be quite a shock to the system, as evidenced by a quick trip I took to Chicago in the middle of the first set of hikes I did. Just getting out of my car onto Western Avenue nearly knocked me over.

EM: Have you ever charted an urban Song Path? What are some of the sonic spots in Chicago that you might put on such a walk?

RI: I have done this for myself a few times, though never with an official audience. One such hike was in Millennium Park. You start it in Lurie Garden, a place that exists because of a man-made structure atop a parking garage that was dug out of a landfill built over 100 years ago that used to be part of Lake Michigan. Then, a garden was planted that reflects the natural landscape that would have existed at that time where a bustling city now stands. We often talk about the intrusion of mankind on nature. This feels more like the intrusion of nature on a man-made environment. It gives you a very small taste of what the place may have sounded like years in the past. But the garden itself also provides a sonic shield from the surrounding city.

I tend to gravitate towards locations where the natural sound environment and man-made sound environment intersect in some specific way. That’s not hard to get, since a sonic landscape untouched by man-made sound almost does not exist on the planet anymore. My friends Eric Leonardson and Dan Godston, associated with the Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology, have also done hikes in urban spaces, though perhaps with a slightly different aesthetic focus.

EM: What kinds of folks turn out for the walks, and what sorts of reactions and experiences do you witness while leading the walks?

RI: My first round consisted mainly of people who were camping in the Minnesota parks. I literally went tent to tent and talked to people, as did the park rangers. So I had quite a mix of people: from members of the arts scene in Minneapolis to people who were not aware that classical music was something that people still did. Some people said they could not think of what they were experiencing as “music,” but found it a profound experience. I am interested in what that experience is much more than I am interested in what it is called.

Many of my family hikes were attended by parents who were hunters. They said that what I had been doing in the woods — listening deeply and trying not to disturb the natural surroundings so I could hear everything — was very similar to the practice of hunting, or at least what some of them referred to as “real hunting” where it’s just you and the animals: no traps or other tricks. Animals are so sensitive to what they hear that any small movement or noise you make will disturb them and give them some sense of danger. This kind of hunting is a practice of listening more than anything else, and they spend hour upon hour, day after day doing it each season.

I had a hike where a group of atheist hippies from Minneapolis walked alongside a couple that was taking a road trip across the USA visiting different mega-churches. It is rare that a musical experience can engender such commonality among different groups. Musical communication often relies so much on idiom, which in itself often has social or perhaps even political implication. I’ve seen people almost get into physical fights over musical taste, in arguments far more heated than any political debate I have ever seen. But the experience of the hike seems to help tap into something a bit more universal.

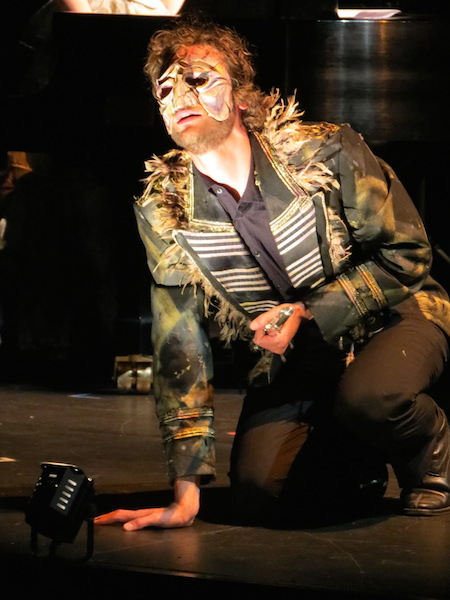

Ryan Ingebritsen is the composer of 3 Singers, an innovative opera/sound installation created in collaboration with director and choreographer Erica Mott. The piece will have its Chicago premiere in January.