Kudgel, at The Middle East Downstairs, Cambridge, Massachusetts, October 4, 2014.

Some rituals are abiding. Boxers touch gloves prior to the start of a bout. Dogs turn around before they lie down. And bands, at some point before they stop playing, direct your attention to the merchandise table.

Near the end of Crazy Alice’s set at The Middle East Downstairs in Cambridge on October 4—the band’s first performance in over a decade—the reflex kicked in. “If you guys want any Crazy Alice CDs,” lead singer Jeff Ahearn announced, “come over to my house, we’ll go down to the basement.” He grinned. “I got a shitload of ‘em.”

* * *

This fall, Pipeline!, the local rock-punk-indie showcase that airs weekly on WMBR, MIT’s student-run radio station, is offering a series of opportunities to rummage through old boxes of Boston rock and roll. The program’s playlists and in-studio live sets have long refracted a kind of Platonic ideal of college radio alt-rock through the transient prism of local bands. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, Bob Dubrow (host from 1993 until 2003) has organized no fewer than thirteen shows, a pageant history of the city’s underground rock scene. The most prominent feature of the shows—reunions, dozens of long-defunct local bands getting back together for one more blast—is a testament both to Pipeline’s years of advocacy and, in a more ironic way, to rock and roll’s penchant for attritional Darwinian churn.

The number of shows, and their organization, also demonstrates another rock penchant, categorical subdivision. Choose your stomping ground: mine was the October 4 show, circling (with a couple of outliers) the twin poles of post-punk and hard rock. Much of it was its own form of historically informed performance, a snapshot of a particular early-’90s aesthetic. Interestingly, I might instead have sampled the present: also that day, the Boston Music Awards were presenting a day-long event called “Sound of Our Town,” at a relatively new place (The Lawn on D, a prefab public green in Boston’s self-proclaimed Innovation District) and featuring a cross-section of current stars: Speedy Ortiz, Dutch ReBelle, Eli “Paperboy” Reed. Instead, my love of antiquity won out. But it did raise the question: what, exactly, does this town sound like?

This Pipeline show was heavy on the aforesaid reunions: not just Crazy Alice, but also noisy pioneers Kudgel, alt-fuzz purveyors Bulkhead, the pop-metal stylings of Orangutang. To close the evening, Nat Freedberg (better known around town as Lord Bendover, the rococo front man of novelty-rock act The Upper Crust) reassembled The Clamdiggers, his early, surreal surf-rock project. (To my everlasting sorrow, I am sure, I had to miss Orangutang and The Clamdiggers; Saturdays are work nights for me.)

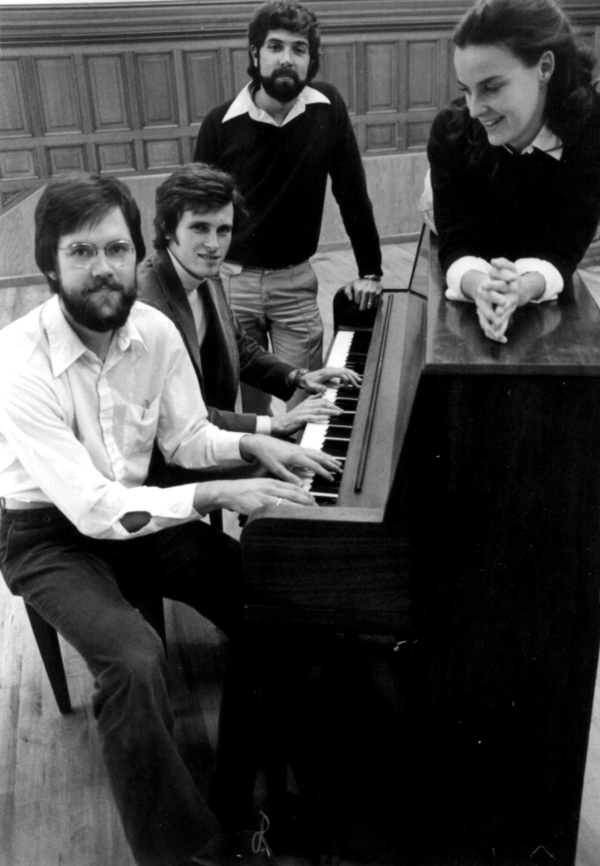

Thus the subdivision contained further subdivisions. Crazy Alice’s punk-tinged power chords, tight, chugging, and chiming with distortion, was followed by Quintaine Americana: high-proof, southern-tinged heavy hard rock, lead singer Rob Dixon delivering gothic vignettes in a penetrating, snarling drawl. Kudgel was perhaps the most anticipated blast from the past, and a blast it was: gleeful, grinding howls of pop-punk—the so-called “chimp rock” that, along with fellow Boston band The Swirlies, the group invented. Singer/guitarist Mark Erdody hunched over his stand mic (a tortuous posture first adopted, according to Erdody, so he could sing and keep his eyes on the fretboard at the same time) and laced each number’s sing-song shouting with a childlike delight in the profane.

The minimalistic new music/jazz fusion of Birdsongs of the Mesozoic was the evening’s biggest contrast, quieter, precise, carefully arranged (everyone used music), intricately cool. Addressing the audience a little later, Dubrow acknowledged that the group was included as “a palate cleanser.” Still, the ensemble could claim appropriate lineage, having been started, many iterations ago, by Mission of Burma founder Roger Miller (not in attendance) and his one-time Moving Parts bandmate Erik Lindgren (still manning one of the two keyboards). And the group paid homage in their own way, at one point mashing up ex-Velvet Underground local hero Willie “Loco” Alexander’s “Basket Case” with the “Spring Rounds” from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Bulkhead, a quartet that ventured near alt-pop stardom in the ’90s, was a louder form of cool: a haze of feedback-laden hooks, lead singer Peter Ryan spinning out wordy rambles of lyrics.

If it wasn’t quite Boston rock royalty, it was at least a slice of the aristocracy, the landed gentry, as it were. But, even at that, there wasn’t much of a common, distinctive sound among the groups. Maybe there is no real sound of the town. Maybe the sound of Boston—a port town, after all—is the sound of whatever comes ashore that week, year, decade. Still, there was something of a shared quality. I will say this: Boston loves its exemplars—those acts that either are so singular as to make (and, sometimes, break) the mold, or that so fully embody a sound, or a genre, or an attitude, as to aspire to a kind of universal standard. On the former side was Kudgel’s self-proclaimed, happily confrontational chimp rock, or Birdsongs of the Mesozoic—classical, rock, and jazz thrown into a diner milkshake machine. On the latter was Crazy Alice, Quintaine Americana, and Bulkhead—pop-punk, southern rock, and left-end-of-the-dial alternative, respectively, all served neat.

* * *

For me, the concert was a pleasantly odd bit of temporal dislocation. I moved to Boston in 1994, in time to dive into the particular scene the evening’s bands largely evoked—hardcore and its similarly loud discontents, holding court at the Rathskeller or Harpers Ferry, those lost, louche temples of disorder. But 1994 was also right around when Kudgel broke up, and Bulkhead broke up, and Orangutang broke up. (Crazy Alice held on for a few more years.) So the experience was less nostalgic and more like opening up a time capsule. For sure, though, nostalgia was a big part of the evening. For once, a rock club audience actually skewed my age, or even a little older. Graying hair—or no hair—held sway on stage. A lot of the shout-outs were to the deceased. But there was no sentimentality; these were once and future punks, not inclined to go quietly, preferring to mosh against the dying of the light. Kudgel had spent one chorus hammering away at Willard Motley’s old mantra of hedonism: “Live fast, die young, leave a good-looking corpse.” Most of the performers still seemed to be aiming for best-two-out-of-three.

If there was an honored ghost for the evening, it was Billy Ruane, the late, legend-in-his-own-time promoter, The Middle East’s longtime booking guru, a mad dervish of enthusiasm and a nucleation point for so much of the city’s rock-and-roll fizz over the past three decades. Every band offered posthumous fealty. A highlight of Birdsongs of the Mesozoic’s set was saxophonist Ken Field’s “Ruane,” a funky, unpredictable box of musical knives. Kudgel brought out their own icon: an old bass drum head, mounted on a stand and emblazoned with the words “Thank God for Billy Ruane.” It remained on stage for the rest of the evening.

If it made the whole experience feel a little bit like an Irish wake—for a colleague, for a period, for a scene—well, there are plenty of things worse than a good Irish wake. And besides: isn’t literature’s most famous Irish wake also an avant-garde expression of eternal renewal? Riverrun, past Harpers and the Rat, from swerve of railyard to Back of Bay: the Pipeline still flows.

![jerome_logo[1]](https://newmusicusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/jerome_logo1.jpg)