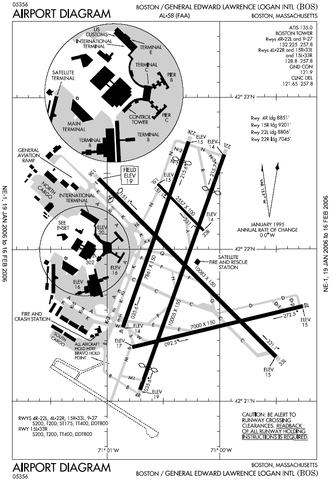

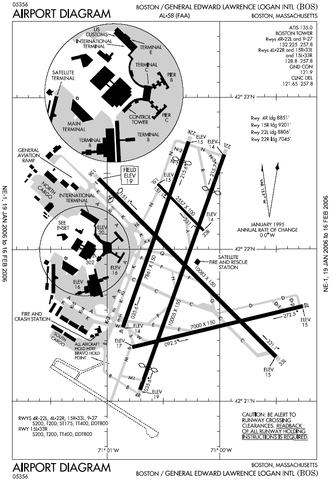

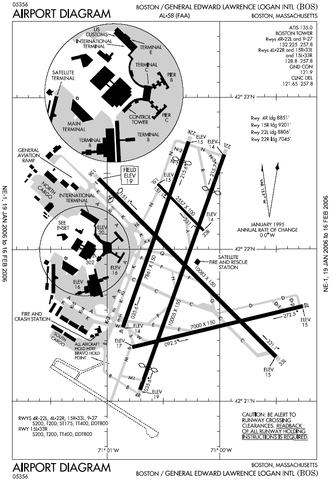

Logan International Airport in Boston. (Via.)

If the only thing you ever saw of Boston was Logan International Airport, first of all, my deepest sympathies and, second, your idea of the city might very well be populated only by minutemen, the Red Sox, lobsters, and Cheers. Every city with an airport, I think, has an airport version of itself, based on the cultural shorthand of the souvenir stand. Airport versions of cities are not wrong, exactly, just disorientingly oblique to the people who actually live in those cities. But the airport version of Boston isn’t for me; it’s for tourists. It’s for people who have never seen the place before. It’s like a bullet-point outline to be (hopefully) filled in somewhat over the course of a visit. I’m probably too embedded and too oblivious to accurately judge the usefulness of the airport version of Boston. But I could imagine that it would provide as good a toehold as anything. (A couple years ago, I visited Barcelona for the first time. The airport version of Barcelona was Gaudí, Messi, and ham—in retrospect, a reasonably efficient triangulation.)

I sometimes wonder if, several decades from now, people will look back on the current era of new music and characterize it in terms not far removed from tourism. Because if there’s one thing common to the various kinds of music going under the new music banner right now (and a lot of music beyond that), it’s the pursuit and/or assertion of an aura of authenticity. Traditions, styles, vernaculars—so many new pieces I hear these days pledge allegiance to some form of authenticity, some repertoire, some community. A lot of times, such pieces are the result of a deep engagement with the cited style on the part of composer and performer; a lot of times, it’s simply an expression of momentary curiosity. But much of the listener’s intended satisfaction is to come from the feeling that the experience has been both unfamiliar and authentic. In other words: the ideal tourist experience. Which means that the real version and the airport version might, in fact, be equally effective.

***

On November 2, in the cool, enveloping reverberation of Boston University’s Marsh Chapel, the Lorelei Ensemble, artistic director Beth Willer’s eight-voice all-female choral group, presented a program called “Reconstructed: The New Americana,” venturing in and around an increasingly popular ethnomusicological destination: shape-note singing. The concert sent postcards from the style’s antecedents—colonial hymnody (via its most idiosyncratically great practitioner, William Billings) and folk music—while also placing it in new, modern galleries: four world premieres were interspersed with contemporary additions to the shape-note repertoire.

Early American hymnody and shape-note singing might be two of the most quintessentially American musics there are, in that they live at a nexus of American anxiety—the disconnect between the way the country ought to be and the way that it actually is. Both were aspirational forms, specifically designed to be specifically American, and both were, in turn, often rejected as being too provincial and unpolished. You only really get a sense of this stew of influence and counter-influence in the context of its relatives: the more buttoned-down, reactionary New England hymnody of the later 18th century, African-American gospel, Gilded Age grandeur, maybe even modern Christian rock-pop, a continuous negotiation between exaltation and populism.

All by itself, though, and in Lorelei’s unfailingly, uncannily pure and precise voices, the style found itself at another intersection: the shared Apollonian streak in the early music and modernist strains of classical music. It was certainly something common to the four commissioned works (the commissions supported—full disclosure—by NewMusicUSA). All of them, for all their variety, were dedicated to the not-inconsiderable pleasure of close-packed straight-tone harmonies, soaring echoes, and perfect intervals sung with overtone-sparking exactness. That melange of very old and very new was layered throughout the concert, even in interludes—flutist Ashley Addington and violinist Shaw Pong Liu improvising the familiar strains of “Amazing Grace” into sometimes surprisingly loose translations.

Scott Ordway’s North Woods, interpreting the Maine landscape through the lens of the ancient Roman historian Tacitus’s imaginary descriptions of northern Europe, made use of the most immediate sensation of the choir’s phenomenal purity: clean clarity as cold as ice. But the piece also hinted at the change from wild to civilized, from frontier to familiar destination. With Addington’s piccolo glinting off the music like lens flare, the opening movements were built on a foundation of fast, quasi-aletoric chanting, the ground continually slippery and shifting. By the end, though, the boundaries had been set down: as the first movement’s text circled back (“The nights are dark; the earth casts only a low shadow”), the music coalesced into a kind of domesticated part-song, as if the place itself had finally been fully marked off and mapped.

Joshua Shank’s Saro arranged variants of an old folk song into a quiet allegory of barriers and discrimination. The music, too, took on a notable echo of modern production. Starting out in familiar territory—a poignant solo encased in open intervals and diatonic suspensions—the harmonies gradually blurred into one another, the melody itself detached and slowed down into pure sonority, real-time digital stretching realized in analog form. With Shaw Pong’s violin hovering like a ghostly narrator, the piece felt both contained and unsettled. Mary Montgomery Koppel’s Nokomis’ Fall also used an instrumental anchor—Addington again, this time on bass flute—adding both texture and anchor to her twisty harmonies. Setting a passage from Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, Koppel emphasized the twice-told ritual aspect of the story with unabashed text-painting; when Nokomis (Hiawatha’s grandmother) finally is plunged from the moon to the earth like a meteor, Koppel laced the scene with a simple, descending whole-tone scale in the flute, obvious and ingenious at the same time.

The most ambitious of the new works was Joshua Bornfield’s Reconstruction, a five-movement a cappella “mass” replacing the rite with 19th-century hymns from the shape-note lineage. (The movements were spread throughout the concert.) The treatment was equally ambitious: “Crowns (Mercy Seat)” turned into a polytonal, polyrhythmic contest between sopranos and mezzos; “Wrath (Battle Hymn of the Republic/John Brown’s Body)” and “Brother, Sister, Mourner (Amazing Grace)” re-energizing their familiar sources with busy Ivesian collages; “Farewell (Long Time Travelin’)” a tide of continuous, exotic reharmonization; and the finale, “Salvation (Song to the Lamb)” dense with melismatic decoration and closing on an open-ended, clustered “Amen.” It was a challenging score, superbly sung, hinting at hidden complexities even beyond its mercurial surface.

The newer shape-note hymns—all from within the past 20 years—pushed boundaries in a more casual, unassuming manner. Dana Maiben’s “Vermont” mixed a bluegrass-like melody with harmonies echoing the great 20th-century Anglican composers, major 2nds and 9ths in luxurious sequences. Adam Jacob Simon’s “Inman” gently hovered between natural minor and relative major, a swirl confined but unresolved. Moira Smiley’s “Utopia” was the most reminiscent of William Billings, a bricolage of modal collisions. The Billings selections (“Africa” and “Taunton”) were themselves transformed, the translation into upper voices revealing Dowland-like strains among his dizzyingly individual counterpoint. Even the most familiar attractions can seem new, if you happen to visit at just the right time.

***

Tourism was all over Roomful of Teeth’s November 21 concert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Kresge Hall. The group itself is the musical equivalent of a compulsive traveler, always adding new and farther-afield techniques and traditions to its toolbox. The appearance was the culmination of that ever-more common form of musical furlough, an academic residency. But the bulk of the program—two premieres, both by MIT composers—were works and music about tourism, in both the symbolic and literal sense.

The first half was Elena Ruehr’s one-act, a cappella opera Cassandra in the Temples, to a libretto by Gretchen E. Henderson. It was presented in an oratorio format; Ruehr, introducing the piece, indicated an eagerness to see it staged. Depending on the director, such staging would either be a trial or a delight: the libretto is more provocative than narrative, more about mood than story. Henderson’s poetry is jammed with wordplay and device, full of near-homonyms and compounding linguistic echoes in a way somewhere between Gertrude Stein and Van Dyke Parks. (Much of it hinges on the text’s visual appearance on the page, which unusually elaborate supertitles attempted to convey.) There is a framework, one centered around tourism: a modern visitor approaches the grave of Cassandra, the legendary Greek prophetess, the visit igniting a parallel retelling of Cassandra’s own crucial visit to the temple where snakes licked her ears, providing her with her gift and curse. Apollo makes an appearance, as does Laocoön and Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, but everything passes as shadows behind the scrim of language.

Ruehr’s music is luminous, constantly musicalizing the sounds of speech in creative, even cheeky ways. A chorus of whispers, like brushed cymbals; sea serpents and snakes sized up in voiced sibilants; Cassandra and Clytemnestra, trapped in their fates, the harmonies sloughing downward along the flat side of the circle of fifths. The score makes good use of Roomful of Teeth’s ability to switch styles on the fly, from throat-singing drones to seething dissonance. (My favorite was Cassandra’s rejection of Apollo—in Henderson’s version, a single “no” slithering down the page—set as sunny, strident ’60s pop, a girl knowing all too well whether or not he’ll still love her tomorrow.) I still can’t imagine exactly how it would be staged, but an abstract Cassandra in the Temples was still plenty diverting, in every sense of the word.

The other premiere, Borderland—a collaborative piece by Christine Southworth and Evan Ziporyn—also began with tourism, in its most nightmarish form. The subject is the conflict in the Ukraine, but half of the piece, its first two movements, viewed it from the vantage—first from the air, then from the ground—of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17, shot down over the country on July 17. A Facebook post, in Dutch, by a boarding passenger was combined with a tweet, in Malaysian, from the airline announcing the disaster, into a staccato weave of open- and closed-mouth sounds—shock and stoicism, perhaps. Then intercepted communications (referencing the weapon used to down the place) between the rebels on the ground and their Russian contact became a tangram of short, repeated fragments, busy, circling crosstalk, anchored around the phrase “А куда нам” (Where are we?). The last two movements turned to Ukranian poetry, by Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, and Bekir Çoban-Zade, set with overtones of birdsong, chirping and chattering behind longer, keening lines. The textual sense was that of an eternal nature regarding passing humanity, the point of calamity giving way to a kind of persistent sadness in the land itself.

The musical setting made use of both minimalistic mosaics of motives and vocal extremes: the Shevchenko poem, for instance, alternated between very low and very high, around an accompanying middle ground, and the last movement, too, placed the texts in (perhaps intentionally) vowel-distorting ranges. For both Cassandra and Borderland, the group used sheet music while its director, Brad Wells, conducted, which actually amplified more than alleviated cautious singing. The concert’s closing three works, by contrast, were Roomful of Teeth standards, performed from memory: Judd Greenstein’s Run Away, gorgeous, simple yet shifty pop harmonies filtered for maximum warmth; Wells’s Otherwise, an exercise in pushing vocal sounds to margins both rich and strident; and the “Allemande” from Caroline Shaw’s Partita, goofy and joyous—and still, I think, the single best demonstration of what the group can do, an extensive tour of the surroundings with an indefatigably, generously, genuinely enthusiastic guide.

***

In The Wicked + The Divine, the ongoing comic book series by writer Kieron Gillan and artist Jamie McKelvie, Cassandra is a journalist, casting questions and camera at the gods-reincarnated-as-pop-stars that are the book’s central mythological conceit. At the outset, the shallowness with which the celebrities inhabit their supposed divine roles fuels Cassandra’s skepticism into flame. “You know what I see?” she snaps. “Kids posturing with a Wikipedia summary’s understanding of myth.”

She’s wrong; they really are gods, with all the attendant powers and arrogance. But she’s also right; they are kids, become gods, with a very incomplete sense of who those gods are or what it all might mean. They are, in essence, existential tourists, trying on the airport version of a divine identity with the hopes that their visit will invest that identity with nuance and depth. And besides: it doesn’t matter. They are still worshipped. Their performances still matter. As the comic’s main, human character responds to one such performance: “I don’t understand a word she’s saying. Nobody does. All we know is that it means everything.” The great advantage musical tourism has over its physical counterpart might be that the terminal can be just as inspiring as the countryside.