So far throughout this series on the recording studio and the collaboration within, I have provided a primer on what producers are and what they do, my process of producing non-classical music, how classical music production differs from non-classical, and ways in which classical music production could evolve with contemporary composition trends. For this last post, I’d like to offer up five suggestions for those who may be new to the studio experience—either as a producer or performer—or for those who would like to take their future projects in a new, collaborative direction.

Communicate

A point that deserves to be reiterated is the importance of communication in creating a healthy and successful collaborative environment. This means talking through ideas, providing feedback, asking questions, as well as being an active listener. Communication is a two-way channel. Not only is it important for you—whether you are the producer or the artist—to communicate your thoughts, but it is equally important to listen to others involved. As the producer, this is crucial for creating a strong working relationship. I have been in sessions where the producer only gave orders and hardly listened to the artist’s ideas. It creates a bitter relationship and a hostile environment in which no creative process could ever be fruitful.

From the producer’s perspective, listening to the artists you are working with will give you a better understanding of what it is they are trying to achieve. If you are working with musicians who are not as familiar with studio processes, their ideas may not work out the way they are imagining. However, listen to their ideas to help them achieve the end goal they are envisioning. For performers, it is important to go into a project understanding that the producer is there to help you achieve the best outcome possible. Listening to your producer and offering feedback only strengthens the project and deepens your understanding of what is possible in the studio.

Trust your team (i.e. don’t take your engineer for granted)

Part of the communication process I listed is to ask questions. What I mean by this is that, specifically as a producer, you should not feel like you need to have all of the answers. In a studio session, you are collaborating with a team of professionals. Whether it be performers, songwriters, or engineers, each person has a wealth of knowledge to contribute that you may or may not have. Take advantage of these resources and ask questions. Every composer knows how important it is to consult with performers about the extensions and limitations of their abilities on an instrument. This is the same for producers; ask questions and learn about fields you may be unfamiliar with. If a performer needs to adjust their tone to better sit in the mix, defer to their expertise on the instrument and ask what options there may be.

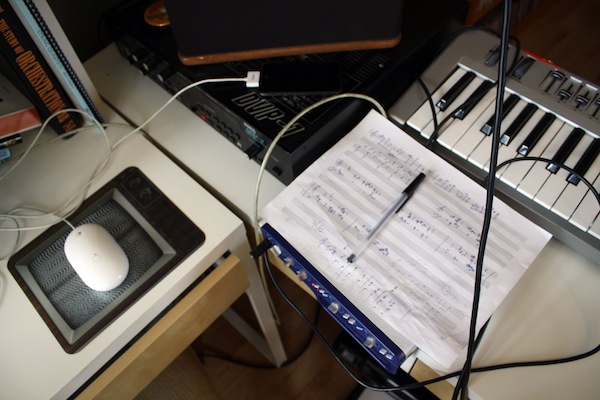

On more than one occasion, my engineer has provided invaluable insight that changed the course of the session and created a better end result. There have been times in which I was so focused on the musical material of a song that I wasn’t thinking about the sonic impact of each section. Suggestions about which areas of the sonic spectrum were lacking have pushed me to change the way I approach a section—sometimes by writing new parts to complement existing parts, other times by omitting parts I thought were necessary but realized were just a distraction. All this is to say, never take engineers for granted. They are more valuable than just turning a few knobs and hitting record. Even if they’ve only been in the role of engineer, they’ve been in the room with countless other producers and performers. They may just have a few tricks up their sleeves.

Have a plan (but don’t get too tied to it)

When preparing to produce a project, I always begin well before the first day in the studio. This includes doing research, studying references, studying scores, pre-production, and general conversations with the performers about what it is they are wanting to do stylistically. I always come to the first day of recording with a plan. This plan isn’t always extremely detailed, but it is an aid in organizing the upcoming sessions to ensure that everything gets done in a timely manner. The reason I tend not to prepare an overly detailed itinerary is because these plans almost always change once recording begins. It is valuable to be flexible and not get tied to a set way of doing things. These changes come about once a solid workflow is established and it is evident where the most time will be necessarily spent. However, having the initial plan will help you stay organized once things are set in motion and pieces of the schedule begin to move around. Performers will look to you to lead the way and get things rolling in the studio, and having a strong start sets you up for a successful and organized project. One of the roles of a producer is to maintain organization and keep the artists on track to meet their deadline. Doing your research ahead of time and having a foundational understanding of what the artist is wanting to achieve will keep you from wasting time during the recording process.

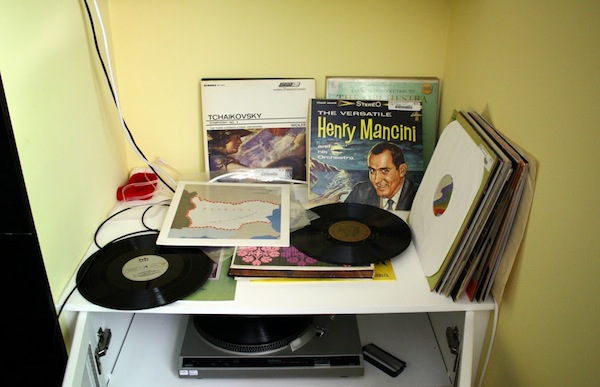

From the artist’s side of things, one way to help prepare for your studio sessions is to have at least an initial reference for what you are wanting to achieve sonically. Your references can be a combination of sources and they don’t necessarily need to all be things that you like. Knowing what it is you don’t like is also a helpful resource for the producer and engineer. Having an idea to get the conversation started is a great way to begin the pre-production process.

Push boundaries

One thing that I often see get lost in the studio is the spirit of exploration and experimentation. Of course, time and budget constraints can limit what people will be able to do, but, for those who are willing, the studio is an ideal environment for pushing boundaries. In a studio setting, you have the luxury of being able to hear an idea come to life in real time, and nothing is permanent if you don’t want it to be. As a producer for non-classical artists, I love offering up suggestions that are outside of the box. Sometimes they stick and sometimes they get shot down, but if an idea is easily executable there is no harm in trying something new and seeing what sort of creative impetus spawns from it.

In the previous post, I talked about ways in which contemporary classical production might evolve. Take some of these ideas or come up with your own and try them out. Maybe it won’t work, and that’s okay. I have no shortage of ideas that were left on the studio floor because they just didn’t work out, but there was no harm done. I take those experiences and learn from them. Sometimes I tweak the ideas until they finally do work, and other times I just move on entirely.

Trust yourself

Not only is it important to trust your team, but you must also trust yourself. If you’ve established a solid foundation of communication between all parties, you shouldn’t feel apprehensive about speaking up when something doesn’t sit right with you or you have an alternative idea. In a healthy collaborative setting, respect between all parties should be strong enough to hear out and work through any ideas presented. Ideas will never come to life if they aren’t presented in the first place.

As a performer, being in a studio and surrounded by studio equipment can sometimes be intimidating. We have years of experience as musicians, and all of these experiences are different from one another’s. Studio production teams are small and every person plays an integral role. Your knowledge and strengths make you a unique expert in your field. The engineer will handle the equipment, the producer will take care of organization and management, and the performers will know their instruments better than anyone else in the room. Know your field and know your limitations; you will have a team of people there to fill in any gaps and to support you and the project till the very end.