In my first post, I presented three vignettes—Bach’s job composing for the Weimar court, a village baker, and a playground designer—as ideal visions of the artist in community. In the community I imagine, artist and audience interact at a small, human scale around shared meaning that goes beyond the art itself. This allows art to grow organically within an environment that already needs it and therefore naturally fosters it and imbues it with meaning. In my second post, I argued that the internet is a good place for this kind of community—if we abandon social media as we know it, and create new, better platforms and processes for building community online.

Alternative social media platforms like Vero and MetaFilter offer something more human-centric and less dangerous than Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Likewise, email listservs and small-group communication like SMS group text chat can be useful, though often dysfunctional. But I have not found an option that fits what I need and what I believe others need, particularly as artists helping to build culture-sustaining communities. So in this post and the next one I will present two related experiments I am undertaking, both seeking in different ways to create high-quality, high-trust, human-centric, art-incubating communities on the internet.

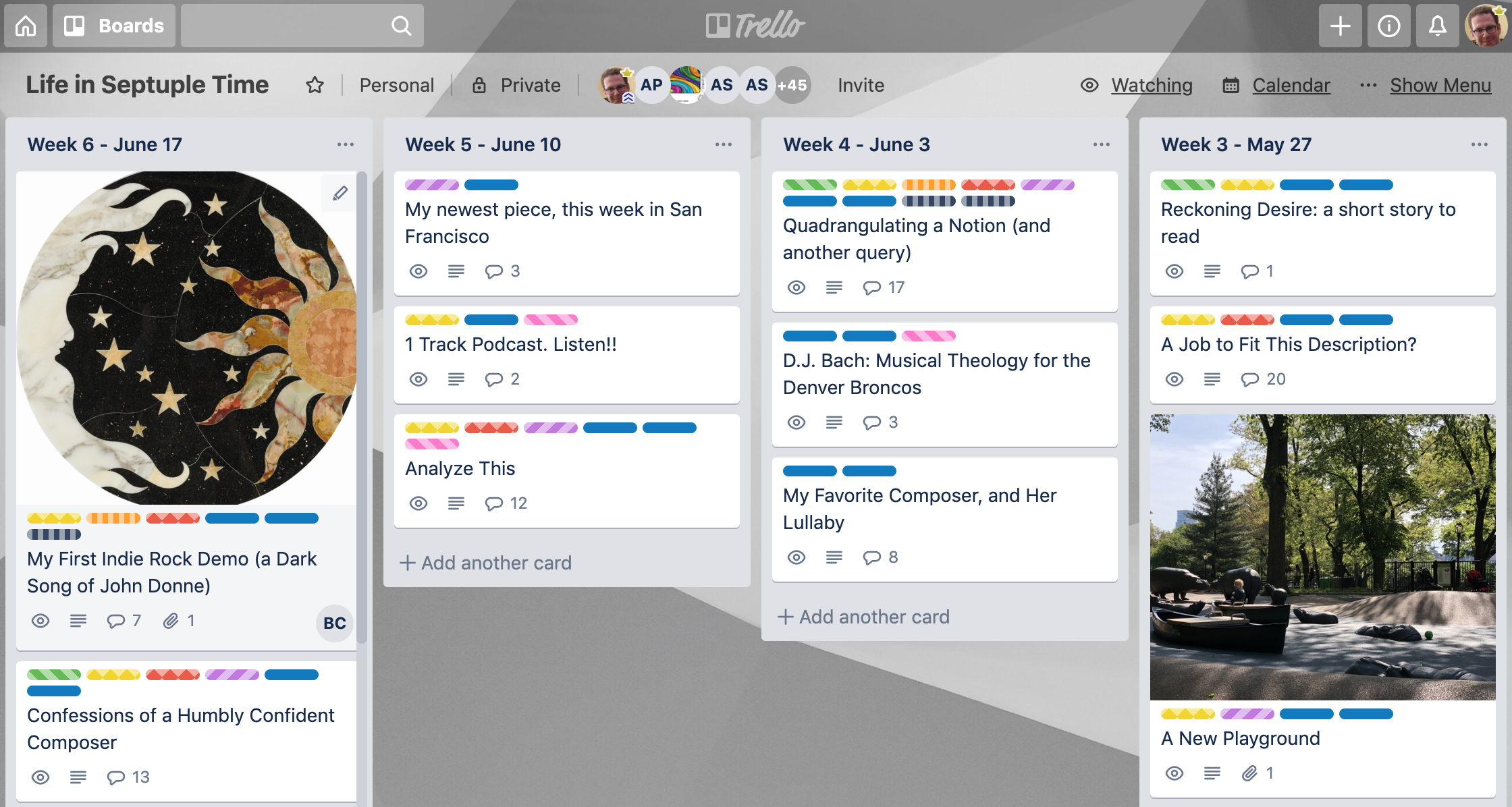

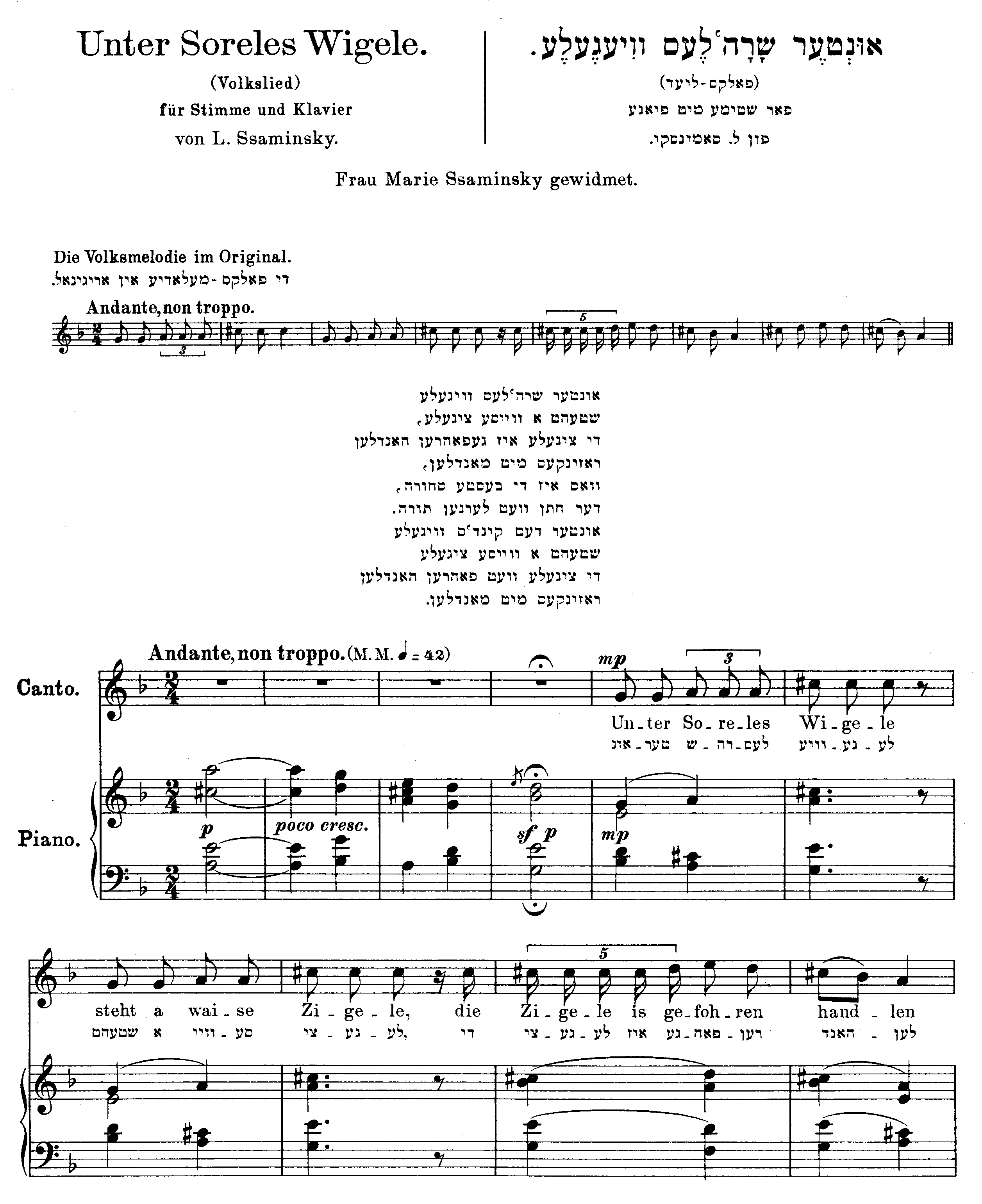

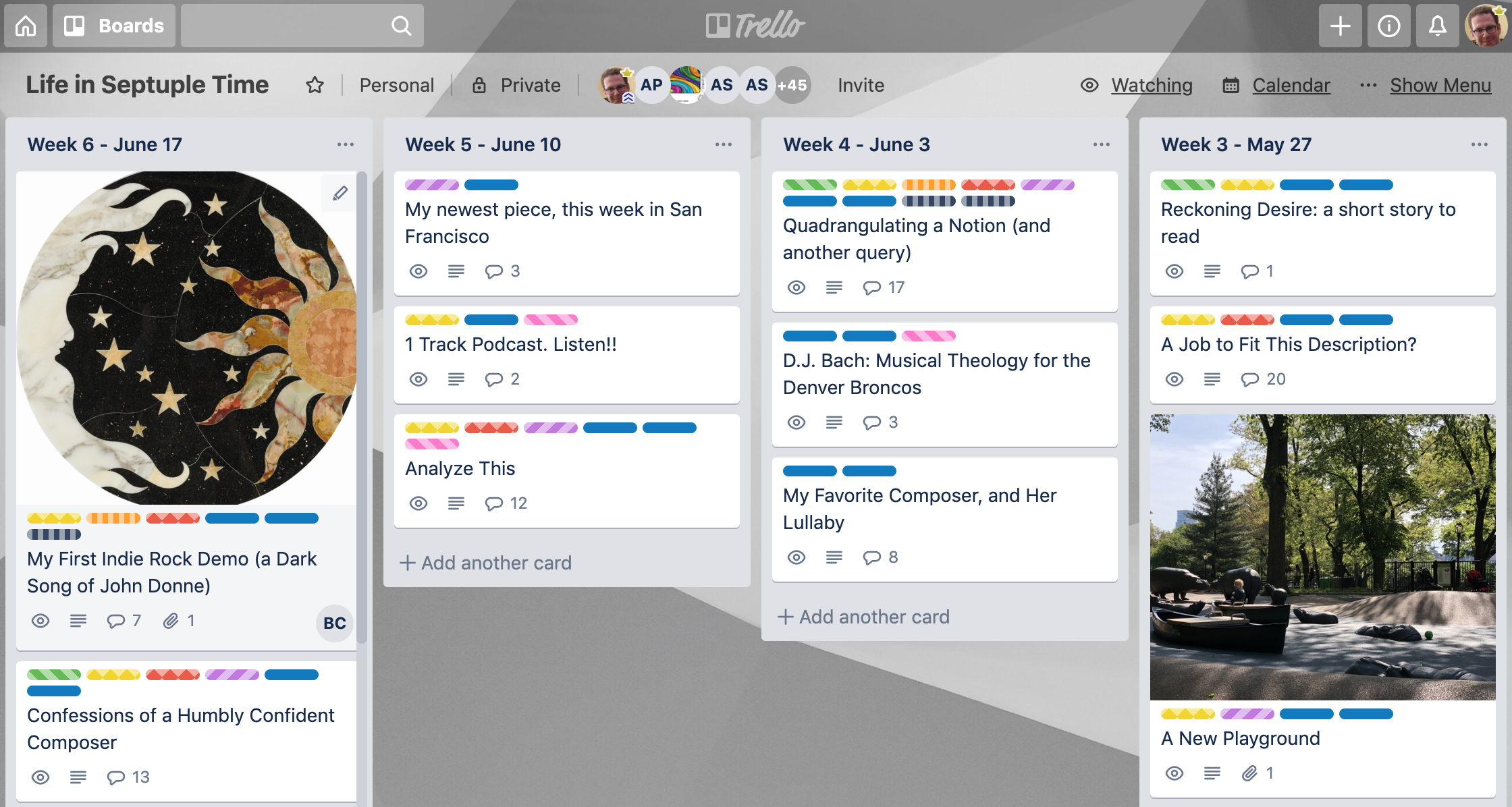

The first of these two initiatives, Life in Septuple Time, is a small-scale, private, peaceful social media space I am creating, centered around a thrice-weekly email I send to a limited list of friends and colleagues, with an option for group discussion using Trello software. This project, I hope, points to better ways we can do social media—in small groups with a high degree of trust, made by and for users with simple tools we control ourselves, without the advertising and algorithms that distort context and control, on our behalf, who sees what we share and how we understand each other.

Toward a Better Social Media

I felt sad to leave Facebook (though I don’t miss it).

In my previous post I was defiant about the evils of social media. But I felt sad to leave Facebook (though I don’t miss it). I have a lot of ideas and thoughts to share, and I love learning from other thoughtful people online. Also, I worried about my composerly life. Don’t we composers need to be present on social media these days? Isn’t this one of the vital ways we artists are supposed to reach our audiences? Despite these concerns, it felt good and necessary to leave the Big Social Media platforms. But rather than retreat to a world limited by physical place (as rich in meaning and connection as that can be), I resolved to seek another way to form community online—something better, something human-centric and free from coercion, something owned and operated entirely by human beings whose motives are connection, art, and meaning.

The other thing I abandoned was my good old professional email newsletter, another staple of the composerly life. I typically sent one every six months or so, to many friends and colleagues, with announcements about current projects and upcoming premieres. I received warm responses and it was a nice way to keep in touch with people occasionally. But it had begun to feel empty. It was a big list, including many people I barely knew, whom I had met only in passing. I knew that my newsletter was one of a multitude of similar ones that each person received. And whenever I announced a premiere, only a handful of those on my list lived anywhere nearby. I began to see that my newsletter failed to convey the ongoing story of my work and the things I cared about, the thinking process and context that fed and gave rise to the music I announced in each email, the things that give my work meaning. Without that, I felt more and more that these emails had little real impact, either for myself or my audience.

I didn’t like that my email newsletter was an opt-out communication.

And then there was the subtle sense of coercion I felt in my email newsletters. Though I would send each email with a note that the recipient was welcome to unsubscribe, and I was scrupulous in responding to those requests, the whole practice of publicizing my work this way began to feel like an arm-twist. Unsubscribing from a large company’s marketing email is not hard, but unsubscribing — having to take an action that says “I don’t want to hear from you” — from that nice guy you met at a conference… that’s harder. I didn’t like that my email newsletter was an opt-out communication. If a recipient wanted not to receive my email, I was asking them to confront me with their disinterest, or imagine themselves into a space where I was a faceless spammer. These kinds of emotional and interpersonal gymnastics are not good for our souls.

So with Big Social Media and my email newsletter gone, what in the world was I going to do, as a composer who wants to share his work with others — and composing aside, as a person who wants to interact and share with friends spread far and wide? In my search for alternatives, I was inspired by the model of daily email blogs like Composers Datebook and Seth Godin’s blog. These emails arrive first thing every single day, and each is very short. It’s a format that works well for me as a reader; these are the newsletters I tend to read and remember, the ones I move to the hallowed “Primary” tab in my Gmail inbox. Another trend and model that has been in my mind is the move many people are making away from large-scale social media and toward private, small-group interaction via group text chat, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and similar. (Facebook is on-trend in planning to move its design toward private, small-group interaction. That would be great if their entire business model were not so harmful. I’ll be staying away.)

As I planned this new project, I had three goals:

First, I wanted my group of recipients to be small. I was intrigued by Seth Godin’s concept of seeking the “minimum viable audience.” Instead of trying to reach as many people as possible, however superficially, I wanted to seek a smaller group, for a greater chance of connecting deeply. This feels like the opposite of the goals that guided my old efforts.

Many platforms tend to seek the largest number of readers. I wanted fewer.

Second, I wanted the project to be private, with no public web presence and no possibility of popping up on a web search. Again, this is the opposite of the goals of a traditional blog, with its public URL, seeking to reach as many readers as it can, to be findable in as many ways as possible. Writing platforms like Medium or Substack tend to seek the largest number of readers. I wanted fewer.

Third, it was important to minimize coercion as much as possible, to proceed with the fullest attainable permission and active acceptance of those who participated. Instead of showing up at someone’s email inbox with my composer party and saying, “Please ignore me or throw me out if you’re not interested,” I would start by assuming disinterest and then ask people to opt in. This would be a party held at my house, with an invite and RSVP. “Let me know if you want to come, and if I don’t hear from you, you need not worry about my party descending on your mental space.” Of course, any invitation from one human to another might inherently carry a hint of obligation, but I would take pains to make clear that this was truly at-will and optional.

My Experimental Solution

With all that in my mind, I sat down in early May and made a list of everyone I knew, and set about narrowing it down. I thought about my relationship with each person and the kinds of things I wanted to share. I tried not to ask myself the traditional questions a composer might in trying to publicize his work. Instead, I asked a human question (but one that has deep impact on art-making): How personal and vulnerable do I feel I can be with this person? At the end of this painstaking process I had only forty percent of the original list.

I sent that much smaller group an email invitation. I told them I was leaving social media, where many of them followed my posts, and ending my old email newsletter that many of them had received. I invited them to my new email series, saying that I would send short emails three times a week, and that if they wanted to join me they would have to actively opt in by replying to say “yes.”

I also shared some of the themes and interests I planned to discuss in my emails, including:

- How the modes of communication we use drive what we think and do, as much as the content of our communication.

- How the technology we use (any tool) affects the meaning of our creative work in tricky ways.

- What is art for? No seriously, what is it for?

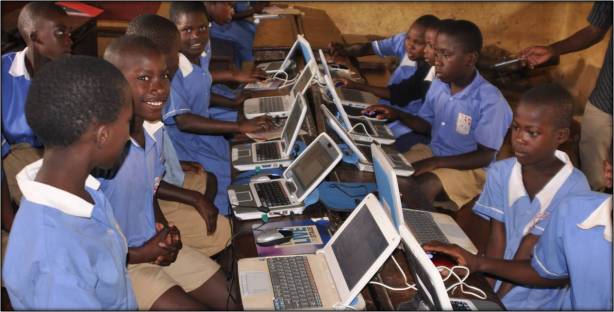

- Democratizing creative work: whys and hows (drawing from my composition teaching).

- Creating useful things for other people, and witnessing them being used, is a core human need. When not met, it can cause deep pain.

- Is it possible for an idea, a person, or a group to achieve broad cultural impact by being nice, by truly and completely avoiding the denigration of some other idea, person, or group?

- Computers will never think like people, but as they get smarter they can serve us as powerful tools to help us in our human-style thinking and creativity.

In an email-averse world, I did not think many people would want three emails each week, even short ones. But people said “yes!” And in much bigger numbers than I had expected — over half of those I had invited accepted my invitation. It felt confirming to receive those “yeses,” and because I had already narrowed the list to a small number, the ending total — about twenty percent of my starting list — did not feel like too many for my goal to stay small. I have chosen not to give the exact number, with its whiff of “how many social media followers do you have?” I think many people, including myself, are sensitive to how many social media connections other people have, and how many contacts in general. Knowing these numbers invites comparison and, potentially, feelings of envy or pity. When I have mentioned my rather average number of Facebook friends to others, sometimes they say “wow that’s a lot” a little wistfully — but just as often I have seen people with many times more than I have. These numbers feel meaningless because they depend on how one seeks and accepts friends; some people limit their list to people they know well, others keep a broader list. If someone else were to start an email series like mine, I would not want them to be comparing the numbers. Perhaps a larger or smaller number suits them. What is important to me in this project is the relationship I have with each person, and the kind of communication and community I want to foster.

Those who opted out are just as vital to the project as those who opted in.

It’s also important that those who opted out are just as vital to the project as those who opted in. When someone chose not to participate, I was a little sad. (I’m only human.) But I was also glad because it meant, to me, that my plan was working, that the trust was strengthened. If there were a sense of obligation or coercion beyond my initial invitation, it would change what I chose to share, the way I could talk to people, and the way they would hear me, even what they would hear. So I am deeply grateful to my opt-outs. (Of course, the party continues and they are always warmly invited to drop by.)

Perhaps the best part of the experience, so far, is that many people have told me that they are not only interested in reading my email content, they are also interested in the project as a project. They see that it is an experiment in communication and they want to witness it and find out how it feels to be part of it. Many have told me that they would love to do something similar, to share their own thoughts and work with their own group. Already, a good friend who is on my list has begun a similar email series with the same opt-in “yes” requirement. The single proudest moment so far was when he cited my email series, in the invitation he sent, as part of his inspiration for starting his own. The more who do so—the more my experiment invites others to share their honest and vulnerable selves with trusted others—the happier I’ll be.

If it Ain’t Got that Swing… Life in Septuple Time

One more important element: I wanted my project to have an interesting rhythm and a steady beat. I have talked a lot here about social relationships and communication dynamics. But I am a composer, and I know how important rhythm is to our experience of the world. This is not just for fun (though it is fun, I think) — it’s important because of the way it affects my readers’ experience of my emails. If each email is predictable, if you can tap your foot to them, then each encounter feels calmer and more welcome, less of an interruption. Because everyone involved—the whole ensemble—can feel the beat, knows when it will land.

The daily email blog model, sending a short email every single day, felt too monotonous (a 365/4 time signature?), and I thought it would be too much to handle both for me and my readers. So I decided it should go out every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, first thing in the morning always at the same time, 6am. I sent this to those on my list:

MWF makes the schedule easy to remember, and I like the spiky rhythm it gives to our 7-day week: 2 days, 2 days, 3 days; 7/8 time, two short beats and then a long, count it out loud 1-2, 1-2, 1-2-3, easy breezy like this …Dave Brubeck’s Unsquare Dance.

We already live life in septuple time, week by week. I wish every week were as fun as that Dave Brubeck song, and I hope my emails will add a gentle off-kilter beat to your weeks.

Let’s call this project: Life in Septuple Time.

Since starting the series almost three months ago I have kept up the MWF rhythm every week, sharing ideas on the themes I mentioned above. Topics range from geometric cuts I made in a slice of watermelon, to dilemmas I struggle with, to announcements of the latest premieres of my music. The people on my list respond to me individually by email to share related ideas, to offer their opinions or reactions to what I shared. It’s like a private blog with active commenting.

Since starting the series almost three months ago I have kept up the MWF rhythm every week.

With these guiding elements working together, my hopes for this project have been fulfilled so far. It’s so much better than anything I experienced on social media or with my old email newsletter. I reach people now. They read what I write. They might skip a day or a week, and that’s fine. What matters is that I have their permission and their attention. My community learns about me as an artist, and I learn about them — their lives, their needs, and what concerns they want our shared art to address. I can weave an ongoing story they can follow, make their own sense of, and respond to. It feels analogous to what I do as a composer, a sort of ongoing composition-in-email (in 7/8 time of course), which in turn fosters my musical composition. (I still announce my premieres and publications.)

Trello as Private Social Media Platform

As I knew I would, I soon began to crave discussion not just between me and each individual, but between these wonderful people I had gathered. I wanted group interaction and sharing, a sort of… what shall we call it… a media that is social. A better social media, without the intermediaries of advertisers and algorithms controlling who sees what. (It might seem a bit odd, because it’s a social media centered around me. I ask my list to suggest topics for me to write about, but mostly they have been happy for me to share my thoughts as I please).

I don’t know how many people silently visit or when, and I don’t seek to find out.

And so, I looked for an online platform that felt peaceful, where people could comment but where the layout and pace could be measured and relaxed. I settled on Trello, the popular project-management software. I invited those on my list to join me on the Life in Septuple Time Trello board, and about a quarter of them have joined (the rest opt to participate by email only). It has become a lovely private online community, by and for its participants, hosted by a human (me), no data gathering or algorithms needed. I don’t know how many people silently visit or when, and I don’t seek to find out. When someone comments, then I know they’re there — not because I gathered data on them and encroached on their personhood, but because they exercised their humanity and free will to let me know they are present.

Our Trello board for Life in Septuple Time looks like this. Each card is one of my MWF emails. People comment in the cards and chat with each other. I use colored labels to track the themes (mentioned earlier) that we cover in each discussion card.

Some Questions

What does success look like for a project like this? Does such a thing scale up? Can it? Should it? If I am not seeking a larger audience, where does this go next? What are the goals?

If I get to know a thoughtful person who wants to join, I am glad to add them. (The point is trust, not smallness for its own sake.) But my main goal, my hope, is that more people will start their own projects like this, tailored to suit them. It doesn’t have to be done the way I’ve done it, for example the MWF rhythm might be too frequent, or not frequent enough. The friend I mentioned who has started his own email list is doing it on a once-weekly basis, not thrice weekly like mine.

There are many friends whose thoughts I would gladly receive in a similar mode. I dream of a series of Trello boards (or some other suitable platform) each containing the universe of one friend’s thoughts and interests which I could follow and visit. Sounds like Facebook? On the surface, perhaps. But fundamentally, it’s a different orientation and feeling. I keep bugging my list, encouraging others to start their own series like this. I’ll join them all.

Piling in is what cheapens the entire enterprise of Facebook and the other mainstream platforms.

Would there eventually be too many to keep up with? Maybe, but unlikely. Many of the people on my list have told me they don’t want to broadcast in this way, that being in the audience feels just fine. Keeping the series going, keeping the beat steady, is much more involved than posting on Facebook, more like running a blog. It’s a commitment. Others have told me they are interested in trying something similar, but they don’t have the time. So maybe it could be more like Facebook, where everyone piles in and competes for attention! Let’s fire up some algorithms to drive engagement! Ha. To me, that piling in is what cheapens the entire enterprise of Facebook and the other mainstream platforms. So, asking for real: How could everyone who wants to do so produce such a thing, all those whose lives are too busy or otherwise impeded? And if there got to be many of these invitations, how could everyone keep up with everyone? I don’t have an answer for this yet, but I’m working on it and I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

One more question for now: How will I become the World-Famous Composer I clearly deserve to be, if I stop broadcasting my work to lots of people? How will anyone know about my work if I ditch big email newsletters and avoid all mainstream social media platforms? If I instead share my thoughts privately with only a few people? Isn’t that just me, um, having friends? What happens to my Big Composer Dream?!? I hope you can hear the wink in my questions.

Fame starts small if it starts at all.

I have answers, and without the wink. First, I have my good old composerly website. It maintains a professional public presence, and people use it to purchase music for performance. Much more important, however, I’ve learned—slowly—that fame starts small if it starts at all. If my music inspires a few people and they pass it on to someone else, then perhaps someday down the line I might gain influence and reputation. But that secondary stage is… secondary. I haven’t done the first part yet, until now. I always thought I was doing it, but I wasn’t. And it’s already giving me at least 80% of the joy that fame would offer, possibly 101%. Because the joy lies in connecting with others in a genuine way.

The “Manhattan Solstice,” when the sunset aligns with Manhattan’s street grid. Viewed from West 79th Street & Columbus Avenue. (Photo by Robinson McClellan)

Not Far Enough Yet

So. My email series Life in Septuple Time tackles some of the problems with online interaction that I feel. But it’s still social media, in the sense that it primarily involves one person broadcasting outward to a group. I hope I am doing it in a healthier, more positive way than it was possible to do using Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. But ultimately I want more than broadcast: I want community. That’s why I added the Trello board as a miniature private social media space for those on my email list. It’s great, and I will keep doing it, but it’s still just broadcast, and it’s only Phase One of the larger plan I have in mind.

Ultimately I want more than broadcast: I want community.

Here’s what I ultimately crave: small, co-equal groups that include art-markers serving those who are happy to be their audience, a group gathered around shared meaning bigger than the art itself, where learning and art can grow organically. Next target: reshaping the broadcast structure of social media to create something quite different. This brings us to the second initiative I am co-creating, Terrarium, which I’ll talk about it in the next post. Stay tuned!