Forgive me if I begin this look back at twenty years of NewMusicBox and its times by opening a different, older, but resolutely print magazine. In October 2000, about 18 months after NMBx’s founding, The Wire, the UK-based magazine for new and exploratory music, reached a milestone of its own: issue number 200. It marked the occasion with a directory of 200 “essential websites”: sites for record labels, venues, artists, discussion groups, and more. Nearly two decades later, the idea of trying to write down any sort of meaningful index to the web seems extraordinarily quaint; but at the start of the century, before Google transformed how we think about information, such things were not uncommon. Back then—and I’m just about old enough to remember this—it still felt as though if you put in a few days’ work, you could pretty much get a complete grasp of the web (or at least of that slice of it that met your interests).

Within The Wire’s directory, among a collection of links to 18 “zines,” sits NewMusicBox. Here’s Christoph Cox’s blurb:

Run by the American Music Center, an institution founded in 1942 [sic] “to foster and encourage the composition of contemporary music and to promote its production, publication, distribution and performance in every way possible,” NewMusicBox’s monthly bulletins do this admirably, and, with recent issues exploring topics as various as the relationship between alternative rock and contemporary classical, the funding of new composition, and the world of microtonality, regular visits are worthwhile.

NMBx’s presence on this list isn’t surprising. (Although I hadn’t looked at this issue of The Wire for many years myself, I was confident the site would be in there.) The online magazine of the AMC (and later New Music USA) has always been close to the forefront in online publishing. What is surprising—and just as telling—is that aside from a few websites devoted to individual composers (Chris Villars’ outstanding Morton Feldman resource; Eddie Kohler’s hyperlinked collection of John Cage stories, Indeterminacy; Karlheinz Stockhausen’s homepage-slash-CD store-slash-narrative control center stockhausen.org), almost no other sites in The Wire’s catalogue are devoted to contemporary classical music or modern composition. The sole major exception is IRCAM, whose pioneering, well-funded, and monumental presence (especially through its ever-expanding BRAHMS resource for new music documentation) gives an indication of the level NMBx was working at to have achieved so much so early on.

[banneradvert]

Although NMBx was at the forefront of online resources in 1999, the idea of an online publication for contemporary American music had been circulating at the AMC for some time. A long time, in fact. In 1984—just two years after the standardization of the TCP/IP protocol on which the internet is built, and when the web was still called ARPANET—the AMC’s long-range planning committee wrote, “The American Music Center will make every effort to become fully computerized and to develop a computer network among organizations concerned with contemporary music nationwide.”[i] This seems like an almost supernatural level of foresight for an organization that was still at that time based around its library of paper scores. That is, until one recalls the number of composers, especially of electronic music, who were themselves at the forefront of computer technology. One of these was Morton Subotnick, a member of the AMC board and one of new music’s earliest of early adopters. Deborah Steinglass, currently New Music USA’s interim CEO, but back then AMC’s Director of American Music Week (and soon to become its Development Director), recalls a meeting in 1989—the same year that Tim Berners-Lee published his proposal for a world wide web—in which Subotnick introduced the potential of computer networks for documenting and sharing information to the board, whose members were astonished and incredulous.[ii]

From its beginnings, NMBx was about making composers heard.

Yet they were moved to take it seriously. Carl Stone, another composer-board member who was involved from an early stage, reports that early models were an ASCII-based Usenet or bulletin board-type system that would allow users to exchange and distribute information nationwide.[iii] This idea evolved quickly, and ambitiously. A strategic plan drawn up in 1992 and submitted in January 1993 states that during 1994, the Center would “create an online magazine with new music essays, articles, editorials, reviews, and discussion areas for professionals and the general public.” Alongside Stone and Subotnick, the early drivers of this interest in technological innovation included fellow board members John Luther Adams, Randall Davidson, Ray Gallon, Eleanor Hovda, Larry Larson, and Pauline Oliveros.

This is not to say that everyone at the AMC was an early adopter; Stone says that one of his main tasks was “to keep driving the idea of an online service forward. While it might seem obvious today, there was significant resistance to an online service in some quarters. Some people felt it would be dehumanizing, expensive. They couldn’t see the coming ubiquity of computers in our daily life.” A key role in maintaining this drive, Steinglass tells me, was played by the AMC’s Executive Director Nancy Clarke. Clarke, a music graduate from Brown University, had worked as a music program specialist at the National Endowment for the Arts before coming to the AMC in 1983. According to Steinglass, Clarke was very interested in technology and was sympathetic to the predictions of Subotnick and others. It was she as much as anyone who pushed for and implemented an online presence for the AMC.

The fruit of these discussions (and several successful funding bids written by Steinglass) was the launch of amc.net in the first half of 1995: the same year as online game-changers such as eBay and Amazon, but months before either. In fact, the AMC’s website (designed by Jeff Harrington) proved to be one of the world’s first for a non-profit service organization, a testament to the vision and ambition of Clarke, Stone, Subotnick, and the rest of the AMC board. By June 12, according to a letter from Clarke to the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust (one of the site’s funders), it was already receiving a respectable 20,000 hits a month.

Yet the goal of a web magazine devoted to contemporary American music—meaning all sorts of non-commercial music, from jazz to experimental, as well as concert music—remained incomplete. In that same June letter, Clarke lists the services amc.net was providing: they include a catalogue of scores held in the AMC’s library; a compendium of creative opportunities (updated daily); listings of jazz managers and record companies; a forthcoming database of composers, scores, performers, and organizations; and that mid-’90s online ubiquity, the guestbook. But no mention of a magazine.

The idea was reinvigorated in 1997. Richard Kessler arrived as the AMC’s new executive director and amplified the need for the AMC—and indeed other music information centers like it—to do more than offer library catalogs and opportunity listings. “We’re supposed to be about advocacy,” is how he describes his thoughts at that time. “And not just [for] composers, but also performers and publishers and the affiliated industry.”[iv] To achieve this, Kessler reasoned, the AMC needed to switch its attention away from its score library and towards ways to give a voice to composers across the spectrum, particularly those working at the margins of the established scene. “There are composers out there who, if they’re not published, people don’t know who they are or what they’re doing,” he says.

Planning documents and funding applications produced shortly after Kessler’s arrival in July 1997 discuss the development of “a twice-monthly web column” that would provide “first person” perspectives on American music by experts and practitioners within the field.[v] At this stage an online magazine does not seem to have been in anyone’s mind, although it was suggested that these columns would be supported by chat forums, links, and other materials. Kessler was clear about what he wanted this publication to do, whatever form it might finally take: it should give “a palpable, well-known voice to the American concert composer, broadly writ. I also wanted it to affirm the existence of those artists. Can you play a part in ensuring that those artists will exist in that [online] space? Not only for people to discover them, but also for the artists themselves to feel like they do exist.”[vi]

By late spring 1998, the “American Music: In the First Person” proposal had evolved into an idea for a multi-part online newsletter. Planning documents from May of that year introduce the idea of a monthly internet-based publication “serving as a communications and media vehicle for new American music.”[vii] These documents are aimed more generally at creating an “information and support center for the 21st century,” but the presence of the magazine is regarded as the “linchpin” in that new program.

After this, things moved quickly. On July 1, a conversation between Kessler and Steve Reich was published on the AMC’s website. This was the first of a series of interviews entitled “Music in the First Person” (and which still continue under the title of “Cover”): it is interesting to note how the “first person” of the title shifted from the author of a critical essay or column, as proposed in May, to the (almost always a composer) subject of an interview. In the same month, Frank J. Oteri was approached—and interviewed—for the job of editor and publisher of the planned magazine, a position he took up in November. NewMusicBox published for the first time the following year, on May 1, 1999, featuring an extended interview with Bang on a Can, an extensive history of composer-led ensembles in America written by Ken Smith, “interactive forums,” news round-ups, and information on recent CD releases.

NMBx has grown up alongside the internet itself, and often been close to its newest developments.

NMBx has grown up alongside the internet itself, and often been close to its newest developments. The original “Music in the First Person” interviews that began in 1998 were published with audio excerpts as well as text—a heavy load for dial-up era online access. A year later, the April 1, 2000, interview with Meredith Monk introduced video for the first time. And on November 22, 2000, NMBx released its first concert webcast(!). This was a recording, made by then-Associate Editor Jenny Undercofler a week before, but the first live webcast came only a little later, on January 26, 2001—almost eight years before the Berlin Philharmonic’s pioneering Digital Concert Hall. The innovations continued: with its regularly updated content, comments boxes, and obsessive (and often self-referential) hyperlinking, NMBx was a blog almost before such things existed, and certainly long before anyone else was blogging about contemporary concert music. Composer and journalist Kyle Gann and I started our respective blogs in August 2003, although it was a little while before I wrote my first post about new music; Robert Gable beat us both by a month with his aworks blog. In fact, Gable introduced our particular blogospheric niche to the wider world in a post he wrote for NMBx in October, 2004; within weeks, Alex Ross had joined the fun, and the rest is …

Many early innovations were brought to the table by Kessler, who saw potential in webcasts, discussion groups, and more, but this is not to say that the early plans for NMBx didn’t also feature some cute throwbacks. Among them, plans for link exchanges (links to your work having a great deal of currency back then), and elaborate content-sharing schemes with external providers before YouTube, Spotify, and Soundcloud embedding made such things meaningless.

From its beginnings, NMBx (and the wider organization of AMC) was about making composers heard. In the late 1990s what this meant and how it might be achieved was still seen through a relatively traditional lens. One funding application mentions that in spite of recent advances in technology and society, “many of the challenges that faced the field decades ago remain more or less unchanged.” It goes on to list them:

- the need for composers to identify and secure steady employment

- the need to educate audiences and counter narrow or negative perceptions of new music

- the need to instill institutional confidence about the importance of new music—whether from orchestras, opera companies, publishers, media, or record companies

- the need to encourage repeat performances of new music

- the need to secure media coverage of new music[viii]

At this stage, the internet was still regarded by many as a tool for amplifying or augmenting existing models of publication. The editors had to field questions about whether the magazine would ever be “successful” enough to launch a paper version.

At this stage, the internet was still regarded by many as a tool for amplifying or augmenting existing models of publication and information sharing. In the same year as NMBx was launched, I joined the New Grove Dictionary of Music as a junior editor and ended up part of the team that oversaw Grove’s transition from 30-volume book to what was then one of the world’s largest online reference works. For several years after 1999, we were focused on making a website that was as much like the book as possible. (This was harder than you would imagine: Grove’s exhaustive use of diacriticals, for example, made even a basic search engine a far from simple task.) As far as maximizing the opportunities of the web went, this extended largely to adding sound files (that were directly analogous to the existing, printed music examples) and hyperlinks (analogous to the existing, printed bibliographies), along with editing and adding to the existing content on a quarterly basis.[ix] My experiences at Grove were echoed in NMBx’s office. The editors had to field questions about whether the magazine would ever be “successful” enough to launch a paper version; one planning document (perhaps trying to assuage the fears of the screen-wary) reassures that “anyone who wishes to download a copy of the magazine for printing and reading at a later date will be able to do so free of charge.”[x]

Just a few years into the new century, however, things began to change in ways that hadn’t been anticipated, even by those at the forefront of technological application. Blogging in particular had revealed two powerful and unexpected abilities of the web: to complicate our understanding of truth and to amplify the functions of style, personality, and connections within the new media economy. In the second half of the decade, these were supercharged by the arrival of social media.

This changed what it meant to be heard. Continuing to exist as a composer was no longer about accessing authorial gatekeepers—becoming audible through major performances, broadcasts, and publishing contracts—but about telling personal stories of identity and representation, and about shining a light outside of the mainstream. These changes were anticipated early on at NMBx—the forum discussions from that very first “Bang on a Can” issue centered on the subject of audience engagement—and continue to be reflected in its features.

Continuing to exist as a composer was no longer about accessing authorial gatekeepers but about telling personal stories of identity and representation.

Oteri and Molly Sheridan, who replaced Undercofler as associate editor in 2001, have guided NMBx to its 20th birthday—a remarkable continuity of leadership for any publication, online or off! Along the way, they have directed many stages in its evolution—including several site redesigns—and launched many innovations. The major facelift came in 2006, and with it a move from monthly “issues” to a rolling schedule of articles and blog posts that was more in line with the stream-based style of the growing web. By now, NMBx was essential online reading for anyone interested in contemporary American music, and hot on the heels of this redesign came another enduring innovation: the launch of Counterstream Radio in March 2007. Advertised on its press release as “Broadcasting the Music Commercial Radio Tried to Hide from You,” Counterstream caught a mid-noughties trend for online radio stations, but has endured better than some others.

Sheridan at work on Counterstream Radio

Yet although Frank (currently composer advocate for New Music USA, in addition to his NMBx work) and Molly (now director of content for the organization more broadly) have always had a strong idea of the best direction for NMBx, the debates in its pages are often sparked by practitioners themselves. (From the beginning, readers were invited to participate in forum discussions around a wide range of field issues or tied directly to individual posts; some of my strongest early memories of NMBx are of the lively conversations that would take place below the line.) To that extent, the site remains focused on what composers want to read; and judging by some of the recurring themes in NMBx’s 20-year archive of articles and blog posts, what composers want to read seems to be: how to get your work heard; how to create (even write for!) an audience; and how to engage with modernity and/or technology.

Even more importantly, there have also been, from the start, debates about representation. Concert music has been slow to confront its problem with race, for example, but it has been part of the conversation at NMBx for years: perhaps appropriately, since as changes in representation have come, one must hope that new music will lead them. Musicologist Douglas Shadle’s recent article on “Florence B. Price in the #Blacklivesmatter Era” is a valuable contribution, but even more pertinent has been the voice NMBx has given to living composers of color—from the early interview with Tania Léon in August 1999 through to the most recent of all featuring Hannibal Lokumbe, with many opinion pieces like Anthony Greene’s “What the Optics of New Music Say to Black Composers” along the way.

NMBx has been led by the compositional community, but it has been able to reflect that community’s concerns as they have played out in the wider world as well.

In areas like these, NMBx has been led by the compositional community, but it has been able to reflect that community’s concerns as they have played out in the wider world as well. As someone involved in the world of new music not as a creator but as a critic, observer, and occasional programmer, features like these are immensely valuable to keeping an eye on my own privilege, and to pushing me to open up the margins of my own understanding. Greene’s observation that “new music has done very little to change the expected optics of classical music, which is why new music’s identity problem is what it is today” is a powerful caution against complacency.

To take another example of those optics, the subject of gender representation and the problems faced by women in the contemporary music world were first addressed pre-NMBx, beginning with Richard Kessler’s February 1999 interview with Libby Larsen. They have remained in the foreground ever since, suggesting that the question remains current, but very much unresolved. A search for “gender” in the NMBx archive brings up almost 200 items, yet this isn’t even everything—it leaves out Rob Deemer’s widely read 2012 list of women composers, for example. (Forty-one items have also been tagged with the word “diversity,” though this list is not a free-text search, and only goes back to 2012.) The debates at NMBx wove in and out of conversations in the wider world. In 2002, guest editor Lara Pellegrinelli—who had recently written for the Village Voice about the lack of women musicians involved in Jazz at Lincoln Center—published a series of posts by women musicians, each headed “How does gender affect your music?” (Jamie Baum’s response: “When asked if gender has had an influence on my compositions, my reaction was of surprise—surprise that I hadn’t been asked that question before, not in 20 years of performing.”) Blogger Lisa Hirsch’s extended article of 2008, “Lend Me a Pick Ax: The Slow Dismantling of the Compositional Gender Divide,” added essential concert and interview data to the debate, highlighting the difference between post-feminist fantasy and harsh reality; and composer Emily Doolittle, with Neil Banas, offered an interactive model to highlight “The Long-term Effects of Gender Discriminatory Programming.” A widely derided column in the conservative British magazine The Spectator of 2015 (“There’s a Good Reason Why There Are No Great Female Composers”) prompted a suitably damning response from blogger Emily E. Hogstad (“Five Takeways from the Conversation on Female Composers”) that deftly drew together several moments across both new and historical music, and in the wake of 2012’s International Women’s Day composer Amy Beth Kirsten enriched the discussion with a call for the death of the “woman composer.” This last article attracted more than 100 comments and extensive debate, but the one that attracted so much interest it briefly crashed NMBx was Ellen McSweeney’s “The Power List: Why Women Aren’t Equals in New Music Leadership and Innovation,” a nuanced response to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In and its applicability to the world of new music. Tying questions of both race and gender together was Elizabeth A. Baker’s remarkable intersectional cry, “Ain’t I a Woman Too,” from August last year.

Perhaps most indicative of all was Alex Temple’s 2013 piece, “I’m a Trans Composer. What the Hell Does That Mean?” Temple’s article (originally published on her own website) is explicitly a follow-up to other NMBx contributions on gender, two of which are mentioned in its opening paragraph. It adds layers of nuance to the debate, both around the question of male/female binarism, as well as the question of whether compositional style can be gendered. No, says Temple to this latter, but:

I have noticed that certain specific attitudes toward music seem to correlate with gender … While I don’t think of my work as specifically female, I do think of it as specifically genderqueer. Just as I often feel like I’m standing outside the world of gendered meanings, aware of them but never seeing them as inevitable natural facts like so many humans seem to do, I also tend to feel like I’m standing outside the world of artistic meanings.

In its combination of raw experience and careful self-reflection, Temple’s article is exemplary but not unique to NMBx; an equally honest and unmissable piece, this time on musico-racial identity, is Eugene Holley, Jr’s “My Bill Evans Problem.” For those of us—including me, I confess—who have found ourselves under-informed about trans issues, Temple’s article provided a welcome introduction: not only to the terms of that discussion, but also for its possible ramifications for artistic creativity and self-expression (articles published since, including Cas Martin’s “An Ode to Pride Month,” have added layers of their own).

The continuing presence of articles like these brings us back to the core purpose of NMBx as the AMC envisioned it back in 1997: to allow composers to feel like they exist. In 2019 that is not only a question of allowing composers to feel like they exist as composers, within the framework of institutional support and recognition, but as people, within the framework of a more humane, more complete understanding of what we are as a society. In recent years, one or two online publications have found ways to discuss difficult social questions within the context of contemporary music; it’s rarer still to see it done with the same level of peer-to-peer sharing of knowledge and experience. NMBx, built in the best days of the web, was there before them all.

-

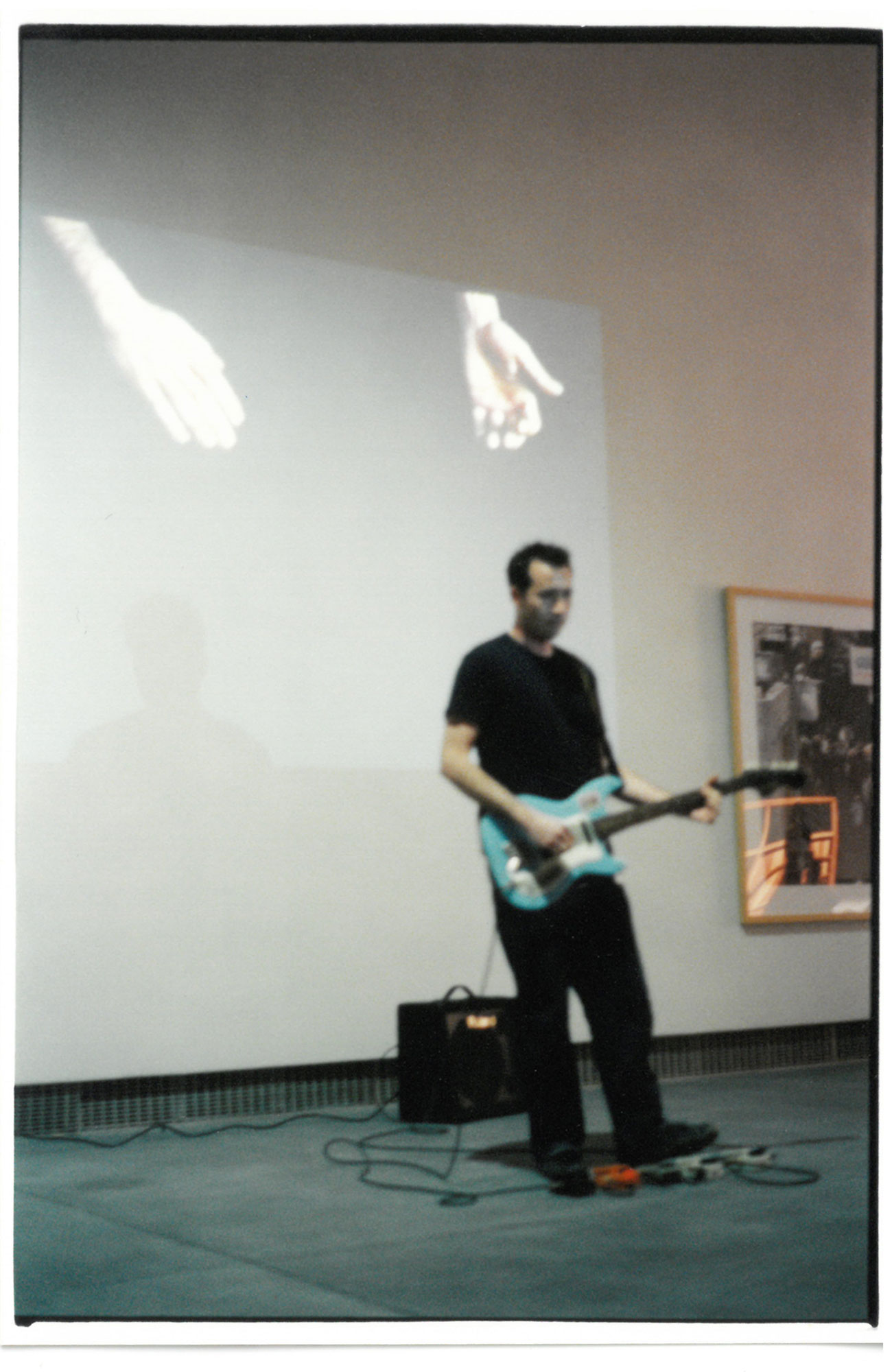

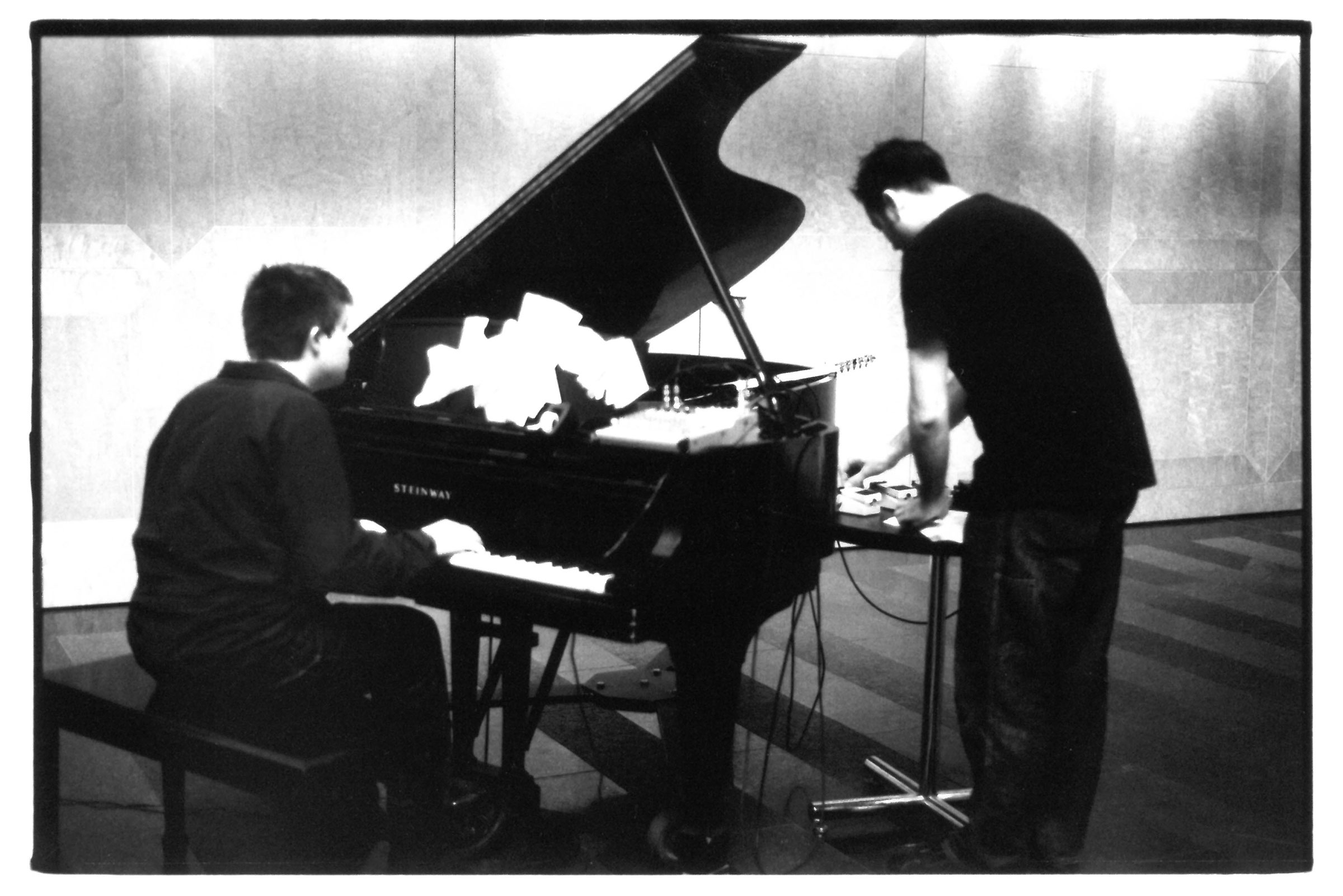

- Frank J. Oteri in conversation with composers Andy Akiho…

-

- …Daria Semegen…

-

- …Missy Mazzoli…

-

- …and André Previn. All photos by Molly Sheridan.

In the twenty or so years since we started to pay attention to it, the internet has concatenated every part of our private and public lives. Art, culture, sport, business, and gossip no longer appear separately, like supplements in our weekend newspapers, but together, on the same screen as dinner plans, memes, and conversations with our friends. Since the advent of Twitter, different things have become even more closely braided within the same scroll-stream, units differentiated only by the volume at which they declare themselves from our screens: #ClimateCatastrophe, #FiveJobsIHaveHad, #WorldPenguinDay read three hashtags in close proximity on my TweetDeck right now.

This is not altogether a bad thing. In the 1980s and ’90s, before this whole online thing really took off, musicologists and critics would fret about the disassociation of classical “art” music from life, and of musicology from society. Popular music was better at inserting itself into and complementing people’s lives. Film, literature, and theater were also good at it. Yet music, it was argued, was somehow still regarded in the abstract. It was partly in response to this that the scholarly movement that came to be known as New Musicology was born, having as its aim the study of music within its social context, music as a social creation. Today, music inhabits very much the same space as everything else in our lives (just as music is increasingly made out of the components of those lives). NMBx’s blogs and features, which place the day-to-day stories of actual new music composers at the center of the discussion, are a perfect reflection of this. The internet, with its indifferent reframing of everything as #content, has played no small role in this change in how we see the world. Few people talk of New Musicology now. Not because its premises were wrong, but because they have become standard practice. In this, as in so much else, NewMusicBox has long been ahead of the curve. Here’s to existing, always.

Thanks to Jeff Harrington, Richard Kessler, Debbie Steinglass, and Carl Stone for sharing with me their recollections and documentation of the early days of NMBx and amc.net.

[i] Quoted in American Music Center, 1992: “The Arts Forward Fund: Request for Proposal,” n.p. (“Proposal Summary”).

[ii] Deborah Steinglass, email to the author, April 5, 2019. According to Steinglass, Subotnick “also talked about the future of transportation, and how the US would have highways filled with electric vehicles none of us would actually have to drive.”

[iii] Carl Stone, email to the author, April 10, 2019.

[iv] Richard Kessler, Skype interview with the author, April 5, 2019.

[v] I am grateful to Richard Kessler for sharing these and other documents with me, and for permission to quote from them.

[vi] Kessler, Skype interview.

[vii] American Music Center, 1998: “An Information & Support Center for the 21st Century: An Action Plan.”

[viii] American Music Center, 2000: “A Proposal to the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation to Support an Online Information and Communications Infrastructure for New American Music,” page 10.

[ix] I am happy to report that since my time at Grove – or Oxford Music Online as it is now known – these ambitions have expanded greatly.

[x] American Music Center, “An Information & Support Center for the 21st Century,” page 5.