“Mashups of the Mona Lisa” created by Dave Winer, via Flickr CC

The predominant ideology in composition today, across all genres, is rooted in pastiche. Most composers in the new music community aren’t consciously thinking about this, but we’re involved all the same. I mean, just look at the names: new complexity, neo-romanticism, post-minimalism—three of the broadest trends in contemporary music, all with echoes of pastiche baked right into their labels. Of course not everyone is writing “in the style of” or explicitly quoting other pieces, but the desire to build perceptible bridges between musical traditions is nearly universal.

And it’s not just in classical composition. Virtually all of the most celebrated new art of our time, across genres and disciplines, whether high art or populist entertainment, relies to some extent on pastiche. You will find a healthy serving of the stuff in everything from the music of Jennifer Higdon to Nico Muhly to Thomas Adès, not to mention Taylor Swift, the Star Wars movies, and the memes in your Facebook feed. Pastiche clearly strikes a chord with the cultural zeitgeist of the moment.

Now before we get any further, pastiche is a broad term and there’s certainly disagreement on what it should mean. I’m most interested in the sense of “appropriation designed to be recognizable.” That is the type of pastiche that has taken over art, with an emphasis on “recognizable.” Clearly artists have always taken ideas and materials from other sources—how could we not?—but never before have we so celebrated the attribution of those sources.

In previous decades, society’s archetype of a great artist was the solitary genius who creates strikingly original work (supposedly) out of thin air. To expose one’s sources was frowned upon, because it gave the lie to the myth. Today, society seems to have the exact opposite set of priorities: art that borrows liberally and obviously from other sources generates the most praise.

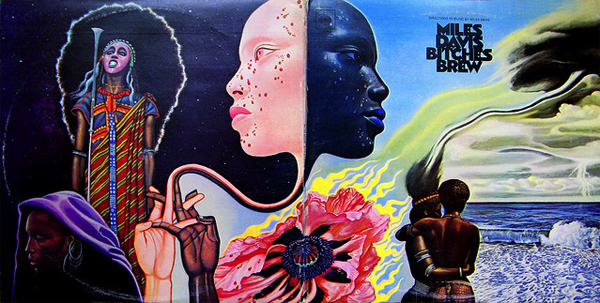

Image created by AK Rockefeller, via Flickr CC

A changing of the ideological guard

What we’re witnessing is essentially an ideological shift. Music critic and composer Kyle Gann got me thinking about this with the accidentally incendiary update he posted to his blog in late 2015. In it, he complains that young composers today produce nothing but tepid, middle-of-the-road work devoid of ideological backbone. It’s just “kids these days” nonsense, but he does manage to demonstrate just how far society’s priorities have mutated.

All artistic ideologies (or at least those that make an impact) arise as a response to the values of a society. Consider, for example, the rise of serialism (as a way of understanding music, not just as a compositional technique). Although today serialism is often associated with rigidity, its success stemmed from its flexibility, from the many ways it resonated with the concerns of Cold War-era composers. It was, among many things, a reaction against fascism, a reflection of democratic ideals, an outgrowth of 20th-century scientific optimism, and a way to professionalize music and bring it into academia.

During its heyday, serialism and its ideological relatives allowed composers to create music that harmonized with their views of the world and how they saw themselves within it. But the world is always changing, and the ideals of serialism eventually became disconnected from the concerns of a majority of composers. Slowly, gradually, other ways of understanding music took over in a messy, overlapping process that is hard to see in action but that becomes visible in hindsight.

It’s important not to oversimplify this narrative: serialism was never the only game in town; it was always one strand within the larger modernist project, which in turn faced competition first from traditionalist and neo-classical ideas, then from postmodern philosophies as well as paradigms arising from jazz, folk, rock, and other popular genres.

So just as we can’t pinpoint the exact moment that serialism lost its dominance in new music, or bebop in jazz, et cetera, et cetera, it’s hard to say exactly when pastiche became king (as a way of understanding art, not just as a technique). But king it is, and to an extent rarely seen for past ideologies. Its dominance holds true across an extremely wide swath of art making, from the most commercial Hollywood movie to the edgiest new music concert.

On the makings of a blockbuster

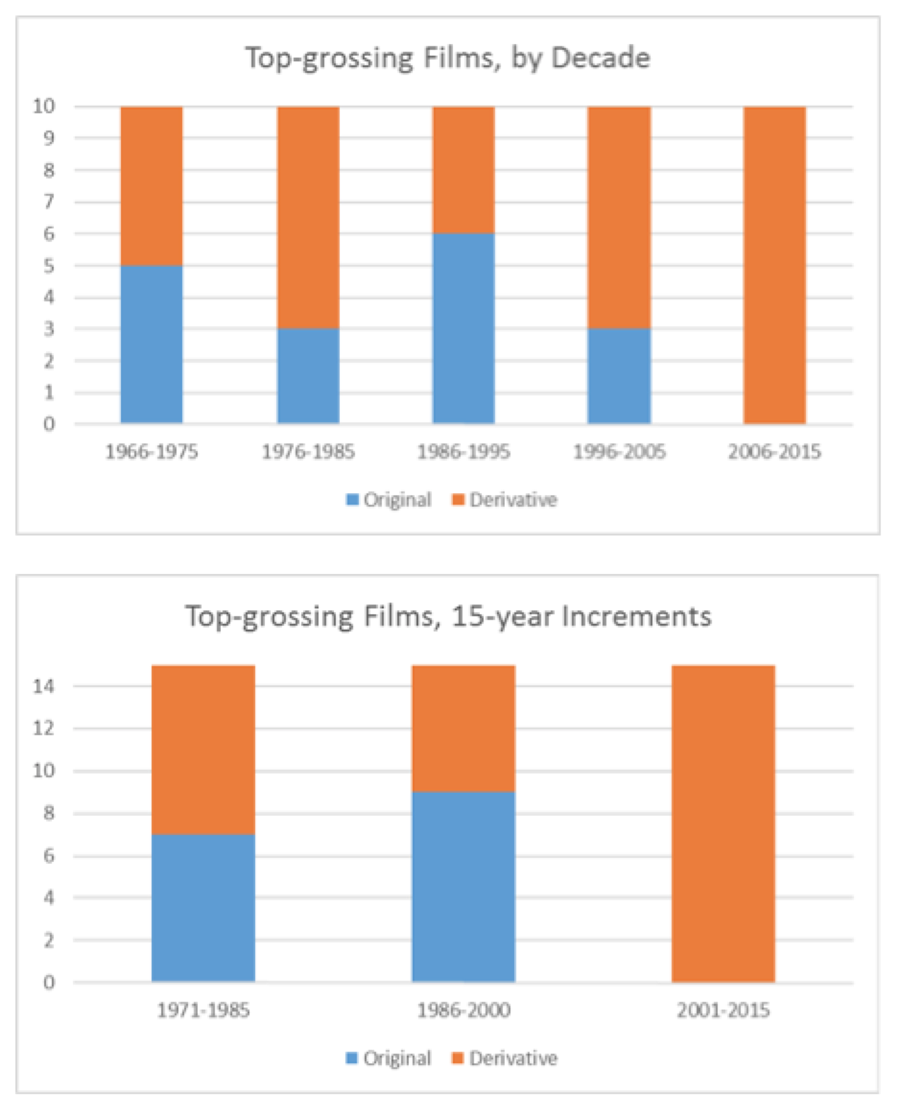

Let’s start with film, since the rise of pastiche is especially visible there. One of the most straightforward tests is to look at whether the top-grossing film of each year is an original story or relies on references to past work, then compare the relative numbers of “original” vs. “derivative” films over time. This should tell us something about broad societal preferences.

To simplify things, let’s look at sequels and remakes, which by definition fall into the “derivative” category and can be spotted without doing too much cinematic background research. Yes, you could reasonably argue those don’t count as true pastiches, but they do undoubtedly fall within an ideology of pastiche—a pastichism—where people prize references to past art over original artistic expression. Sequels in particular are telling, because Hollywood’s decision to continue investing in a pre-existing storyline, as opposed to striking out with something new and fresh, is a good barometer of our collective appetite for derivativeness.

Commercial film has always been a derivative format, so we would expect to see a certain baseline number of sequels, remakes, and dyed-in-the-wool pastiches. However, we see a virtual takeover starting in 1999. In the 17 years since then, only one of the #1 blockbusters, Avatar, has not fallen into the sequel or remake category. And of that exception, Avatar director James Cameron has described the film as a pastiche of sci-fi stories he read as a kid.

By contrast, if you look at the previous 17-year span, there were only 6 remakes or sequels. Everything else was original drama. And the trend holds true no matter how you slice the data. Look at the decadal average from 1965 to 2015, and we see more or less equal numbers of original vs. derivative top-grossers, with a slight uptick in originals in the 1980s. If you look in 15-year increments, it’s even more clear. At the turn of the millennium, boom, everything changes.

So is pastiche just a corporate marketing ploy?

I doubt it. Marketers in the commercial arts sector have certainly picked up on our newfound obsession with pastiche, but they didn’t create it. Why would they bother? Commercial art marketing isn’t about artistic expression, it’s about the path of least resistance to your wallet. There was no clear trend toward pastiche in previous decades (in fact, the ‘80s saw a trend toward original work, at least in film), and especially given the powerful analytical tools provided by online streaming, it’s never been easier for the commercial arts to follow rather than lead.

Turning to pop music, this is exactly what we see. The major labels invest a lot of money into streaming data analysis, looking for the next big hit or rising indie band. In interviews, major label execs speak to a strong listener preference for pastiche. All of the most popular stuff is derivative-sounding music that combines elements from other well-known sources, whether in the form of genre fusions like “country rap” or stylistic tributes like Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines.”

Most listeners today are not that adventurous: they like music that sounds familiar. But perhaps more shocking: most listeners are less adventurous than even the record execs used to believe. Prior to the streaming data era, Top 40 radio played twice as many unique songs per day. The commercial music industry has reduced the variety in its radio rotations as a response to online streaming data.

That’s certainly not the story of payola-style boosterism foisting ever more crappy music upon us. It’s the story of a listening public that wants to hear the same thing repackaged over and over again with slight variation. Of course, none of this is to say that people can’t appreciate unfamiliar music given the right context, but our default preferences have moved more strongly than ever toward pastiche.

Spotting pastichism in art music

An ideology of pastiche is equally present in new music, although often in more subtle forms than we see in Top 40. Nevertheless, “appropriation designed to be recognizable” is a visible trend for a wide stylistic range of composers, in contrast to Stockhausen’s “always waiting until I’ve found something that I had never imagined before” or Lachenmann’s “rigidly constructed denial.” I present for your consideration a few choice excerpts from music reviews:

[Jason Eckardt’s] piece ‘After Serra,’ a musical response to the sculpture of Richard Serra, moves toward a reconciliation of uptown and downtown. — Richard Dyer, The Boston Globe

Fausto Romitelli’s 2001 “Amok Koma”… Rock elements merge with the timbrally sweeping tactics of the French “spectral” style, to coolly entrancing ends. — Josef Woodard, Los Angeles Times

Stylistically, the Philadelphia-based [Jennifer] Higdon comes down firmly on the side of tonalists, but she also knows her way around a spiky dissonance. Reminders of many a 20th-century composer may float to the surface of the concerto from time to time… — Tim Smith, The Baltimore Sun

[Nicole Lizée’s] “This Will Not Be Televised,” is a work for turntablist and chamber orchestra… fragments of old recordings are scratched and pitch-shifted, leading the acoustic ensemble on a merry chase through a fractured but brightly colored soundscape… — John Schaefer, eMusic record review

Mohammed Fairouz’s “The Named Angels” is a smooth cocktail of Middle Eastern dance tunes and film-noirish Minimalism. Ken Ueno’s “Peradam” offers a heady brew of harmonies flickering with microtones, harmonics and vocalizations that draws heavily on the individual talents of the versatile Del Sol [Quartet] players, which in the case of the violist Charlton Lee includes eerily accomplished samples of Tuvan throat singing. — Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim, The New York Times

I could go on and on. Recognizable appropriation is everywhere in new music; the only question is which materials we’re combining.

The death of originality?

To be clear, I certainly don’t think any of this means we are less creative than previous generations of composers. Pastiche sometimes carries pejorative connotations, but those stem from another time when the ideology of “hide your sources” was still dominant. Today’s “attribution designed to be recognizable” is a source of tremendous originality.

To my ears, one of the greatest modern practitioners of this new pastichism is British composer Richard Ayres. Consider, for example, his No. 35 (Overture) for two pianos, euphonium, and timpani, which flits rapidly between a wide range of stylistic references, oversized gestures, and extended techniques:

Ayres’s music is often funny, but it is also strikingly earnest and devoid of irony. His is a complex, nuanced oeuvre: some of it is very intimate and fragile, some bombastic and silly, almost all of it unafraid to show its seams, much of it uncomfortably at odds with modernist aesthetics. And most importantly for our purposes, there is nothing else that sounds like Ayres. He’s one of the most distinctive voices in composition today.

In my own work, I’ve found pastiche-inspired thinking to be a conduit for creativity. It focuses the development of the piece, and it provides an “in” for the audience: a baseline of understanding that helps them relate to the artistic project on its own terms. Sometimes the appropriation itself serves as the main focus of the development, but it doesn’t have to; sometimes it’s just a supporting character that connects the dots.

My Concerto for Mozart Piano Videos falls at one extreme, where appropriation sits center stage. It is a pastiche of concerto form structural elements, Mozart piano music, and the experience of listening to music on YouTube. In preparing the piece, I took Creative Commons–licensed videos of amateur pianists playing Mozart, chopped them into short clips, and mapped a clip to each note of the standard piano range. I then wrote a concerto for orchestra and keyboard soloist that uses this audio-video sampler as the solo instrument. The result is a whirlwind of recontextualized associations, all pivoting around rubato piano figures.

In both cases, pastichism led me to new and fulfilling types of musical development I might not have considered otherwise. It also seems to stand out for audiences. Despite the very different approaches to appropriation above, listeners of those two pieces (and others relying on pastichism) have predominantly shared reactions that stem from pastiche thinking. For the concerto, people speak (not surprisingly) about the novelty of the setup but also about how the Mozart source material was completely transformed in their minds. For the erhu piece, people remark on how the instrument seems to fit so naturally within the context of a piano duet, despite its non-Western heritage.

Why is this happening?

Until recently, I hadn’t thought of framing my work or that of my peers in terms of pastiche, but now that I have, I see it everywhere. Which of course raises the question: why is this happening? Broad societal trends are invariably complex, so I won’t pretend to have any kind of a comprehensive answer, but here are a few preliminary theories:

Access. Information technology has given us instant access to more music of more diverse types than at any point in history. As we’ve seen above, this hasn’t translated into broader musical palettes for the majority of listeners, but it has for those of us who really care about sound, like composers. It makes sense then that we would draw upon this diverse cultural history to inform our work.

Noise. Music is everywhere; it’s virtually inescapable in everyday life. That makes the experience of hearing music less special. Nobody today would throw things and boo like they did at the premiere of The Rite of Spring. The bigger problem is that people simply don’t notice music washing over them; everything unfamiliar simply becomes so much noise. And composers aren’t immune. As a reaction to this collective numbing, we are increasingly attracted to the use of familiar elements that can cut through the indifference and serve as a sort of Trojan horse for our artistic ideas.

Biology. There are limits to what the ear can hear and the mind can process. As I’ve written previously, this puts an expiry date on experimentalism in music. We have long since passed the point where composers and instrument-builders could come up with sounds never before heard. Technologies like Max/MSP will continue to improve, performers will gain better fluency with extended techniques, but the sounds of 100 years from now will not be unrecognizable to us in the way the sounds of today would have been 100 years ago. It’s impossible. We’ve already heard all the sounds the human ear can hear. All there is left to do is combine them in new ways.

Plurality. Despite the Donald Trumps of the world, we are—on the whole—much more accepting of the perspectives of others than we were in decades past. It is not socially acceptable to be openly racist or sexist, nor to privilege the Western canon over other musical traditions. As a result, our composing becomes more self-conscious and seeks on some level to be respectful of other traditions, often by giving them attention in our creative thought.

Nostalgia. Perhaps due to a combination of the above, nostalgia is very popular right now. While traveling recently for a performance, I crashed at a friend’s place. He was excited to show me his collection of ‘80s cartoon VHS tapes, valuable because of their kitsch appeal and the obsolescence of the media format. Similarly, the resurgent popularity of vinyl is tied to a nostalgia for a time where you couldn’t access all the world’s music instantly and had to make conscious choices about what you were going to listen to.

DJ Culture. We’ve had at least a couple of decades to get comfortable with the idea that musicians who combine the recordings of other musicians in novel ways are in fact creative artists in their own right. Beyond that, social media memes and other online collage genres have made the act of creative appropriation a common cultural experience. Perhaps these developments make us more receptive to the idea that there are valid artistic paths outside of the 20th-century “hide your sources” mentality.

Half a century ago, Marcel Duchamp stated: “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution.” Today, we’ve taken that philosophy a step further by blurring the lines between spectator and artist, transforming the act of spectatorship into a fundamental part of the artistic process.

Aaron Gervais is a freelance composer based in San Francisco. He draws upon humor, quotation, pop culture, and found materials to create work that spans the gamut from somber to slapstick, and his music has been performed across North America and Europe by leading ensembles and festivals. Check out his music and more of his writing at aarongervais.com.