In the garden at the Church of the Ascension

New York, New York

April 17, 2013—2 p.m.

Filmed, condensed, and edited by Molly Sheridan

Transcribed by Julia Lu

Poster image by SnoStudios Photography

Stacy Garrop is a composer of remarkable balance and discipline. Her composition catalog neatly covers all manner of ensembles, and her subject matter has ranged from Medusa to Eleanor Roosevelt. She may not be one to aggressively sell her music at cocktail parties, but she won’t shy away from cold calling performers from her desk the next day. She teaches her students to identify their weaknesses and figure out how to manage them. It’s a lesson she applied to herself first, pinpointing personal composition hurdles and designing neatly efficient ways to combat them.

When we met during rehearsals for her choral work Love’s Philosophy in New York this past April, she moved between performance preparation with the singers in the Church of the Ascension sanctuary and on-camera conversation in the venue’s garden courtyard, fielding questions about her music and her career with an easy confidence but a notable lack of pretension. Those character traits are perhaps what attracted her to the Midwest, where she now makes her home. Though raised in California, her education brought her to the University of Michigan, University of Chicago, and finally Indiana University. She eventually settled in Chicago, where she now heads the composition department at the Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University.

Stacy Garrop is also a composer with stories to tell. The role of narrative—whether indirectly or overtly applied to the final composition—is a central factor in her typical working process. In it, she had found a way to shape and chart the sonic image she wants her music to ultimately project to the world beyond her studio.

When all is considered, Garrop appreciates that it’s a mix of many factors that have contributed to the music she makes and the success she’s achieved, but ultimately it hinges on what she is willing to do for the work herself:

I think you not only have to have the discipline to write and to get back to people and to be on top of your website, but you also have to be disciplined about chasing down opportunities. You can’t just sit back and think that maybe a publisher will do that for you, or maybe your recording will get out there and, miraculously, everyone will want to do the piece. I just don’t know if one competition or one recording or one piece can change your path all that much….In general, these careers are slow building. They’re one step at a time, and you have to be organized to make that happen.

They are steps Garrop keeps taking. The evening following our interview, the Voices of Ascension performance of Love’s Philosophy won her The Sorel Medallion in Choral Composition.

***

Molly Sheridan: You’ve spoken often about the place of narrative in your work, so I thought we might begin by discussing how important that is in terms of your working method, and how vital it is for you to communicate that to the audience. Are you demonstrating that storyline to them in the music and the program notes, or is that simply a private part of your own working process?

Stacy Garrop: As a composer, I’m both a visual and auditory person. The visual part likes to see a story in my head—like a movie, basically. It’s not that I’m a movie composer, because I’m far from it, but I feel like if I can tell myself a story, and have myself follow that story as I’m writing, then that narrative will help me guide the shape of that piece. Sometimes I think it’s important to the audience: If it’s about Medusa, I want people to understand that Medusa is going from being lovely to being hideous. But other times the narrative is just mostly for myself. So I have a piece called Frammenti which is basically five miniature movements, but each is based on an abstract idea. For me, what was important was the narrative within each movement—Is it going to get louder? Is it going to get softer? Is it going to get boisterous?—whatever those characteristics were. In that case, I don’t care if the audience gets it or not. That’s not the concern of the piece.

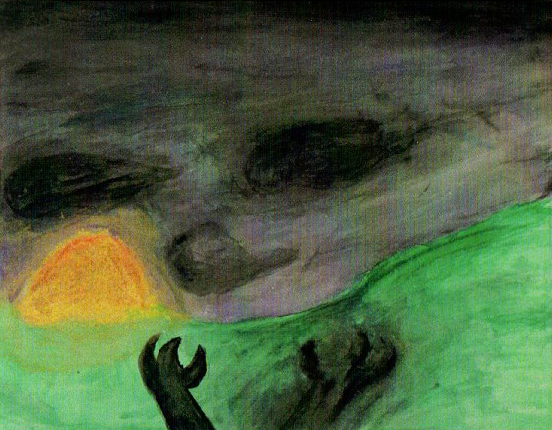

MS: I heard you speaking about the working process surrounding Becoming Medusa in a promotional video, and you mentioned sketching it out and thinking about it narratively in a way that I would imagine a novelist might. What is your working process in that case?

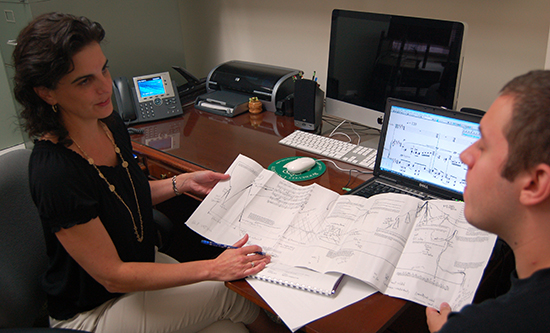

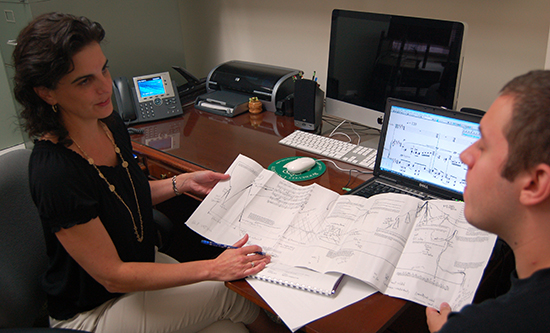

SG: I do like to use charts a lot. In years past, especially when I was working on Becoming Medusa, I had a picture where she was half beautiful and half ugly. I put that up right in front of me as I composed. But I also have a line graph that basically shows tension along the y-axis and time along the x-axis. If it starts with Medusa being ugly, because it’s a foreshadowing, then I’ll have a big spike on my chart and that might say “introduction.” Then I get to the A material, and the tension is now very low. So I can track and write out the form of the piece before I actually start putting notes down. But usually I try to put a few notes down—at least get motives, some idea of what I want to play with. Then that starts to suggest more and more of a shape to me. Usually by the end of the first couple of days, I have the shape down, and more often than not, when I go back and look at it [after the piece is done], I’ve actually attained that shape. Earlier on, I wasn’t so good at that. But now I seem to be doing much better.

Garrop explains the graphs she uses while composing.

MS: What are you actually thinking about when you’re in that very, very early process and you’re making shapes and charts?

SG: The worst part of composing for me is the beginning of a piece. I can’t get settled. If the apartment is messy, I have to clean it. I feel like I have to get my mind in order. And if there’s anything distracting me, I’ll use that as an excuse to run away from the paper. But what I have learned over the years is to just get myself to sit down long enough to brainstorm on a blank sheet of paper—not even manuscript paper, just written ideas about what I want for the piece. So for Medusa, I wanted to tell the story that she starts off the piece as a beautiful woman, who then taunts a goddess. Then the goddess turns her into the gorgon that we know. That’s a slightly different story than the Medusa that we know about from the movies. That gave me enough to say, okay, this is what I’m going to do in words. Now I can sit down at my keyboard and start just noodling around and see what kind of ideas I can come up with from there.

MS: Because your attraction to words is coming up again, why not use words? Why use music to tell these stories?

SG: Actually I’ve started to try to write short stories. I take the El to and from work every day in Chicago, and it’s about a 45- to 60-minute train ride. I absolutely love science fiction short stories, so I started trying to write them. It’s really hard to have that kind of control over words. I have that control, I feel, over music, but not at all in words. So right now it’s a really fun, but kind of scary, side venture. I did try writing poetry much younger in my life, until I discovered Edna St. Vincent Millay and then realized I had nothing on her. That was pretty much it for my poetry days.

MS: But you do feel comfortable writing music?

SG: Yes, once I get past the problem I was describing about not knowing how to get started. Another thing that I do to really help with that is I have what I call a “minute a day” challenge: Every day when I’m starting a piece, I have to write a minute of music. It doesn’t have to be good. It doesn’t have to be bad. It just has to be a minute of music. And that way I feel like at the end of seven days, I’ll have seven minutes of music that I can choose from and start to say, “Okay, that’s a good idea over here, but that’s terrible”—and we just throw that part away. But that gives me some choices. Usually I start that within whatever genre I’m working in. So for instance, right now, I’m working on a piece for the Lincoln Trio, and I’ve been looking at a lot of piano trios. I’ve been looking at Joan Tower’s Trio Cavany and Aaron Kernis’s Still Movement with Hymn, which isn’t actually a piano trio. It’s a piano quartet. But I’m writing a 25-minute piece, and both of those pieces approximate that length. So I’m looking at their ideas, and then I’m brainstorming about what it is that’s important to me that I want to put in there.

MS: You’ve mentioned that you’re a visual person, and I know that somewhere you said that your studio was the mostly brightly decorated room in your home. What do you like to surround yourself with when you’re doing this work? You mentioned pictures and charts, but is there more to that visual comfort zone for you?

SG: My husband and I finally were able to get a condo. It was really great because we’ve been in apartments for so long where you can’t put any paint on the walls. So I painted my studio purple. Then, in addition to that, I went to a lot of colonies back when I was in my early 30s, and I kept meeting all these artists. That’s where I really started getting the visual interest going. So I started collecting pictures, both from trips I was taking and from colony experiences. I also began trading CDs of my music with other artists at colonies. So I’ve had visual artists draw pictures for me or paint something, and all the artwork I’ve collected is sitting on one whole wall of my studio. I also go to a lot of art expositions and things like that. I mean, I can’t really afford the art itself, but artists tend to make these little postcards that have a picture of their artwork, so that goes up on my wall, too.

I also have done pottery for ten years, and I feel like doing pottery helped me think about process in a whole other way. It’s the same thing I got out of going to artist colonies where you sit down with a filmmaker or a writer, and you talk about their process. Then you start to see, wow, they’re using a different language, but they’re also talking about how you get from point A to point B and in a way that’s convincing. Pottery has also taught me a lot about patience. If you are at all trying to force a piece to happen, you’re going to nudge the clay, and then it’s going to be forever ruined. So I think that kind of patience actually has helped me back in the composing world: To just take a deep breath, do my thing where I write a minute of music a day at the beginning and know at the end of that week, I am going to have options. I think all those things are processes that let me know that I don’t have to go with my first impulse. I can really take my time and find the ideas that I feel very strongly about.

MS: That’s a very tactile thing to engage with, too. I suppose composition can be, depending on your working methods, but it’s not quite the same thing.

SG: I think composing is such an isolated thing. Obviously, we have our concerts with performers and all that. But the creation itself, the process for me is sitting in a room by myself, working at my piano. So to be surrounded by 20 other potters and hearing all these conversations going on as you’re trying to work, it’s the utter opposite experience of being a composer. Also, it teaches you that it’s okay to mess up. I think we all get to a level in our careers where we feel that it’s scary to mess up. If we mess up, someone’s going to notice and they’re going to write a review that isn’t positive. In pottery, I feel like I can just mess up all the time, and no one will ever know. I just stomp it back down into a lump of clay and try again. So it’s given me some freedom that I don’t have in the musical world.

MS: What is your musical background? You were a pianist originally, right?

SG: I did play piano, although I was never very good. I can admit that. I sang in choirs starting in third grade and all the way through my master’s. I absolutely loved singing in choirs. I was an alto, and I think that’s why I write such good, juicy bits for altos in choir pieces, because I always felt like we got cheated. I also played saxophone in marching band for three years in high school. So I started off doing all that, but then in my junior year of high school, there was an AP music theory class. The teacher was a jazz trumpet player, and he said one night to go home and write a piece of music. I’d never before thought that anybody wrote music. I was pretty naïve as a kid. I’ll admit that, too. I mean, I know I was naïve because I thought all the history had already been written. But in this case, the minute he said go home and write a piece of music, it was like this door opened that had always been shut. Suddenly there it is and you’re looking at a whole new room, and all these colors are there. I just didn’t want to leave it. So, after that assignment, I just started writing more and more pieces. Then a friend of the family hooked me up with a composer in the Bay Area, and I studied privately with him for the rest of high school.

MS: Voice is obviously something you’ve spent a lot of time with, but overall something that stood out to me about your catalog is that you’re a very balanced composer. You have all the bases covered. It’s a very neat though broad package.

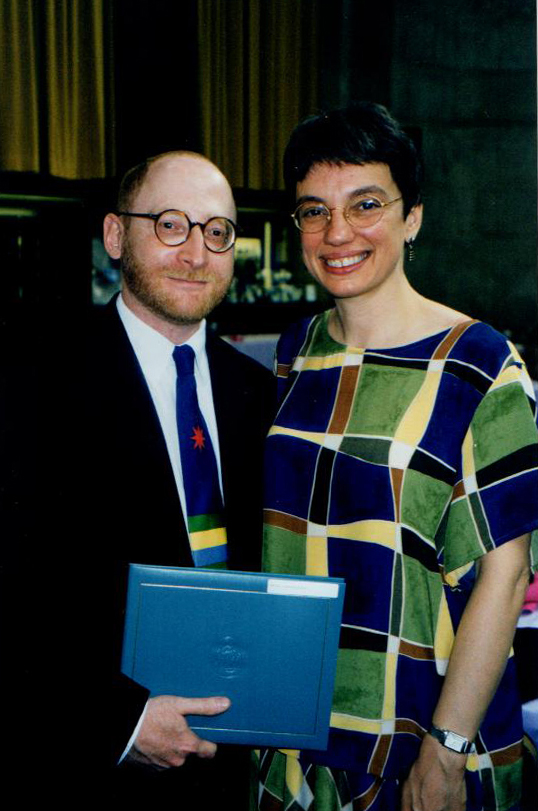

Garrop with the the Capitol Quartet after the premiere of Flight of Icarus March 2013

SG: I think that was maybe more a result of the schools that I went to. The first was University of Michigan, and they had a really good percussion program and very strong saxophone program. That’s also where I saw composers writing for orchestra and I began experimenting with string quartets. I went to the University of Chicago after that. That was a research school and I really didn’t have as many performances. I discovered that I was probably a happier person if I’m at a performance school. So, I got my master’s, and I went on to Indiana University. They had six orchestras, choirs everywhere, and, once again, they had a strong saxophone program and a strong percussion program. So that really helped open some doors that otherwise I might not have considered. All the saxophone writing I had done is because of the saxophonists that I met, especially Christopher Creviston who is teaching now at Arizona State University, Tempe. We were students together at Michigan, and he asked me to write a piece. Fifteen years later he found me and said, “Do you remember this piece?” And from there, that’s led to a commission with his current group, Capitol Quartet, for saxophone quartet.

But I do feel like I try to be balanced. I want to have orchestra, choir, and chamber, and in particular within chamber, I want to have piano trio and string quartet and saxophone music at all times. I really do want that kind of diversity. The problem I feel like is that there are certain pieces I want to be writing and I’m not necessarily getting the opportunities to yet. For instance, solo piano. I can’t believe out of everything I’ve done, I only have two solo piano works. There was one more at one point, but I didn’t think it should last the test of time so I destroyed it. But other than that, it really is quite funny that I’ve gotten this far without more solo repertoire.

MS: I was curious about another aspect of your works list because there is one piece from ’92 listed in your catalog, and you can the count on one hand material from the late ’90s, and then this huge body of work explodes from there. I’m trying to do the math on your age and where you might have been at that point in your education. Did something concretely shift for you in there, artistically or circumstantially?

SG: It’s funny you noticed that because I feel like, as a composer, I have a sliding scale of what I think works. I call it seeing the holes. When you’re writing a piece, you think it’s perfect. You’re thrilled. Maybe four to five years later, you start to see the holes in it, and realize, okay, that’s not as strong. Maybe it can be two years. But as I was going through school, I was changing and evolving so quickly, that the seeing-the-holes period was only about six months to a year. It really started lengthening after I finished my training or was getting close to finishing my training in Indiana. So what I took out were almost all the student works.

The reason why the one from 1992 is in there is because it’s my first string quartet. I didn’t want to eradicate it. I’ve gone on and I’ve written three more string quartets, and you can’t call something number two if there’s no evidence of a number one. And honestly, for a student piece, it’s not that bad. So I’m okay with it being out there. Actually, that piece helped get me onto a concert series that helped change and shape my entire career. So it’s not bad to have these student works out there, as long as you’re okay with it getting performed. There have been a few other pieces along the way, like the piano solo I mentioned. It took about a year to realize that it wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on, and I should just remove it from my catalogue. So I think for me, the test of “Am I getting better as a composer?” is, “Do I have less of that happening? Is my catalog staying steady, or am I taking things out?” So at this point, I think I’m doing pretty well.

MS: I was wondering if that was the direction you were moving or if there was a danger you could just become increasingly hypercritical of yourself.

SG: I’m really not that worried about it. There are certainly a lot of areas that I’m very comfortable in now, like the chamber world and the choir world especially. Orchestra writing is always a little trickier because you try to get the balance as well as you can between the woodwinds, the brass, and the percussion and everything, but it takes going to the rehearsals to really start to sort out what’s really going on. But I feel like now, if I know I’m writing badly, I stop myself much sooner. That was my mistake years ago. I wouldn’t do that one minute a day trick, I would just go with my first impulse and, more often than not, I knew along the way that something was wrong. But it was too late. The commission was due, etc. So, what I’ve done is start each piece with just brainstorming for a week. No pressure to just delve into it. That really helps, as well as having a big buffer zone on commissions. If a commission deadline is, let’s say, September 1, I will actually have that score due a month or two before that in my own calendar. Then I have the pressure that I need to make the work happen, but if I’m unhappy with the piece, I know that I’ve got the time to fix it.

Garrop lecturing about various Chicago artists and their websites.

MS: Every time I speak with you, I take away the impression that you are a very disciplined person, both in building your career and making your art.

SG: I feel like going for the doctorate really teaches you how to organize your head. I think that’s the biggest thing anyone can learn going through school. All the time I’m telling my students, you have to figure out how your mind works, and then figure out where your strengths are. If you know where you’re weak, like you’re a procrastinator, you’re going to have to work around that. So I feel like for me, the challenge of all the years of school was figuring out all those issues, so when I graduated, I could really hit the ground running as a professional.

In addition to being organized, as much as I can be, I took on some campaigns earlier in my career. So I wrote a choir piece. I would cold call 30 choirs, and I would send out a recording and the score. I did campaign after campaign like that, but they paid off. It only takes one person programming that piece to then lead to four more commissions. So I think you not only have to have the discipline to write and to get back to people and to be on top of your website, but you also have to be disciplined about chasing down opportunities. You can’t just sit back and think that maybe a publisher will do that for you, or maybe your recording will get out there and, miraculously, everyone will want to do the piece. I just don’t know if one competition or one recording or one piece can change your path all that much. I mean, granted if you were to win something like the Pulitzer or the Grawemeyer, perhaps. Or even the MacArthur. But I think in general, these careers are slow building. They’re one step at a time, and you have to be organized to make that happen.

MS: You don’t strike me as a particularly aggressive self-promoter. So, for you to have started cold calling ensembles in such a strategic way is unexpected. Where did the idea even come from?

SG: The funniest part is that growing up in California—not that California has anything to do with it—I was just very laid back and shy. I guess in my undergrad years, I learned to make friends with musicians. But it wasn’t until my doctorate that it finally hit me: If I was going to take control of my career, I had to do it myself. No one else was going to do it. There was one defining moment where I put this all together. I was staring out my window and realized I could keep staring out that window forever, or I could get off my rear and start making phone calls and get a recital together. And I went with option two.

The campaigns though, I think it’s because I watched too many people in academia who had wonderful music, but it wasn’t getting out there anywhere. And I would ask, “Well, what are you doing about it?” And they would say, “Oh, you know, just getting it published,” or “Just getting it recorded.” It didn’t seem like that was the best strategy for me. I would need to start to push it out there further. I didn’t go to any East Coast schools, and I wondered perhaps if I had, if maybe some more connections would have been presented. But nonetheless, I felt like, okay, I can do this. I just looked at Chorus America, ACDA, the North American Saxophone Alliance. You look at some of these big websites and see who their members are. Chamber Music America is a particularly good one for that. Actually, I did a campaign in the last year or two using Chamber Music America. I got [a list of] all their member string quartets and piano trios, and I sent them all information. This time through email, since now it’s become more acceptable.

MS: You have written a lot of text-based or text-inspired pieces, which makes sense to me considering your narrative interests. It surprised me when you said Edna St. Vincent Millay’s work squashed your own poetry ambitions, because you’ve actually set a lot of her work!

SG: It started because one of the very first artist colonies I went to was the Millay Colony in Austerlitz, New York. While I was there, I was working on a piece for saxophone and piano called Tantrum, but I came across a book of her poetry, of course, and thought, since I’m here, I should give it a whirl. I began reading her sonnets, and they were just so eloquent—14 lines long and having a rhyming verse, but still relevant today. I just thought, okay, I would love to do some massive project, where I set—I think I was aiming for originally about 30 of her sonnets. As the years went on, I think I wrote one sonnet set per year from 2000 to 2006. I got around number 17 or 18, and I finally had to call it quits because a very wise conductor, Christopher Bell of the Grant Park Chorus in Chicago, said to me, “You should really set something other than Millay. You should have more in your portfolio.” And he was right. I was just so thankful that he was blatantly honest with me. Composers need to hear that honesty every now and then. And that’s when he said, “You really have to get past the Millay and move on.”

It’s been really tempting to try to go back and finish the project. I had actually paired up a bunch of sonnets into particular sets. So there’s a set about love, and there’s a set about war, and so on. Maybe someday I’ll go back and visit that. In the meantime, I’ve done other big projects involving text. One is The Book of American Poetry. That’s about an hour of music, and it’s four volumes of poetry. Each volume contains five poems by five different poets. I set the first ten for baritone and Pierrot ensemble, and the second ten are for mezzo and Pierrot. But then I’m also making piano arrangements of all of them.

MS: You’ve done that in a few places, right, offering options on work to give it a broader life?

SG: Yeah, I wrote it for Pierrot ensemble because it was for the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble. They had a competition, and I won and they said, “Okay, what do you want to do?” I said, “I want to do a Book of American Poetry.” Once they understood the scope of my project, they were on board. But then I discovered that it’s really hard to get Pierrot ensembles together elsewhere with baritones. So to give the piece more life, my husband is doing the piano arrangements for volumes one and two, and I did the arrangements for volumes three and four.

I’ve done it the other way, too. I wrote a piece called In Eleanor’s Words, about Eleanor Roosevelt; that’s a big song cycle. It started off as a piece for piano and voice, but then David Dzubay at Indiana University and I were talking, and he said, “I’d love to have you come out for a residency. What pieces would you like to have done?” And I said, “How do you feel about an orchestration of In Eleanor’s Words?” So that’s when I created the larger version. That’s also when I discovered that it’s much easier to go from large down to small than it is from small out to large. At least for me it is.

MS: In all these examples of your interest in stories and setting text, it strikes me that these are not your personal stories, but very often items of historic importance or mythology or poetry. What about that speaks to you so strongly?

SG: I wish I knew. I mean, some of these things happened because of commissions. In Eleanor’s Words was a commission by Tom and Nadine Hamilton. They’re residents of Washington, D.C., and they commissioned a piece in honor of Tom’s mother who had been in public service all her life and who liked Eleanor Roosevelt. Since I teach at Roosevelt University, it made sense to put it all together, and what do you know? Out comes a piece. I think that it’s easy for a composer to just see what the flow of the commissions are and to just go with that, whereas if you really have your own agenda, you have to start to force that every now and then. So in the case of the Millay sonnets, I felt so strongly about that project. When I did that cold call many years ago, where I sent out my music to 30 choirs, Volti in San Francisco was the choir that answered. They not only performed the piece that I sent them, but they commissioned three or four others over the next decade and many of those were the Millay sonnets. I said to them, “I want to do Millay. I want to do this big cycle.” And they said, “Great! Let us help you out.” So it’s great to have commissions, but it’s also great to have a clear idea of what you want to achieve and make sure that you work that into your commissioning schedule, if you can.

World premiere of Garrop’s Songs of Joy and Refuge by PEBCC’s high school mixed voice choir Ecco, conducted by Clifton Massey on March 23, 2013. Photo by Don Fogg

MS: Where did you get this business sense? It seems like you have a really smart way of approaching your career, and I’m curious where you learned this.

SG: I don’t really know. I think part of what happened is I saw how other people handled their careers. For instance, there was a guy at Michigan when I was there. He was very talented musically, but he also had this incredible gift to be able to walk up to anybody and sell his music to them, to basically say, “Hey, I’ve got a performance tonight. You should go hear it.” He would walk up to performers he’d never met and hand out his music. I tried to emulate it, and I just felt sick to my stomach. I couldn’t do it. It was not in me. About 12 years ago, as I was getting out of school, I just made the decision that if it took me a little longer to have a career, then that’s the way it was going to be. I’m not the person that’s going to be really in your face all the time. So that’s where I started getting very good at campaigns, and getting good at having a web presence, and doing a lot of business through email. If someone emails me, I answer within 24 hours. So all those parts put together I think eventually started to fill out the bigger picture. Sometimes I do wonder, maybe my career could have moved a little faster if I’d been a little bit more aggressive, but I would not have been comfortable doing that.

MS: Yeah, but on the other hand, you clearly have found what does work for you.

SG: Right, but I think it took all that experimentation back in school and trying to emulate the behavior of others to realize, “Oh, I can’t do that,” or “Okay, that worked.” I think it was observing that really helped me figure out what I wanted to do.

MS: Very early on you mentioned specifically that you’re not a film composer. I was curious about that. For as diverse as your portfolio is, and as much as you love exploring storylines, I don’t believe there are any film scores or video games in it. In a way, that seems like it would be a natural affinity, but you stayed away from that.

SG: It’s not so much staying away as it is that I really haven’t stumbled across the opportunity yet. I have to admit I know a little more about video game music than I should. My husband plays these games, and I realize the music is getting quite, quite advanced. I would love to go into writing movie music, but I’m in Chicago. I’m not on the right coast. Although I do think it would be hard for someone like me. The things that interest me the most in music are form and tension and relaxation. So if there’s not a strong formal structure, then I’m not happy with the piece. What can be hard about writing for movies is that you’re constantly having that formal structure ripped out from under your feet. If you have to extend it by five seconds or they don’t like a theme that you wrote and you have to rethink it overnight—that can be hard if you’re used to having final, set structures that you really feel good about. So, I’d love to explore it someday, but you know, sometime in the future. Not any time soon.

MS: You mentioned not being on “the right coast.” How important is Chicago to you? What made you decide to build a career and life for yourself in that place?

SG: People used to say to me when I was in school, “You should pick your last school carefully, because that might be where you end up.” And I thought, “Ha-ha, that’s really funny!”, but I actually did end up in the Midwest. All my schools just circled the Midwest area.

I feel like Chicago has been really good for me. In the last 15 years, maybe even the last 7 years in particular, there’s just been an explosion of ensembles. So we have new music ensembles. We have choirs. We even have a new opera company that has formed. It’s a great time to be in Chicago. So for someone like me, it’s been a perfect city to not have to go to New York—no offense to New York. It’s a great place to visit, but I’m more of a Midwesterner I would say at this point.

MS: That’s interesting because you came from the West Coast, right?

SG: I’m from California, and I have to admit, every time I go home and visit it’s like, “Why did I give this up? It’s so beautiful out here.” The weather is nice almost the whole year through. But I think at that time, there weren’t enough composition teachers in the West Coast area. Almost all the schools I looked at were in the Midwest or on the East Coast. I have also really enjoyed building a composition program at Roosevelt University. After going to two very large performance schools where there’s a faculty of five or six people, it was a little bit surprising to go into a program of just two people. But that also allowed me to shape it a lot faster than I probably could have if I had been at a major performance school. So my colleague Kyong Mee Choi and I have really tried to focus on giving opportunities that you might not get in a regular college setting. We bring in people like Timothy McAllister, the saxophonist from Prism Quartet, or Timothy Monroe, the flutist from eighth blackbird, and they do workshops with our composers. They sight read the works; they give feedback. We have a competition, and they choose a couple winners and perform the pieces on concerts at Roosevelt. We do the same with Gaudete Brass Quintet—all the students have to write little fanfares. We’ve been having the Vector Recording Project with the orchestra, so students don’t just get a piece read, they actually get it professionally recorded.

Particularly with continually rising costs for a university education, I’m asked by prospective students about the value of a college degree as a composer. In looking back over my own training, I couldn’t have learned all the skills I needed to outside of a university music school—my high school music training had been weak, and I had many, many skills to acquire before I could call myself a composer. I feel that attending a university as an undergraduate is very important to one’s development as a composer, as you get a complete, well-rounded experience over the course of a four-year program. Depending on what you wish to do next, you may have enough skills to exit straight into the real world and carry out a career, or it could be that taking the time to get a master’s first will help you obtain even more skills that you’ll find useful. People who wish to teach at a university need to earn a doctorate in order to have the credentials schools are looking for when hiring, but if you’re not planning on doing so, perhaps you don’t need to go any further if you’ve developed your skills far enough. So it is important to start thinking about what it is you truly want to do when you graduate. Is it to teach? Write music for movies? Start a new music ensemble and write music for it? Investigate what skills you need to attain your goal, and work on developing those skills while still in school so you’ll be ready to hit the ground running when you get out. Play to your own personal strengths. Hopefully you’ll discover a path to a career that will make you feel excited, enriched, and rewarded.

I think a lot of schools are coming around to the fact that they need entrepreneurship programs, and Roosevelt at the moment doesn’t have one yet, but I believe they’re moving in that direction. Nonetheless, I know a lot of us have integrated ideas into our courses. For instance, in my composition seminar last year, all my students had to get into groups of three or four and create new businesses. They had to have a mission statement, a five-year plan, a ten-year plan, and then had to have a website up or something to show that this is what they do. It was really exciting for me to see just how creative they got. It really taught me that they want to be able to put this together before they leave. A part of my job is to really give them professional opportunities that hopefully bridge the gap as they’re leaving the school. They are starting these conversations with professionals. They know how to build their own website, and how to write their own CV or how to go knock on doors and hand out scores. I’m hoping that gives them an edge—that they have not just the compositional skills, but when they walk out the door, they have the business side somewhat already going. Hopefully that will increase their chances of being successful.

MS: How do you make enough room for your own music and your own career in the midst of that work?

SG: It can be a bit of a challenge. I feel like I have to choose my commissions very carefully in terms of when I write what. This past fall at the very beginning of the semester, I wrote one choir piece, and then I wrote a piece for two trumpets and piano and then two art songs. That took me up to probably mid-January. Then I started a piano trio, and that was my downfall, because I got all those short pieces done while teaching—it doesn’t take as much concentration to do a six-minute piece here, or a five-minute piece there. But to do a 25-minute piano trio while teaching, especially during audition season, I learned I’m not capable of that. So that’s one thing: Strategize your year. The other thing is I don’t go into Roosevelt all five days. I try to go in just four, and some lucky weeks, I may just get in three, depending on how many meetings we have. But I find I’d rather work longer days downtown so I have a full day to compose when I’m off. I’m not the type of person who can just turn around after a long day of teaching and somehow have energy left to start composing. I can answer emails. I can send out scores. I can do that other business work, but I can’t actually be creative.

MS: Do you need a specific time of day or routine, or do you just need an actual day where you don’t have to separate the administration from the creativity?

SG: It is better if I just have a whole day, or a week, or a month, or a year. I think that’s why the art colonies were so fantastic, because it removes you from paying bills or anything else. You just sit and you compose all day. I have an 88-key synthesizer, but it’s right next to my computer. So if my computer is turned on and dinging at me as email comes in, then of course you stop composing. I’ve learned I have to just turn everything off. Pretend nothing else exists and just get myself into the space. I mentioned earlier, I think starting pieces is always the trickiest for me and I do a whole thing where I have to straighten up the condo and all that. But once I’m into the process, it’s really quite comfortable to move in and out of it. So I can get up and answer an email, or go get the mail, or whatever, and then come back and be right back into the piece wherever I left off. And that usually lasts up until I finish the piece.

MS: You mentioned the period when you were going to a lot of those colonies. Is that something you had the freedom to do just because of where you were in school or is that something you expect you’ll do throughout your life?

SG: I think I started going to colonies because one of my teachers, Claude Baker from Indiana University, said I should take a look at them. I applied to a few, and I actually got into the ones I applied to. So that’s when I just strung them all up in a row and colony hopped for the year after I finished my coursework but before I’d actually finished the dissertation. One of these was the Banff Center for the Arts in Canada. Another one was the Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach, where I got to meet Aaron Jay Kernis and we worked together. Then there was the MacDowell Colony and the Millay Colony, and other ones in between.

That’s where I just finally put it all together. When you’re in school and you’re reading books, you’re writing papers, you’re certainly obtaining the knowledge, but you don’t necessarily know how to apply it yet. I felt like that was the first time I learned how to take all that information I’d been collecting and apply it in whatever facet I wanted to. So for me, it was a really great eye opener. I think it gets harder though as you get more responsibility to be able to carve out the kind of time that you really need to go to a colony. I seem to have stopped going for the moment, and that’s fine. Maybe someday I’ll feel the need to go again, but I also have a home studio situation now, which is pretty quiet and which works very well. That hadn’t always been the case in past years. That was another reason to go to these colonies—to have the space and time where I really wouldn’t be disturbed.

MS: You’ll have to go back to the Millay Colony and finish the settings; it’s the perfect application.

SG: Well, that’s just it. When I started the whole process, I had no idea I was going to compose all these sonnets. So I really want to go back and actually write the final sonnets up there. That would be really cool. I think they have a policy where they don’t want people to return, but they do have these small residencies in January, where you can just go with maybe a specific project. It’s not necessarily the actual colony stay. So what I need to do is get my act together and put in an application for that particular type. The thing I regret when I went to the colony is that you’re supposed to get a tour of Millay’s house. It’s left pretty much intact from the day she died. But the day that we were supposed to go, the caretaker’s wife went into the hospital. So part of me feels like I want to go back and get that tour, man. I want to just confront whatever ghosts might be there and just say, “I set your poetry. Don’t be mad at me.”

MS: For as interested in narrative as you are, as a listener, I’ve never felt overwhelmed or emotionally manipulated by that aspect of your work. Instead it’s like being a third-party observer. Is the audience in your mind when you’re composing and is there ultimately a reaction you’re looking for, that you’re listening for in the lobby after the performances? Or is that not a part of your process?

SG: I think there have been moments where I’ve been genuinely concerned how an audience might react. Most of the time I’m not. I think that my language tends to be more accessible than not, so I guess I’m kind of lucky that way, or I’ve made the choice to be that way. But there’s a moment in my String Quartet No. 2, the third movement called Inner Demons, where you’ve heard four themes presented in a scherzo-trio form, and then they all begin to mix together and it’s chaos for about a minute straight. I was panicking before that first performance and wondering if people were just going to tune out or get disgusted. Will anybody do the ultimate “stand up and storm out” thing? When it premiered, I did see a lot of heads turn and people look at each other at that moment. But it passed. They all got through it. The rest of the quartet finished, and it turned out to be, I think, the strongest movement of that piece. So I feel like it was a really good risk to take. Sometimes you just have to not worry about how the audience is going to react.

What is interesting, though, is a lot of times people won’t tell the composer what they really think, but they don’t know who the composer’s husband is. So, there’s been many times where my husband has been circulating in the lobby after and he’ll just hear bits of conversation, and that gets hysterical. So that’s how I really get my feedback. It’s nice when people come up who are supportive, but I would love to occasionally get someone who says, “This part was great, but this other spot didn’t do as much for me.” It’s great to get past that first level and say where’s the feedback? I really need to shape this piece into something stronger. Because I do feel like the first performance is really just a debugging session. It’s not a perfect piece by any means. I’m lucky if I get it 95, 96 percent right. And it’s the second performance where you get it to about 98, 99 percent. And finally, by the third performance, that’s where I think it should be completely settled.

MS: Do you have any reservations about doing serious editing after the first performance?

SG: I will absolutely do it if it needs it. In the case of Becoming Medusa, it was [originally] a minute and fifteen seconds longer than it now is. There’s a minute in there, and another 15 seconds elsewhere, where I just felt that this is not doing anything for the piece. It’s wasting time, and it’s taking away from the rest of the moments. So I had to butcher it, but I think it made for a stronger piece. It is hard to do; it is hard to face up. I think it can also be harder the longer you wait. There’s a piece right now in my repertoire, and it needs a revision, but it was written so long ago now that it’s hard to rip apart. I’m no longer there as a composer. I don’t know what was important to me necessarily that I want to preserve, and what things I should put in that are important to me now in the re-write.

MS: Considering that evolution, when you look back, do you feel like the career that you’ve had so far is the one that you expected to have, either when you went into undergrad, or when you left your Ph.D. program? Have things turned out the way you expected?

SG: I guess the funny thing about me is, I knew I wanted to be a composer, but I didn’t really know what that would be. I knew I wanted to be successful, but I didn’t know what that would be. The one thing I was sure of is that by the time I was 30, I would be married and have kids. I turned 30, and I wasn’t married, and I didn’t have kids. So the one thing I was so sure about did not happen. In a way that freed me up—anything’s on the table. I can go out and do anything I want. I’m not sure if I’ve really attained all the success that I thought I’d have at this point, but I’m very happy with what I have achieved so far. That doesn’t mean that I don’t have more goals, and I have plenty of projects that I want to be doing. So I’m not quite where I want to be in the future, but for as little as I knew when I was getting out of school, I think I’m doing quite well.