A conversation in Kernis’s New York City home

February 11, 2014—10:00 a.m.

Video presentation and photos by Molly Sheridan

Transcribed by Julia Lu

When he was just 23, he was thrust into a kind of stardom that many dream of but few ever achieve. He reached one of the top levels of fame in a career which, at the time, rarely paid attention to someone so young—in fact, in a career that rarely paid attention to someone alive. He was aspiring to be a composer of orchestra music and it was the early 1980s. The name John Adams, whom he had recently studied with, had just barely started to register in the national consciousness. This was before the Meet The Composer Orchestra Residency Program was launched. Sure, Philip Glass and Steve Reich had already become familiar names, but it was certainly not due to orchestra concerts. But a major American orchestra played a piece by this young composer on a festival that was attended by critics from all over the country. The conductor of the orchestra attempted to show him who was the boss during an open rehearsal. He talked back. The audience ate it up and he became something of a cause célèbre. He was suddenly the next big thing, the person to watch.

He continued writing music and went on to receive a bunch of accolades for it. While still in his 20s, he was signed by one of the top music publishers. By his 30s, he was signed to a five-year exclusive contract with a major record label and he won the Pulitzer Prize. Not long after turning 40, he received the University of Louisville’s Grawemeyer Award, which is the single largest American award for composers. He was at the top of his game, so to speak. But at the same time that he was pursuing his craft and being successful at it, he decided to devote a significant part of his life to being a mentor to younger composers and help them attain the same kind of achievements that he has had. He founded the Minnesota Orchestra Composers Institute, one of the premiere programs for nurturing emerging talent, and oversaw its activities for over a decade. To this day he’s on the faculty of the Yale School of Music whose successful composer alumni nowadays seem ubiquitous.

He’s had a pretty complete life, so much so that later this month the University of Illinois Press is publishing a biography of him, a rarity for a living composer. But he’s only in his early 50s. What do you do with your life after all that? Where can you go from there? What’s life like after someone writes your biography? It’s a tough act to follow. But that is the conversation we were eager to have with Aaron Jay Kernis.

Kernis claims that his biggest epiphany after reading through the proofs of the book (it’s not an unauthorized bio) was realizing that there were connections between pieces he wrote that he originally felt had little relationship with one another. He thought he had abandoned post-minimalism in his youth. The angry angular pieces from the early ‘90s (like a symphony he wrote in response to the First Gulf War) also seemed worlds away by the time he was composing the vast soundscapes of the past decade. And how to explain how any of that related to the numerous laments he has composed for lost family members, friends, even John Lennon whose murder inspired a gorgeous rhapsodic piece for cello and piano, one of the earliest pieces of his that’s still in his active catalogue?

I did not have the reaction of wanting to flee but rather to explore that question of “which of these Aaron Kernises am I?” … For a long time I thought it was always a completely different direction, but now I see that there are circles; it circles back with new perspectives, new materials. … When I finished the book the first time, I thought about my newest work. Are these works related? Or are they something totally different? I don’t have the perspective yet. I don’t have enough distance from them to know quite where they fall on the continuum of cycling relationships. … I’m a different person than I was when I was 29.

But mostly he doesn’t worry about neatly sorting out these connections and just tries to balance teaching, raising a family, and writing music. When we visited with him in his cluttered apartment near the northern tip of Manhattan, where children’s toys freely mix with books and scores, he had just completed a viola concerto.

I have work time during the day and time with my kids at night. It’s very special time, unlike any other. And I don’t travel to performances as much, unless they’re premieres. I love to travel, but now it’s time to travel with my kids. Luckily I’m in a situation where I can teach one day a week and have the rest of the time to compose. It’s a full day. Sometimes it spills over to another day, or some students come down here and we have some extra time. But I try very much to fit it into one day. My composing time is really pretty sacred.

I’m glad he took some time out of his schedule to talk with us.

Frank J. Oteri: There’s a weird contradiction to your music. On the one hand, it’s very much of this time; many pieces are directly informed by mainstream popular culture. But, on the other hand, it seems to go against the grain of whatever our zeitgeist is supposed to be. Of course, to have your own voice, you have to fight against the zeitgeist.

Aaron Jay Kernis: But what is the zeitgeist? It’s always shifting, and it’s so large. That’s the thing about our time. The formative musical experiences I had were from college radio. And my worldview became one of just everything—‘20s jazz, minimalism, hard core, uptown stuff, lots of Irish folk music, all over the place. The idea of this multiplicity of possibilities was a great way to start. But the problem with that is that it sometimes makes choosing difficult for me, so I kind of move back and forth between things that continue to interest me.

FJO: But some things interest you more than others.

AJK: Oh, definitely.

FJO: So why are certain things constant recurring themes for you? You just mentioned ‘20s jazz, but ‘50s rock and roll and even disco have inspired you.

AJK: Right.

FJO: Everything figures in, but you eventually have to strip things away. It’s like you’re sculpting, chiseling at the musical universe to get at an essence, rather than adding to it.

AJK: Things appear and then they vanish for five or ten years. I’ve seen that very much with any interest I have. Actually, it’s kind of an interesting time now, because my daughter loves Top 40. So every morning, or pretty much any time she’s in the car, we’re listening to Top 40 together. I’m pushing her toward the independent rock stations, because I’m curious to see, in a language she’s most interested in, what cool stuff I’m going to hear. But mostly, any rock and roll, disco, or salsa influence appeared in a short period of time, and then pretty much has vanished and was replaced by the influence of jazz, which is a core kind of thing from my childhood. But I’m really curious about your provocation about not being of this time.

FJO: Well, one thing about your music that stands out is how so much of it revels in the long line and long forms. This is definitely at loggerheads with our era of limited attention spans and instantaneous gratification. I couldn’t imagine you on Twitter, for example.

AJK: And I’m not. You’re right. I’m not planning to be, but I have been kind of curious lately. I’m not really interested in poetry, but I am interested in looking for things on the internet, maybe on Twitter, to set as texts. I haven’t gotten there yet. I’m just kind of starting to see that for myself.

FJO: I’m surprised to hear you say that you’re not interested in poetry.

AJK: Not right now.

FJO: Not now, but all your life, you have been.

AJK: Yeah, all my life. But I’m very interested in prose right now and things that may not have started as poetry, but that can be extracted and be poetic.

FJO: That seems very different from Dominick Argento’s reason for setting prose to music, which he says he does in order to not be straitjacketed by the rhythms of the text.

AJK: Well, that’s another reason I’m interested in prose, exactly. When I’ve used poetry recently, I’ve started to sculpt it more. Rather than being completely respectful of exactly what the poet has to say, I’ve started shifting lines around. I use text where I can do that and feel comfortable not using all the lines or the exact structure that was laid out.

FJO: That’s very interesting, because one of the things I’ve always noticed about your vocal music is how respectful you are of the texts that you set; you don’t even repeat lines. You let the shape of the poem determine the shape of the setting of it.

AJK: That was true maybe until the Third Symphony [Symphony of Meditations], where I had this enormous text. For shorter texts, I did pretty much respect the structure and the number of lines. But the [Third Symphony’s] texts were so large, and there were some lines I didn’t like, and it was ancient poetry. My friend Peter Cole, who was translating, was completely willing to let me do whatever I wanted with the text, and that was very freeing. So I just made my own version of the text rather than feeling that I had to respect its totality at every second.

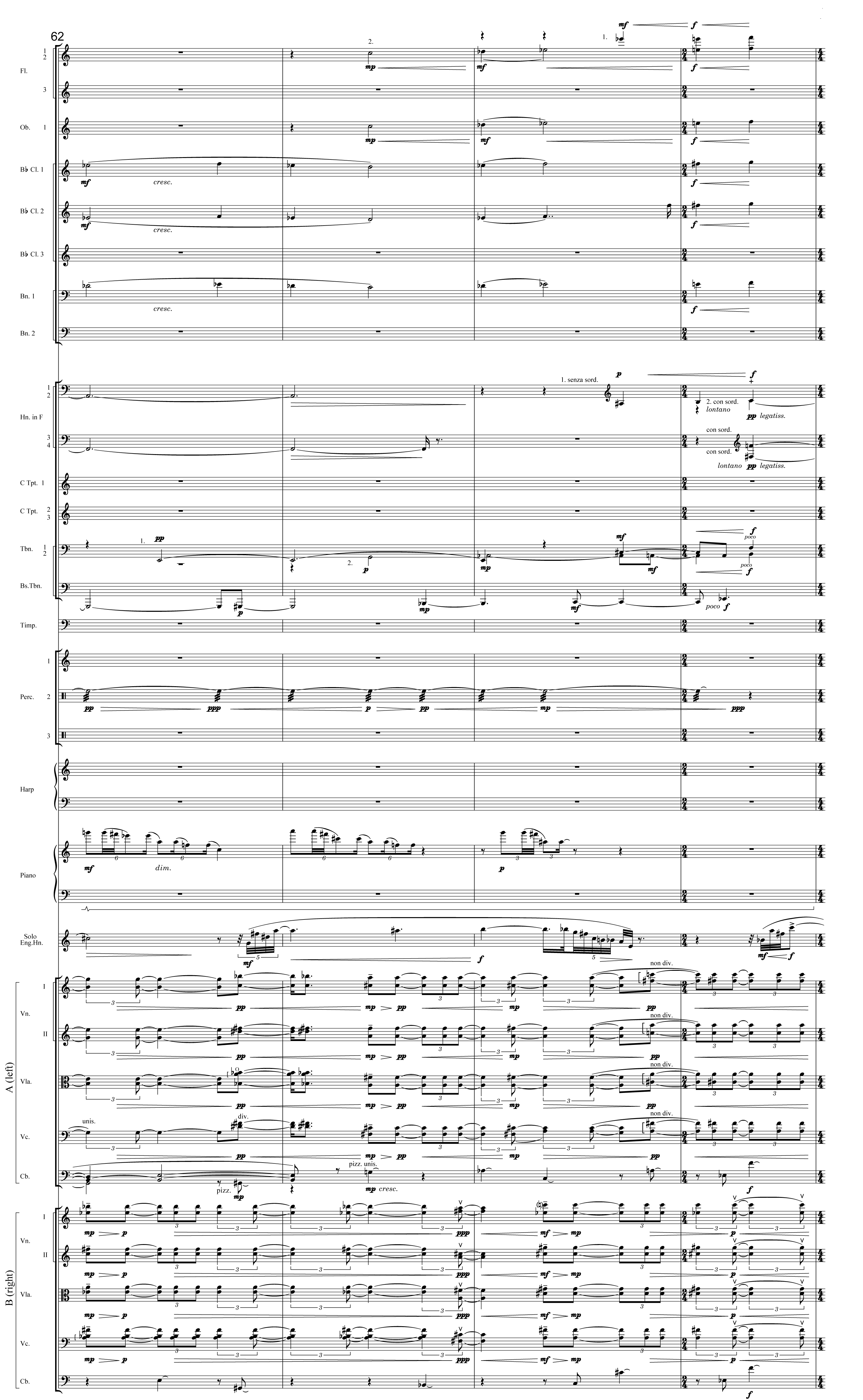

A passage from the score of Symphony of Meditations (Symphony No. 3) by Aaron Jay Kernis.

Copyright © 2009 by AJK Music (BMI)

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved.

All rights administered throughout the World by

Associated Music Publishers, Inc., (BMI) New York, NY

Used by Permission.

FJO: So you’re actually contradicting the earlier you. You’re becoming another you.

AJK: Yeah.

FJO: This makes you and history kind of a tricky thing. Of course, I bring this up because there’s a book that’s just been written about you.

AJK: Right.

FJO: Biographers always look for a through line, to try to connect the dots and to get at the essence of a person. But perhaps now that there’s a book out about you, you want to rebel against that and be somebody completely different.

AJK: I read the [galleys of the] book through without being so concerned with making corrections. I wanted to just see what the through line of the book was finally. This was about a week ago. And, you know, I did not have the reaction of wanting to flee but rather to explore that question of “which of these Aaron Kernises am I?” [The book’s author] Leta Miller very consciously wanted to draw the body of work together, rather than having it broken up into different areas. This was also my concern. We all remember having reviews that frustrated or repelled us. It was always incredibly frustrating if a critic would say, “This sounds like nothing else in his work.” Of course, I knew that. In fact, there were three or four other pieces that clearly the critic didn’t know that were part of a group. Sometimes they were three years before, sometimes just the month before. There always have been groups of works of different types. I kind of do one for a while, and leap over that and do something else, and then find my way back in a circuitous way. But there’s been a transformation, too, that usually happens.

FJO: In terms of how your work is part of history, it’s interesting to ponder earlier versions of music you have revised—because you’ve revised work.

AJK: Not that much.

FJO: Perhaps I should say reuse work.

AJK: Reuse. Yes. That’s true.

FJO: But I was thinking of one of your earliest pieces, the Partita for solo guitar, which goes back to 1981. You were 21 years old at the time. What did the 21-year-old Aaron Kernis sound like? Since you revised the piece in 1995, it’s hard to know. How much of that piece is the you of 21, and how much of it is the you at the age of 35?

AJK: Let me see if I can remember. It’s a three-movement partita. That was more of a revision. It was awkward. Some of the sections were too long. Some of the guitar writing wasn’t sustaining as much as I liked and it was kind of working against the instrument. In ’95, I wrote 100 Greatest Dance Hits, and at that time I was able to work with David Tanenbaum and tried to work through the issues in the piece. But the voice in that piece—one scale per movement with a lot of nested processes like numerical forms going on—that was a lot of who I was at 20 and 21. So I think that really does reflect me until about 1983, until I was 23. Then I’d had enough of that. That’s often how it is. I get to a point and then I want to go off in another direction. For a long time I thought it was always a completely different direction, but now I see that there are circles; it circles back with new perspectives, new materials. For example, one of the circles back was after a comment that Russell Platt made about a recent piece, Pieces of Winter Sky, that I wrote for eighth blackbird that in certain ways feels like a new direction for me. I’m not sure if it’s going to be a direction, but it’s certainly a new place to go. But Russell said, “Oh, that seems more like the old you.” The “old you” that he meant was the Invisible Mosaic II world, which was much more strongly dissonant, not really process-like in any way but more moment form. Pieces of Winter Sky is definitely a series of moments. But even in Mosaic, there was a process going on. It has a moment form and process form. So I see the relationships, but it felt very different. At 52, I’m a different person than I was when I was 29.

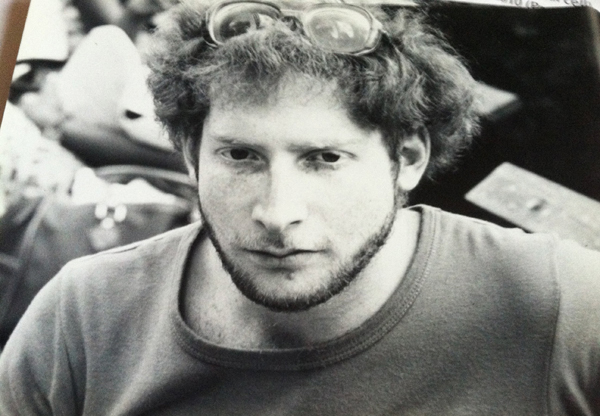

Aaron Jay Kernis in the 1980s. Photo courtesy Aaron Jay Kernis.

FJO: Has reading the book made you see those connections or is this something that you have always thought about?

AJK: Leta and I talked a lot about the connections through the whole process of [her working on] the book. As I said, that was really a major focus for her. What I’m curious to see as I reflect on this more is what the connections are that I don’t perceive. Are there patterns? Which patterns am I less familiar with and are they more revelatory? Are there any or have I known all this? When I finished the book the first time, I thought about my newest work. Are these works related? Or are they something totally different? I don’t have the perspective yet. I don’t have enough distance from them to know quite where they fall on the continuum of cycling relationships.

FJO: Well, something you definitely have distance from at this point is dream of the morning sky. You mentioned being 23 and suddenly the process wasn’t as interesting to you and you were doing other things. There are certainly older pieces of yours that are still in your catalog and that people perform. But dream of the morning sky put you in a public sphere in a way that nothing else had up until that point. Getting a piece played by the New York Philharmonic at the age of 23 was huge for you. I think it ultimately not only shaped your subsequent compositional career, but also your role as a musical citizen and mentor to other composers.

AJK: I agree.

FJO: In hindsight having had such an experience so early on definitely seems to have been the initial impetus for you eventually founding the Minnesota Orchestra Composer Institute many years later. It also seems like something that planted the seed for your ongoing role as a composition teacher. So what happened at that time that ultimately led you to a lifetime of wanting to provide that kind of compositional nurturing to other people?

AJK: There were a couple of aspects. One was that Jacob Druckman was a very supportive teacher to his students and he was very beloved by his students. He was very engaged with the music of his time and how students fit into what interested him, and what he saw was going on in music as a whole. Definitely that experience with the New York Philharmonic came about because of him, and I saw firsthand how such an experience could change one’s life. So now, whether it’s a recommendation for a commission or for a residency, I understand how important—public or private—these steps can be for young composers. For some it will make a big life difference and also an aesthetic difference; for others it will just be a step along the way. In Minnesota, when I was given an opportunity to help craft that kind of experience for young composers, it was on a much bigger scale over many years. But it infuses my teaching as well, and my view of young composers.

A young Aaron Jay Kernis around the time of his breakthrough at the Horizons Festival. Photo courtesy Aaron Jay Kernis.

FJO: In terms of your teaching, I think there’s something that’s particularly practical about the training that people get at Yale, both from you and from the other people on the faculty there. A testimony to that is how many extremely successful composers have CVs that state that they went to Yale. Obviously, something’s happening at Yale that’s creating a recipe for composers to function so effectively in this field in terms of their practical skills.

AJK: There’s no doubt that they get some of that from what we relate of our experiences to them, real world suggestions about where to look, where to go. There are varying of degrees of entrepreneurship among the faculty but I don’t think by any means that it comes from the faculty all the time, or specifically from them. It’s an environment where these graduate students, if they’re so enthused, can get involved with the drama school or other productions around campus, and already find outlets for their entrepreneurial efforts. We certainly see composers who come in and they’re already raring to go to make concert series, to put together ensembles, to get involved in the theater world at Yale.

FJO: To bring it back to your experience as a 23-year-old having the New York Philharmonic perform dream of the morning sky: the other thing, besides serving as a model for your subsequent role as a mentor to younger composers, is that it placed you as a composer within a zeitgeist, for better or worse. The festival was called Since 1968, a New Romanticism? Suddenly there was this new label. Labels always simplify things and it definitely put your music in a context which it doesn’t completely fit in comfortably.

AJK: It never did. It was a strand in my work; it comes and goes. When I was writing a bunch of pieces using sonata form, should I have been called part of a new classicism? I don’t know.

FJO: Except when you were using those forms they were big and expansive, more like the way that the 19th-century Romantic composers explored those forms than the way, say, Haydn would have.

AJK: No. I definitely think it’s more toward the Romantic, looking both at the teeming inner world and nature and art and writing; the influences are very vast.

FJO: And certainly the long line, the idea of a long melody that grows and keeps developing—

AJK: I start with that for virtually every piece. Even if today I’m sitting down to write a short piece that is the antithesis of that. I’m always thinking of myself as wanting to create the long line through singing, through breathing; that’s the starting place.

FJO: Where did that come from?

AJK: I think it came from very formative experiences as a choral singer and the first lessons I ever had as a child. My mother started me with voice lessons, just completely out of the blue. I have no idea what inspired her to do that. I think she always wanted to be in the theater. She had a dream of herself somehow in show business. And so she started me at six or something with voice lessons. I learned to use my voice a bit, then choral music, then hearing Mahler, all kinds of ringing big bells, playing the violin, and long lines there. So it’s pretty central.

Kernis’s love for Mahler pervades all of the music on a disc of his orchestral music featuring the Grant Park Orchestra conducted by Carlos Kalmar released on Cedille Records.

FJO: To take this back to teaching, this probably didn’t come from any of the people you studied composition with. I don’t really think of Druckman or Wuorinen as long line composers.

AJK: I don’t think anyone ever talked to me about that, no. I don’t have a memory of that being anything coming from any of them.

FJO: So what did come from them?

AJK: Different things from everyone, of course. My first teacher, Theodore Antoniou, was very important. He started me with kind of Hindemithian counterpoint and voice leading exercises, also some 12-tone row manipulation exercises, then a lot of looking at European avant-garde scores with extended techniques, both his work and the work of other Greek composers. And George Crumb, of course, was a great discovery of mine at 15. [Antoniou] always emphasized that if you’re writing for an instrument, the music you write should only be able to be played on that instrument. So he was always stressing the unique qualities of every instrument. I haven’t necessarily followed that all the time, but it was certainly an opening idea for a 15-year-old to really look at what the sonic and technical possibilities are that made each situation unique.

FJO: It’s interesting to hear about that from you since, by not following his advice and transforming your English horn concerto Colored Field into a cello concerto, you wound up receiving the Grawemeyer Award.

AJK: Well, of course, the cello version can’t be played on any other instrument. Though you’re right, and it’s both for practical reasons and feeling comfortable with, à la Bach, making various versions of pieces work on other instruments, sharing the love in a way.

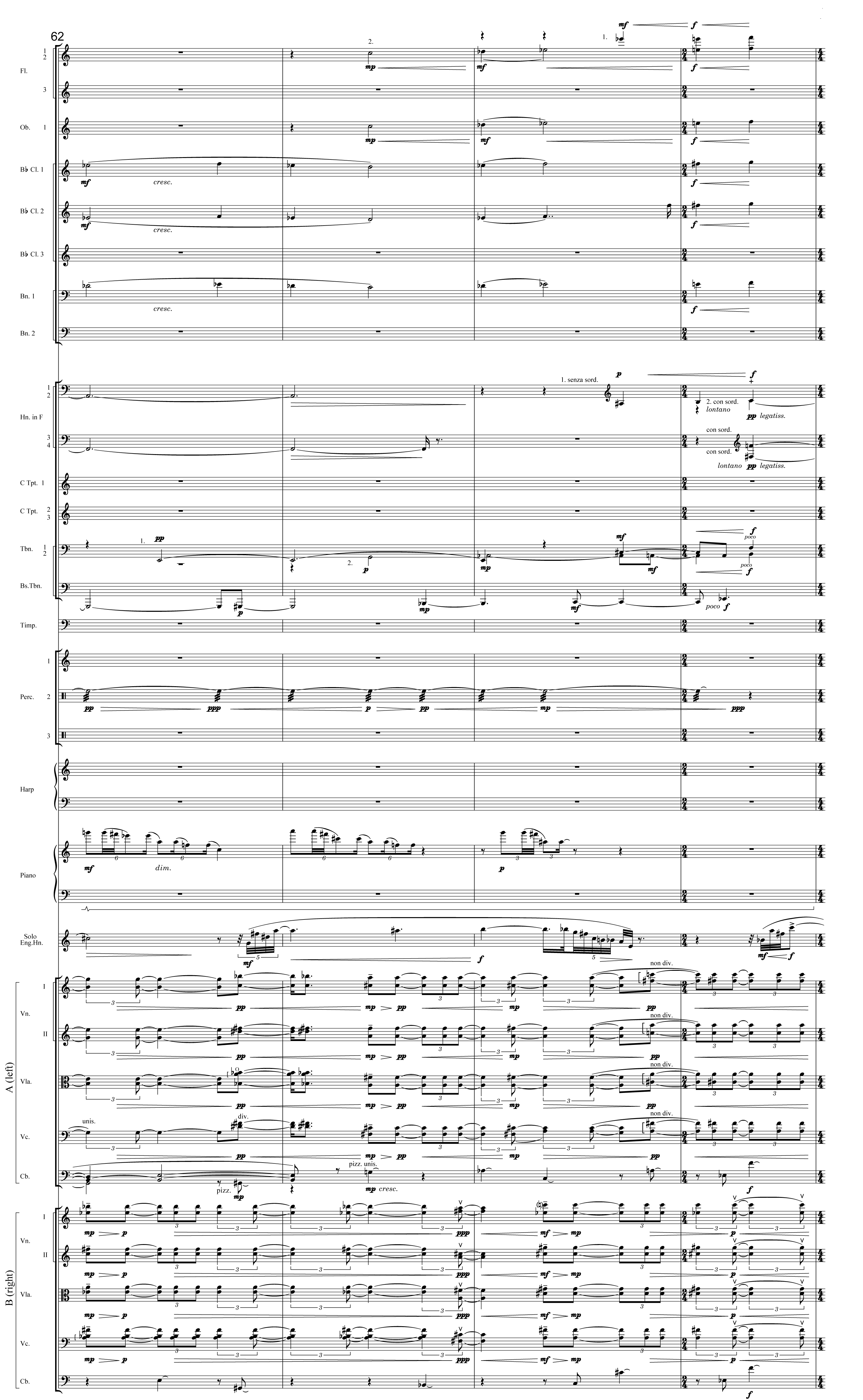

Measures 62 through 65 from the original version of Colored Field, for English horn and orchestra by Aaron Jay Kernis.

Copyright © 1994 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc., (BMI), New York, NY

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

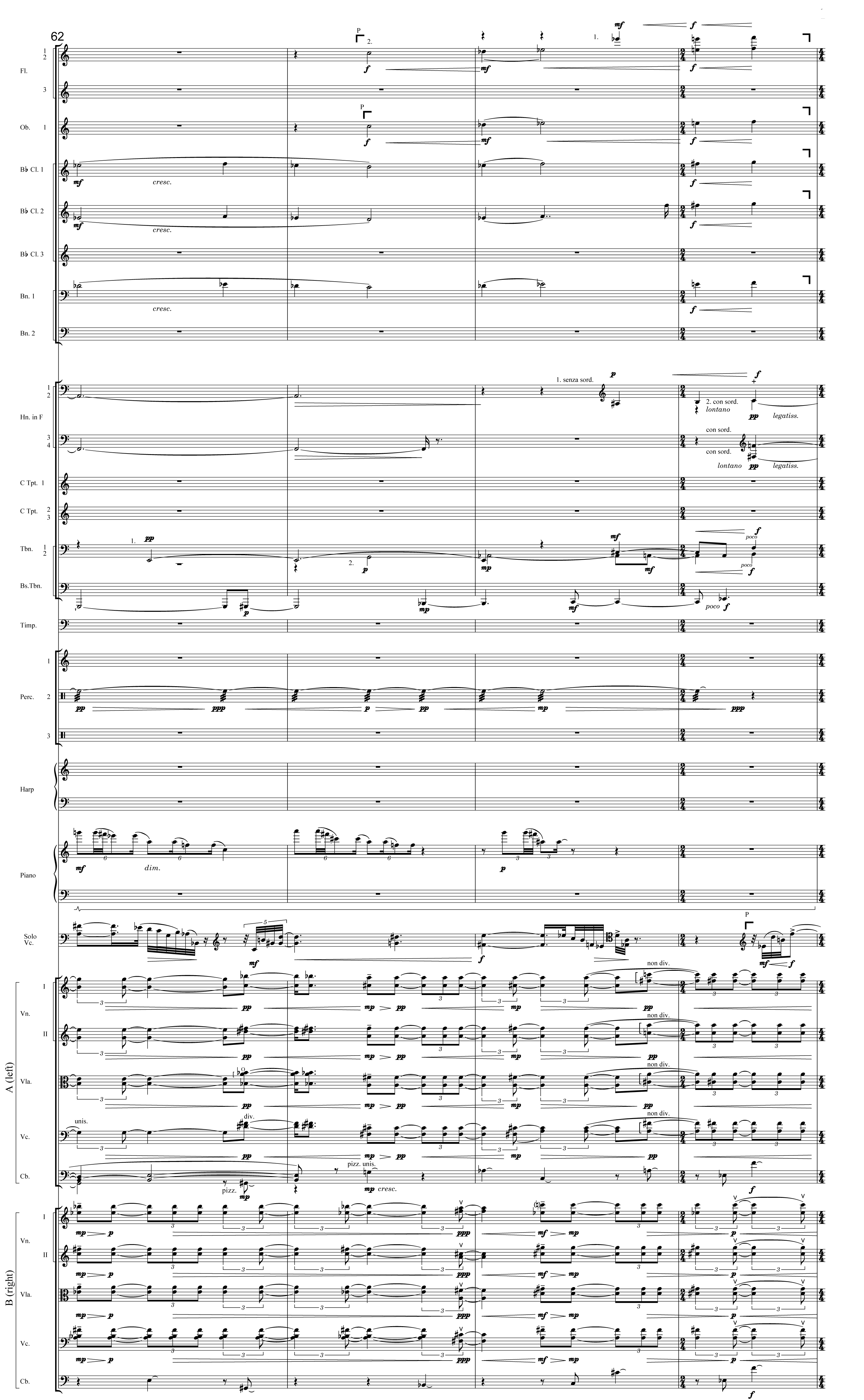

The exact same passage in the version of Aaron Jay Kernis’s Colored Field for cello and orchestra.

Copyright © 1994 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc., (BMI), New York, NY

This arrangement Copyright © 2000 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc., (BMI), New York, NY

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

But that doesn’t work with many pieces. I mean, it’s not something I’ve done for more than maybe five or six pieces; it’s not an everyday thing. When I wrote Trio in Red, the clarinet part is a clarinet part. It uses the entire range and focus, just as Antoniou would have stressed, to make it special for that instrument.

So, that was Theodore. Then through Joe Franklin, I was exposed to Relâche and the Philadelphia new music scene—a lot of early post-minimalism and highly theatrical music. After that, [I studied with] John Adams for a very short time. Certainly it was really fundamental to hear Shaker Loops in a big loft space in San Francisco and to hear his first successes like Harmonium and Harmonielehre. It was just around the time that his life was really changing. But San Francisco didn’t quite match with my metabolism; I was antsy that it was so relaxed.

So I came back to New York and studied for a year with Wuorinen and just slammed into a confrontational way of teaching. It was scary. I was terrified for a number of weeks. I was like, before a lesson, “What is this man going to say?” I knew he was a master and it was a very important year. Very much to his credit, I think he saw that I wasn’t looking to study strict 12-tone technique and so we worked through other issues: structure and language to a certain extent. Very pithy, highly focused, and very important confrontations occurred.

Then Elias Tanenbaum—I already had all this stuff to process. Elias was a great teacher to be with. He was very supportive, but also—in his kind of needling way—he made me own up to what I was choosing to do and also recognize that the possibilities were large. Following that, rather than having specific techniques that they were imparting, the teachers from that point on were more generous in the sense of following what I was doing and making comments. After that point, I didn’t feel I had teachers that were trying to fundamentally change me.

FJO: So now that you’re teaching young composers, how do you balance the need to expose students to the wide range of techniques that you’re fluent in while making sure they don’t turn into clones of you?

AJK: As I teach for more years, the goal for me has been to learn more and more patience. At first, I came in with some expectations about what I was looking for. Over time, I just dropped those more and more. It’s about each student: the work they’re producing and what could be strengthened. It’s about what kind of exercises or tool-strengthening devices could be put in their direction that they can grow from, and trying—whether it’s over a half year or a year—to figure out more and more about who they are and what their work is doing and to help it be even more of what it already is.

FJO: In terms of who you are, your composing with long lines pre-dated any of your teachers, and it has stuck with you. Being very interested in process in your early years, on the other hand, is something that has slipped away, and you have grown more and more toward writing music intuitively. But intuition is something you really can’t teach. You can’t even teach it to yourself.

AJK: No, and it’s always so awkward to use that word because even if you’re using an absolutely rigid and unyielding series of processes that essentially make all the decisions for you, even then you’re using your intuition to structure those processes—unless you’re giving over choices to an external structure like the first computer that LeJaren Hiller used. Even so, intuition is always a part. What sounds good? What sounds good to you? What are choices where you think, “Oh this doesn’t quite work; I’ll change that to make it more internally satisfying”? So it’s always very difficult to talk about becoming more intuitive. But right now it’s true. My process feels quite different. I’m more interested in going where I don’t know what the next step is and how I get to that next step, rather than thinking, “Oh, I want to go here or go here. How do I go there?” It’s a different enough change and it’s frustrating to do that for too long; it gets very tiring actually. I can’t decide whether I want to go back to a more pre-compositional ordering of some elements or to play this out for a little bit longer. You have to be so alert at every moment to leave doors open and it’s very difficult.

FJO: When you say leave doors open, what does that mean structurally? Could you give me a specific example?

AJK: This is key to pieces like Winter Sky and Perpetual Chaconne and my new viola concerto, the last movement particularly, and even Color Wheel—that’s sort of where that began but I still had some big goals along the way. I’m very visual when I write. I’m seeing a path. I’m seeing a series of steps, or of textures, or coupled harmonies that are core harmonies, that I’m heading towards. In those more recent pieces I just mentioned, there is more a sense of a series of moments. There’s still a developmental long line in those moments, but a number of them were written as kind of blocks. It’s more an assemblage than writing in a through-composed way. So I’ll write things more out of order and not exactly know what’s the end, what’s the middle. It will develop out of—as I said—a kind of more intuitive process rather than an external idea of what was going to happen when it began.

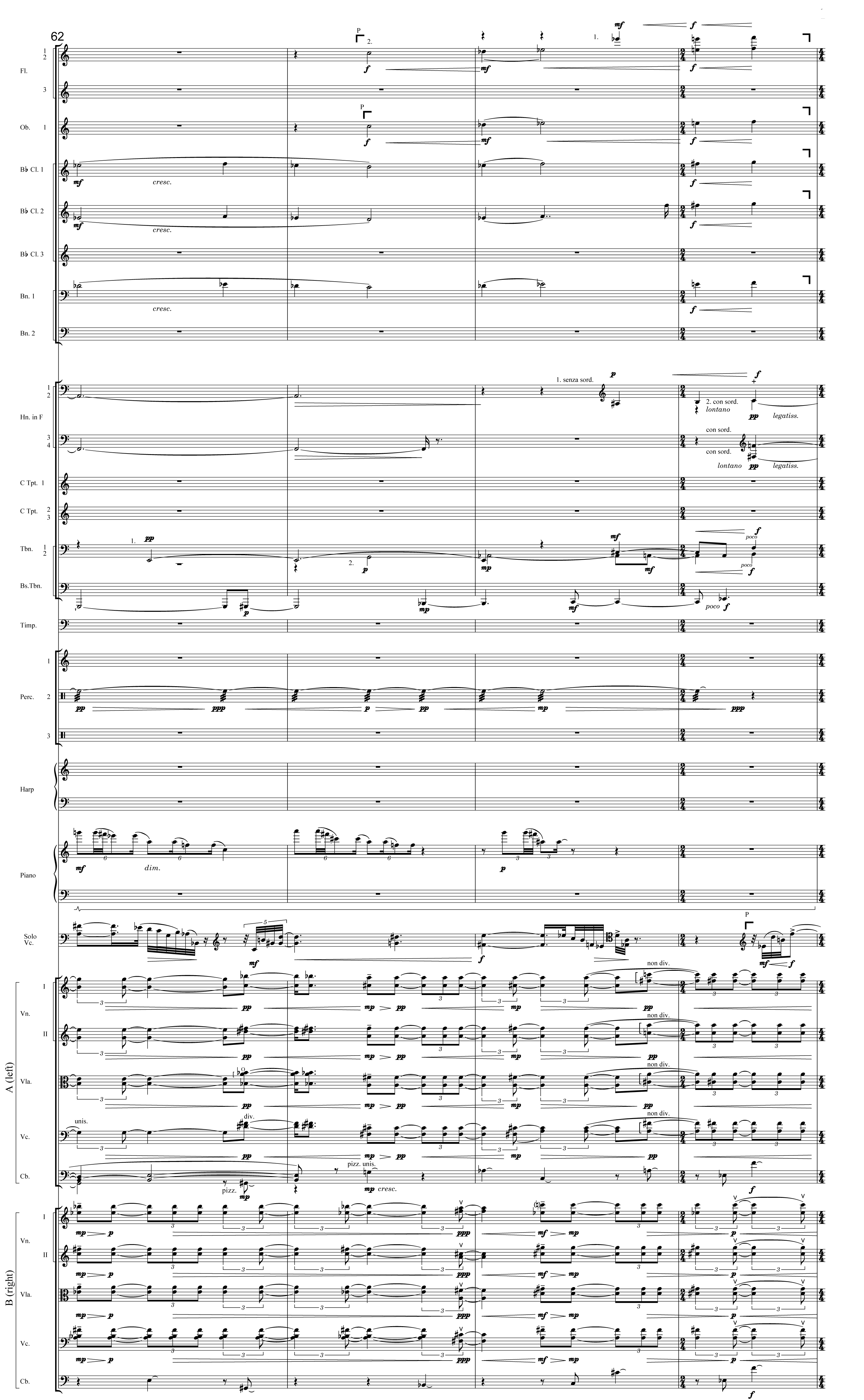

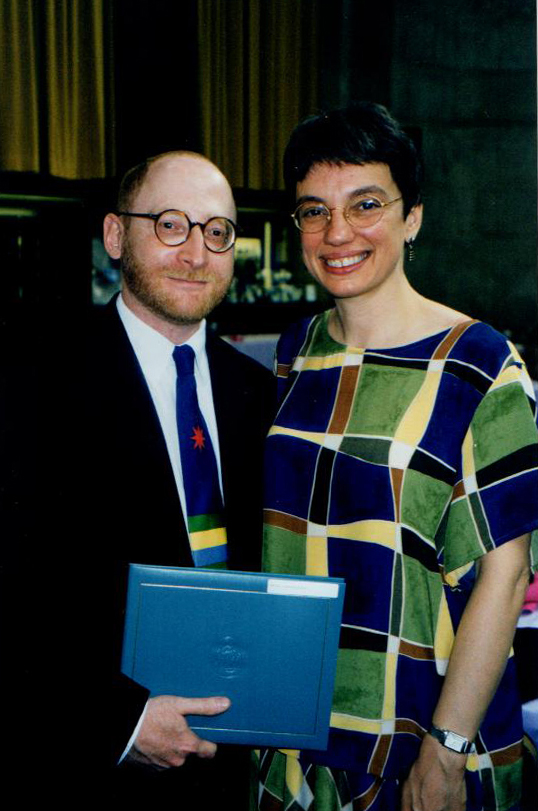

Aaron Jay Kernis and his wife, pianist Evelyne Luest at the 1998 Pulitzer Prize Ceremony.

FJO: Everything we’ve been talking about has been really abstract. But one of the main things that’s served as a catalyst for pieces of yours throughout the decades has been responding to an external source, whether it’s history, current events, or something personal such as the death of your parents or the birth of your twins who’ve now been around for more than a decade. The Gulf War inspired your second symphony. One of the most heart-wrenching stories is the story you tell of your visit to Birkenau and how that triggered Colored Field. These extra-musical elements are often what draw non-composers into this music; it has emotional gravitas in a way that, say, a Symphony No. 12 does not.

AJK: Right. That’s something that hasn’t stopped, but the influences more recently are more internal and very personal. But all of the things you mention, all of the external reactions trigger emotions. And emotions then trigger sequences of ideas or ways of conceptualizing a musical form. That’s definitely what happened. I can still feel a relationship between the way I thought about big forms in Colored Field or the pieces that I consider the war pieces, and this emotional triggering of ideas and moods. Pieces of Winter Sky is crucial for me right now because it’s like those roughly 18 pieces were like 18 melancholy studies. I didn’t want to call the piece that. In fact, it almost reminds me of that black and white film that was done with Cage’s 101—you have what seems like an unchanging series of grays that are changing very subtly—or in the late work of Rothko. That was the experience of that piece, not looking at the sky when it was blue, but for days only a slightly changing gray sky. What would it be like to write different sections that reflected variations on that, how that affected me visually? The ironic thing is that it is an incredibly colorful piece, with all this metal percussion, and all this distinctive writing for each of the instruments, going back to what Antoniou said. Yet the experience of creating it had to do with finding differences in the similarity of a fairly unchanging picture.

FJO: But the medium you express these emotional responses in is this abstract form of music. You’re not writing short stories or poetry. You’re not painting the landscape. When people hear this music, they don’t necessarily get what’s in your head, especially what you were saying about a gray sky. They’re hearing all this color with the percussion. So how important is it for you that people get this? And how much do you feel people can get?

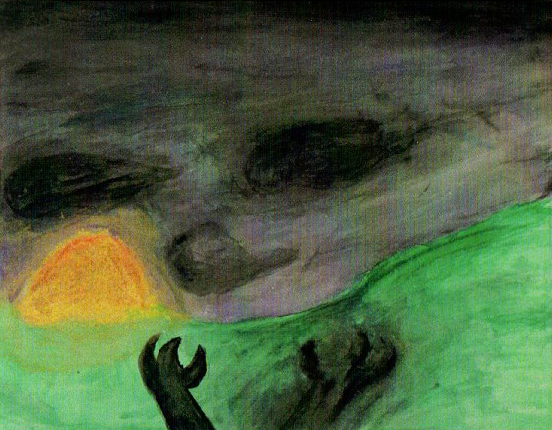

AJK: In the fall I had a performance in Princeton of Colored Field. Before and after the performance they invited a number of schools to bring their classes and expose the kids to the piece and to the background of the piece and to respond to it. I just got in the mail this incredible artwork and story writing that kids did through the experience of hearing Colored Field. It’s just amazing.

Colored Field by Shubha Vasisht (who last year was in the 7th Grade at The Hun School).

The Face in the Sky by Bailey Eng (who last year was in the 6th Grade at Montgomery Lower Middle School).

Bird’s Prey by Upekha Samarasekera (who last year was in 7th Grade at Montgomery Upper Middle School).

[Ed note: These three original art works were all created in response to hearing the Princeton Symphony Orchestra’s November 3, 2013 performance of Aaron Jay Kernis’s Colored Field by students attending nine different New Jersey middle schools through Listen Up!, an initiative of the PSO BRAVO! education program sponsored by the Princeton Symphony Orchestra. They were among a total of 36 art works that were part of the exhibition “Listening to the Colored Field” which has been shown at the Arts Council of Princeton and The Jewish Center of Princeton. All are reproduced with permission.]

FJO: Did they just hear the piece or did they also get a program note about it or some kind of pre-concert talk by you?

AJK: They didn’t get a talk from me. They might have gotten the program note, from the CD. But some of what I described as my experience is deliberately left incomplete. The thing that fascinates me most is to see the variety of responses to it. The responses could be completely 180 degrees away from what my original experience was. That doesn’t matter at all to me. I hope that people will have their own experiences and will feel something special or deeply; that’s the power of music for me. Hopefully it will allow people to recognize things inside them and maybe they can give voice to in words or maybe they have no words for it.

FJO: Paradoxically the fact that music does not have fixed meaning gives it even more meaning.

AJK: Exactly. Very well said.

|

FJO: But because you’ve referenced synaesthesia in some pieces, you obviously in your own perception feel there is transference from one sense mode to another.

AJK: Definitely. The way I compose, too. Not all the time, but a lot of times, I’m just walking around and I’m not so much imagining notes. It’s hard to explain. It’s like I’m seeing textures. I think I was exposed early enough to Penderecki, Xenakis, Ravel, that those sonic worlds created a kind of visual relationship and a kind of emotional, textual relationship. I walk around and imagine things, but they’re not necessarily fixed notes, not necessarily tuned. It’s more like how I see shapes; it’s abstract. For a long time, I would come home and try to find a way to form those into something I could feel and grapple with. Now I’ve left that step out. I’m not drawing big structural plans out.

FJO: A lot of what you have written has been memorial music in some way. The earliest unrevised piece of yours I know is the Meditation in Memory of John Lennon, which is a gorgeous lament for Lennon. I can hear a through line from that all the way to your Ballad for eight cellos, and there are many other pieces of yours along the way that have this quality, too. Remembering the dead has brought out some of your most beautiful music, your most moving and most transformative music, at least to me. I find that an interesting through line in terms of what music can mean. I didn’t know your parents, but I have a sense of them somehow because of the music you wrote in their memory. It’s not a clear sense because music is abstract, but nevertheless there’s something in there that reached me and that can reach anybody who hears it and that makes it a more universal thing.

A passage from Aaron Jay Kernis’s handwritten score for Meditation in Memory of John Lennon for cello and piano.

Copyright © 1981 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc., (BMI), New York, NY

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

AJK: The experience of writing those pieces was always very multi-faceted. In Lennon’s case, it was being around Central Park, being in very close proximity when it happened, and looking for both an element of the music of his that I loved and that affected me and finding some small way to transmit that in that piece. But any of those memorializing pieces have an element that is not necessarily one that people would hear, an element of what the importance of that person to me was in some musical way. I could tell you specifically what those are, but it’s richer than just that. There have been a lot of those pieces. My cousin Michael, who was just a few years older than me, died very young while the Trumpet Concerto was being written. And the Viola Concerto is also a kind of memorial; it’s not so much for anyone that’s passed away, but it’s about how we change over our lives, how things disappear and reappear, get together and get frayed.

FJO: Now in terms of the things that have shaped you, so far we have only talked about texts intermittently, but you’ve written tons of choral music and song cycles both for solo singer with piano and solo singer with ensemble. So text has been extremely important to you. And, when you set a text, that text already comes with its own narrative and set of emotions.

AJK: That’s a frame to hold the music.

FJO: At the onset of our conversation you were saying that you’ve started taking text and reworking it to suit your own needs rather than crafting music that will serve those text’s needs. I’d like to flesh that out a little bit more—what it means in terms of the kinds of narrative you’re hoping to tell using someone else’s words.

AJK: I’ve done this three or four times now. There’s a practical element where the texts are simply too long to set completely. Or I don’t like parts of the text. I recently did a setting of Psalm 104. That’s a huge psalm and I had nine minutes, so I chose the bits that I liked best and tried to knit them together so it didn’t seem like there was a huge hole.

One thing that made vocal music always a little easier is because the emotions are there [already in the words], and are something to respond to. And, as I said, it’s a kind of frame, a time frame to keep the whole work together that the text helps set. As my approach becomes a little bit less structured, it makes me feel freer to play both with musical form and more abstractly to not have a fixed container of the text as well. Another thing, too, is that I’ve missed having really successful collaborations with other writers and other artists. It’s something I really would like to do more in the future. In a way, this creates a kind of collaboration with the text. Even though it’s not with a person, rather it’s just taking a completely fixed form and making it more fluid.

FJO: Your mentioning collaboration with other writers immediately makes me think of opera.

AJK: Yeah, opera is something that has just eluded my grasp. The projects I had did not work out. They were very difficult, and at very difficult times also. For example, I had an opera for Santa Fe Opera. And it was not working with the writer, and in the middle of the process my mother died. Then a number of months later my father died. The kind of intensive pressure that was necessary to make that piece work in that situation was just too hard, so it just went away.

I’m not sure how this will happen yet, but I’m seeing more theater; I’m looking for playwrights. I want to keep open and not just sit here in my studio. In the future I hope that some collaborations will develop. I had a very nice collaboration with a choreographer last year, and I had at least one or two experiences with installations and that was great. I would love to do more of that.

FJO: In terms of doing things in order to put yourself in an uncomfortable zone—not having a structure, not knowing where it’s going to go, to go somewhere else. What would be maximum discomfort?

AJK: Maximum discomfort is different from finding your way without a form. The uncomfortable question is a different one, because the process of composing is always very difficult and no one is a worse critic than I am toward myself. Yet it can be extremely pleasurable when it’s going well, and when it’s purring along. I think I’m looking toward collaboration more with a sense of possibility, rather than a sense of creating more difficulty for myself, setting up invigorating challenges rather than wrenching challenges.

Kernis, his wife Evelyne and their twins in 2004. Photo courtesy Aaron Jay Kernis.

FJO: Of course, the biggest challenge is balancing it all—the music you are writing, your teaching commitments, plus having a family, two young children and a wife who’s also a concert pianist. How do you squeeze it all in?

AJK: Well, it’s difficult. Some things have had to go. The thing that’s most clearly gone is concert going. I have work time during the day and time with my kids at night. It’s very special time, unlike any other. And I don’t travel to performances as much, unless they’re premieres. I love to travel, but now it’s time to travel with my kids. Luckily I’m in a situation where I can teach one day a week and have the rest of the time to compose. It’s a full day. Sometimes it spills over to another day, or some students come down here and we have some extra time. But I try very much to fit it into one day. My composing time is really pretty sacred.

FJO: Well I’m glad you made time to do this with us.

AJK: Me too.

This photo of the corner of the piano in Aaron Jay Kernis’s composing studio taken by Molly Sheridan during our visit probably shows the combination of worlds Kernis must navigate on a daily basis even better than our conversation did.