Search Results for:

Soundtracks: June 2001

For various periods of time since high school, I have found myself trying to “be” Asian, as silly as that may sound. I suppose that having grown up “above average” (to use Garrison Keillor’s words) and white in the ‘burbs, there is nothing unusual about that; many of my closest friends have been (and continue to be) of Asian heritage. During those periods when I have tried hardest to be Asian I have generally experienced the greatest growth, personally, artistically, and otherwise. Identifying with the “Other” – cultural or sexual – can be a very powerful psychological stimulus.

For various periods of time since high school, I have found myself trying to “be” Asian, as silly as that may sound. I suppose that having grown up “above average” (to use Garrison Keillor’s words) and white in the ‘burbs, there is nothing unusual about that; many of my closest friends have been (and continue to be) of Asian heritage. During those periods when I have tried hardest to be Asian I have generally experienced the greatest growth, personally, artistically, and otherwise. Identifying with the “Other” – cultural or sexual – can be a very powerful psychological stimulus.

Of all the pieces in this month’s Soundtracks that incorporate to a greater or lesser degree references to a musical “Other,” none is so wholly representative of a single tradition as Alice Shields’ Komachi at Sekidera. Shields has been heavily involved with Indian music and dance during the past decade, but here she has set the words of a Noh play for soprano, alto flute, and koto in a style that sounds (to my semi-trained ears) thoroughly Japanese. Other composers, while retaining more of a “Western” framework, have nonetheless been overt in their courtship of the musical “Other.” Alan Hovanhess is certainly one of these composers; his short Allegro on a Pakistani Lute Tune is part of CRI’s reissue of Robert Helps’s landmark 1966 recording New Music for the Piano. Peter Garland has been a lifelong student of Native American musical traditions, and has lived in both Mexicos (the old and the New). His Dancing on Waterfor clarinet and marimbas is based on a fragment of a Mexican folk tune.

The line between “Self” and “Other,” culturally speaking, can get blurry, however, particularly in America during the last hundred years. “The total musical culture of Planet Earth is ‘coming together,'” George Crumb wrote in a 1980 essay. “Numerous recordings of non-Western music are readily available, and live performances by touring groups can be heard even in our smaller cities.” In his Music for a Summer Evening, Crumb draws in some obvious ways from the music of different cultures – Tibetan prayer stones, African thumb pianos, and a ‘guidaja del asino’ form part of the percussion – but it is harder to apply to this music the same “exotic” description that you would apply to Sidney Bechet and John Reid’s Egyptian Fantasy (which, despite the sinuous clarinet line, is nothing more than a tango, after all).

Two composers I don’t normally associate with “world music” are Libby Larsen and John Harbison. Life is full of surprises, however, and Larsen’s Marimba Concerto: After Hampton is one of them. The Hampton in question is, of course, Lionel, and in each of the three movements Larsen tries to present the marimba in a different way. The last movement takes account of the marimba’s role as percussion ensemble member in many non-Western cultures. Harbison’s San Antonio for alto sax and piano depicts a Spanish fiesta stumbled upon by a traveler on a sultry August afternoon.

Sidney Bechet isn’t the only jazz composer this month who has flirted with a world music tradition. The rhythms of Mel Graves’s music betray not only the influence of “odd time-signature jazz” but also African, Indian, and Brazilian jazz traditions. Rent Romus’s tribute to Albert Ayler includes his own Snow Ghost, written for a show dedicated to music of the Finno-Ugric tradition; Romus feels that the piece bows to Ayler’s use of “world folk music concepts.” Fred Bouchard has written that Mike Nock’s Nata Lagal reminds him of Duke Ellington’s arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s “Arab Dance.” Naturally, Tchaikovsky’s “Arab Dance” was probably much more a reflection of his own world than that of the culture he was portraying…we can look down our nose at that, but then what do you say about The Rumba Club, a group of contemporary New Yorkers – white, black, and Hispanic – turning Cole Porter’s “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” into a bolero? They’ve taken the imperialist attitude that is implied in pieces like the “Arab Dance” and turned it upside-down, with delightful results. (I have no idea whether this was intentional on their part, and so I should add that the disc is replete with great original material, as well.) If you still like your Porter straight up, however, you can listen to the reissue of the same tune, originally recorded by Maxine Sullivan and Teddy Wilson in 1944.

Next, there is a group of pieces that were inspired in some way by non-Western texts. Without a long time to study, I found it difficult to determine whether the non-Western influence extended to the music, as well. John Alden Carpenter’s Gitanjali Songs, settings of poems drawn from a large collection by Rabindranath Tagore, feature vaguely non-Western harmonies. Alex Keller’s The four hundred boys was inspired by the multiple translations and oral re-interpretations of the ancient Mayan text the Popol Vuh. The creative result was an electronic piece in which he applied repeated “translation” and “re-interpretation” to the notes of a piano performance. William Kraft’s Songs of Flowers, Bells, and Death is a meditation on the “frustration and helplessness” that accompany war. Kraft’s texts span 2600 years and five cultures.

The division between cultural “Self” and “Other” gets fuzziest in music like Michael Jon Fink’s I Hear it in the Rain. The pace of this music, so simple as to defy any sense of progression, perhaps has its spiritual roots in non-Western thought. Peter Warren and Matt Samolis’s Bowed Metal Music, for “steel cellos” betrays a similarly non-directional (in the traditional Western sense) focus on the overtones produced by sympathetically vibrating cymbals and rods. But at the same time, I have to wonder if the Western and the non-Western have become thoroughly homogenized? This kind of music has American precedents in the work of Feldman, Cage, and others. And on a mundane level, I routinely find books on “feng shui” up by the register at Barnes and Noble…

A different way of looking at the “Other” is to cross over one of the various dividing lines within our own culture. There is the male/female divide – when the barrier between the two sexes was sturdier, it was easier to idealize “Woman,” I imagine. A monument to those days gone by is provided by The Eternal Feminine – the title an ironic allusion to Goethe’s womanly ideal – which presents the work of nine women who had the temerity to cross into a man’s world. (Libby Larsen is significantly younger than her eight colleagues, but her Love after 1950 songs certainly reference the situation!) While things on the classical front have improved, the inequity between the sexes in the jazz world is still bad; ironic – and fortunate – that this month would bring us two excellent jazz discs by women: Jane Ira Bloom’s Sometimes the Magic and Roberta Piket’s speak, memory.

Then there’s the black/white divide. Going back again to my own fruitful cross-cultural forays, I remember being introduced, while a college student, to James Baldwin’s Another Country. The boo

k struck me with incredible force. One scene in particular has stuck in my mind, when Cass Silenski, a dissatisfied white married woman, escapes uptown in a cab to hear Harlem jazz. The arts (not just music) have provided a forum for frank racial discussion throughout the century. Lamentably, there is still a racial imbalance in “classical” music, and if you combine that with a gender imbalance – well, Lettie Beckon Alston is a rarity. (I feel a little guilty focusing so much on her background, so let me state plainly: listen to her electronic music – it’s good.) Ricky Ian Gordon isn’t the first white man to set Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes’s poetry to music (think Kurt Weill), but is he the best? You decide. Richard Davis, as part of his appropriately titled Homage to Diversity, takes a jazz approach to the Eccles Sonata, that staple of the intermediate bass player; it’s worth the disc. Mirta de la Torre Mulhare’s “musical re-telling” of Othello re-assigns racial roles in keeping with 21st-century America: Othello is an Irish-American senator running for governor; Desdemona is an Hispanic reporter; Cassio is a black district attorney. I found this diversity to be less apparent in the music itself.

Finally, there’s the gay/straight divide – again, I’m proud to say, something that has been less of an issue in the arts than it has been in the culture at large. David Del Tredici has found inspiration in his “out-ness;” Secret Music features three new song cycles. Many of the poems he has set are sexually overt, and some of them deal with the feeling of being the Other – not by choice – within one’s own culture.

There are just a few pieces this month that I can’t relate to the idea of the “Self” and the “Other.” In the “twentieth-century giant” department, we have Leonard Bernstein and William Schuman, who are represented by a re-release and a re-recording, respectively. A new disc of famous choral works conducted by Robert Shaw includes a short excerpt from Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms, and Naxos has just issued a new recording of Schuman’s Violin Concerto with Philip Quint as soloist.

Visitors to the American Music Center often come in search of new repertoire for unusual combinations of instruments. Two new pieces for voice and small ensemble struck me as interesting additions to any soprano’s repertoire. Roger Vogel’s The Frog, He fly…Almost is a setting of a quirky, nonsensical text for voice and trumpet. M. William Karlins’s Song for Soprano is a chromatic rendition of a poem by William Blake for soprano, alto flute, and cello. Karlins’s Quartet for Strings, which employs a soprano in the last movement, might make a nice companion piece to Schoenberg’s seminal second quartet.

Three discs this month reference German-ness in some fashion. J.K. Randall’s two-movement piano work GAP6 is subtitled one of those 2mvmt. middleBeethoven pianosonatas in E/F/F# not G. George Rochberg’s Third String Quartet contains a more easily perceivable link to Beethoven, clearly modeled as the piece was on the older composer’s Op. 132 quartet. Finally, Darkness and Light, Volume 3, part of a series of discs recorded at the Holocaust Memorial Museum, includes pieces by Robert Stern, Tom Myron, and the German émigrés Lukas Foss and Karl Weigl. The pieces on this disc, all in someway connected to the Holocaust, should serve as a reminder of the tragic consequences of demonizing the “Other.”

The Asian Connection

Iris Brooks Photo by Kevin Misevis, courtesy Iris Brooks |

As both a musician and writer I have been drawn to Asia like a magnet for many years. It is not merely the exotic sounds of the hypnotic instruments that lure me in, but a more all-pervasive aesthetic, incorporating space and grace in the sounds and intent as well as in movement, calligraphy, flower arrangements, tea ceremonies, and landscape scrolls. I am one of many Americans who has been sucked into an East-West vortex where the music (both traditional and new) of many Asian countries, acts as sustenance as well as a resource for creating something new.

Composer/performer Skip La Plante, who is also the co-founder of Music for Homemade Instruments says: “For some of us, Asian music is about as fundamental to our lives as arithmetic. As a composer I function much as a librarian. I have a large collection of instruments and knowledge of a variety of musical traditions—specifically how these traditions organize sonic events. I can take whatever I feel like off the shelf and apply it to whatever the situation is.” And yet La Plante is rarely playing traditional music verbatim; he is more interested in creating his own pieces and instruments. While he has studied Indonesian gong-making technique, he prefers suspended refrigerator vegetable bins, which sound surprisingly gong-like.

Similarly, composer Barbara Benary—who is the artistic director of the Gamelan Son of Lion ensemble, playing new American pieces on her own homemade Indonesian gamelan instruments—speaks of becoming “bimusical” (or “multimusical”) a term she borrows from ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood. This is evidenced as she casually picks up a Chinese bowed erhu to blend in a new American work for Indonesian gamelan (percussion orchestra). Composer R.I.P. Hayman who has traveled to most Asian countries and amassed an impressive collection of recordings and instruments adds that he is still digesting musical material which “arises in surprise” in his work.

In interviewing a sampling of two dozen American musicians heavily influenced by Asian musics, similarities began to emerge. I was interested in their motivation, not just what musicians are doing, but why. Regardless of the musical traditions they have pursued, most mentioned the early recordings and concerts of classical Indian music by Ravi Shankar and/or Ali Akbar Khan as their first window into Asian music. Jai Uttal was so mesmerized by an Ali Akbar Khan concert that he immediately dropped out of college to study with the master. Several musicians mentioned the impact of Asian films, such as Pather Panchali, by Indian director Satyajit Ray (with whom Ravi Shankar often collaborated) or the work of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, and one spoke of an abundance of National Geographic magazines as an early inspiration.

Not all Americans intrigued by Asia want to play traditional music(s) or use traditional techniques. Raphael Mostel does not believe music is a universal language. “Traditional musics are many languages and many dialects. What led me to create the Tibetan Singing Bowl Ensemble: New Music for Old Instruments, was the desire to compose a new kind of music, taking basic elements which all people have in common so that the music would be equally understood (or misunderstood) everywhere in the world. Truly universal.”

References to an older generation of American composers with one foot in Asia include Henry Cowell, Colin McPhee, John Cage, and Lou Harrison. Their influence was particularly felt regarding stylistic as well as philosophical ideas with new attitudes about space and time. Percussionist Glen Velez-for whom Cage wrote a 1989 composition for tambourine – recalls a visit at Cage’s house. “He told me if you look at the sky, it is a blank canvas and he asked, looking at the pinpoints of the stars, ‘why are they there?'” But the minimalist connection was also cited with LaMonte Young, Terry Riley, Phil Corner, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. Richard Teitelbaum—who has written music mixing Tibetan Buddhist chant with breath, brainwaves and synthesizer and another piece for Japanese Noh flute, saxophones and sampler – teaches a course at Bard College about the relationship of these composers to the Asian musics that influenced them. While George Harrison may be Ravi Shankar’s most famous student, other rockers also listened to and studied Indian music including Jimi Hendrix, Mickey Hart, and the Grateful Dead. In the jazz world John Coltrane, Don Ellis, Yusef Lateef, Miles Davis, and Charles Lloyd are important regarding a modal presentation and improvisation, a deconstruction of Indian music, and the role of meditation.

For some, the role of spirituality is expressed through music á la Asia. This may be manifest by adherence to a strict tradition—kirtan, devotional Hindu singing from North India and Japanese Buddhist shakuhachi flute repertoire in the Meian style, thought to represent the simplest form of blowing shakuhachi as a spiritual practice. American Krishna Das speaks of music as a doorway and sings as a devotional practice. “Chanting is a part of every spiritual path. It’s about adoration of the beloved; it’s all about love,” he explains. Others create an original hybrid form as Jai Uttal has done with his Pagan Love Orchestra, mixing a Western pop sensibility and colorful orchestration with devotional songs.

Some Americans master an Asian instrument such as Steve Gorn playing the Indian bansuri flute. Although he plays with Indian musicians where he is accepted on the concert stage in India, he also takes the instrument into new settings. He plays bansuri in a pop context with Paul Simon, in jazz with Jack DeJohnette, in world music with Simon Shaheen, and in new American music with Glen Velez. “My personal feeling is I am a Westerner and bring that background to my work. I want the Indian stuff to flourish in other contexts,” says Gorn.

Composer Lois V Vierk was drawn into the world of the Japanese court gagaku (literally elegant music) through an initial study of Japanese dance. The way the body moves and breathes was the initial pull for her, followed by the combination of strength and elegance in the music. “The hichiriki is so powerful – it’s the loudest instrument in the world per cubic centimeter,” volunteers Vierk, who was commissioned by the Lincoln Center Festival to write “Silversword” (1996), for gagaku orchestra. She is most interested and influenced by the slow unfolding of Japanese court music. “The nuances are not just decorative; they have meaning and that taught me a lot about phrasing,” she adds.

American instrumentalists also look to incorporate techniques from Asia. American players of gamelan music such as composer/clarinetist Daniel Goode incorporate repetitive elements, circular breathing, and drones into their own work. Vocalist Lisa Karrer says: “While rehearsing for The Pink, composer Tan Dun taught me the rudiments of Peking Opera style. As a result I sometimes employ those attack, sustain, and decay methods in my own vocal compositions. Likewise in my work with Javanese composer Tony Prabowa, my singing has been informed by his filigree-like vocal lines, which emerge from the traditional Javanese style.” For Karrer the impact is larger than technique. “By learning and playing this music my sense of psychological and physical time has changed and shifted.”

For percussionist Glen Velez performance practice is also about more than learning specific techniques. With Azerbajani music he heard what was appropriate with density and space—how

much to play and when not to play in an ensemble situation. “It let me see what was successful in a traditional setting and taught me about the sound values of a culture.” Composer/performer David Simons incorporates a variety of traditional techniques such as a Balinese kotekan (interlocking melodies) and gong cycles along with North Indian concepts of tala (rhythmic cycles) and tihai (rhythmic ostinati repeated three times to end on the first beat of the cycle) in his compositions. “For at least 25 years I’ve considered the combining of music cultures (East-East, East-West, and other unholy marriages) to be a frontier worth exploring, with endless possibilities. Just one example: using Indian santur technique with chopsticks on a Chinese zither tuned to an Indonesian scale playing rhythms of the Ewe tribe from Ghana West Africa.” Simons also notes that nothing takes place in a vacuum, pointing out that Asians have been migrating to the New World for centuries and culturally intermingling.

Sub-genres of pop music are a fertile place for influences going East to West and West to East such as Bangra/hip-hop Tuvan/blues and Qawwali crossover. Nowadays Americans don’t have to study Asian instruments in order to have their sounds available. Modern-day samplers and synthesizers contain patches with sounds of biwa, koto, sitar and gamelan. And while some Americans have made journeys East to soak in the culture on a visceral level accompanied by years of disciplined practice, others are instantly accessing Asia via the Internet, CD ROM, recordings, films, and MIDI patches.

As a nation of immigrants, Americans celebrate multi-culturalism. It has become as natural to play a raga on a sitar (or guitar) as a Mozart string quartet. And why not? With an ear towards Asia, musicians and composers are blending new sounds, styles, and structures in an ever-broadening and changing American sound palette. It’s part of the process of keeping American music and culture vital.

Terry Riley: Obsessed and Passionate About All Music

February 16, 2001—The Wortham Theater Center, Houston, TX

Transcribed by Julia Lu

Sections:

- Earliest Musical Experiences

- Studying Composition and Discovering Jazz

- The Birth of Minimalism and In C

- Studying Indian Music

- Solo Keyboard Improvisations

- Just Intonation

- String Quartets & Other Chamber Music

- The Orchestra vs. Intimacy

- Music Theater & a Vocal In C

Earliest Musical Experiences

FRANK J. OTERI: Terry, I am so honored and thrilled that this talk is finally happening.

TERRY RILEY: Not as honored as I am.

FRANK J. OTERI: You have been one of the greatest musical heroes in my life. I first heard In C and A Rainbow in Curved Air when I was a high school student…

TERRY RILEY: You were a high school student when it came out?

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughter] No, I was born when it came out!

TERRY RILEY: Oh [laughter]

FRANK J. OTERI: But I was a high school student when I learned that your music existed. I found your records in a rock record shop in Greenwich Village and that was a pivotal moment for me, which is why I thought it would be interesting for us to start off talking about what your early influences were in your musical education and what shaped the kinds of decisions you’ve made as a composer and as a musician growing up. You mentioned radio and hearing old standards on the radio as you were growing up in the 30s and early 40s and I thought we could talk a little bit about that for starters.

TERRY RILEY: By the time the war broke out in ’41, my father joined the Marine Corps and after that he was sort of a professional Marine and we were living up in northern California and we kind of traveled around California during the war and lived with my grandmother and stuff like that. But I was never living in a big city like San Francisco or Los Angeles. I was always out in smaller rural areas and so my music education was kind of catch as catch can. I had an uncle who played the guitar, an uncle who played the trumpet, an aunt who played the accordion and that was my contact with the music world.

FRANK J. OTERI: What was the first instrument that you played?

TERRY RILEY: Violin. I started on the violin before the war and I was actually really enjoying it and was doing pretty well on violin. But then when the war broke out we moved to Los Angeles briefly ‘cuz my father had to take military training down there before he was shipped to the Pacific. And then that was the last; I had four months to six months on the violin. I think it was very, very basic you know. I think I could play the Marine Corps hymn though for my father which made him happy!

FRANK J. OTERI: So at what point did you decide in your life that you were going to be a musician and a composer?

TERRY RILEY: Well, I think I was very young. I mean I remember just always being obsessed and passionate about music when I heard it and deeply moved by it, you know. It was the important emotional event in my life to hear music and to really feel it and I don’t know if I formalized in my thinking that I was going to be a musician, but thinking back on it, it was the only thing I really felt obsessed by.

FRANK J. OTERI: Was there any particular music that you heard that you were more interested in than other music or was it everything?

TERRY RILEY: Uh, you know it was pretty much everything. When you’re young, like every new impression, any musical impression is a whole new universe, world and galaxy that comes into your life. So as it came in one by one I was tremendously excited to hear anything that I hadn’t heard before. As I said, in the beginning it was whatever was coming over the radio and at that time it was commercial radio. So mainly standards that you would hear…

FRANK J. OTERI: So when was the first time you heard western classical music?

TERRY RILEY: I think I was eight or nine when I started hearing occasional pieces of western classical music and around that time also my mother found a piano teacher for me because I had been playing a lot by ear and she thought I should, since I liked it so much, every time I’d go to someone’s house that had a piano I’d sit down and spend the time there at the piano. So they got me a piano and a piano teacher and she started introducing me to little pieces of Bach. And that was my first contact with western classical music.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now in your formative years growing up, did you ever think of there being a division between classical and popular music or was it all part of one?

TERRY RILEY: Never. I don’t think at the beginning especially not, but as I got older of course you know, then. By the time I got to high school I got the first really good music teacher that I’d ever had. I’d go to his house in the afternoon after classes and he’d play me all these really wonderful records in his collection and I was starting to hear for the first time Bartók and Stravinsky and other things of 20th century music and that was my last year of high school/first year of college.

FRANK J. OTERI: And at this point had you started writing your own music?

TERRY RILEY: I did a little. My teacher was writing a musical for the high school to perform. And he asked me to write one of the songs for it. So I think that was my first composition. I wrote a popular song for this musical.

FRANK J. OTERI: Do you still have that music anywhere or is it gone?

TERRY RILEY: I don’t have the music. I kind of remember it, but I don’t have it. Whatever was written down is gone.

Studying Composition and Discovering Jazz

FRANK J. OTERI: Now when you studied music formally at the university level, I know I heard this from La Monte Young when we all had dinner together, that you, La Monte, and David Del Tredici were all in a composition class together. What an exciting composition class that must have been! What sort of things were you writing at that point?

TERRY RILEY: The period you’re talking about is I think around 1960, ’61 in the UC Berkeley composition class. Around that time, I had gotten very interested in serial music, especially the piano music of Schoenberg, which I liked very much. I found this complete freedom, rhythmic freedom that I hadn’t experienced in other composers before and I wanted to experiment with that myself. So around that time, I was writing a set of piano pieces that were very much influenced by Schoenberg and yet when you look at them now, they’re still fairly tonal. They hold very close to certain centers and I didn’t use a tone row.

FRANK J. OTERI: Do you still acknowledge those pieces. If someone were interested in playing them, would you release them?

TERRY RILEY: Yes. I guess I would say from about those pieces I would say was my beginning. I wrote some pieces that I would still acknowledge before that, but unfortunately they’ve been lost in my moving around. I wrote some pieces, you know when I was at undergraduate school. A trio for clarinet, piano and violin which I liked very much, but…

FRANK J. OTERI: and it’s gone…

TERRY RILEY: …I can’t find it anywhere.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now, you were doing things you were influenced by Schoenberg and of course this was the same time that John Cage was doing a lot of his experiments with chance music and indeterminacy and also it was also this great decade for jazz. When did you start getting interested in jazz and improvisation? When did that really take hold?

TERRY RILEY: Uh, I’d say that my interest in jazz really took hold with the period of the Miles Davis Quintet, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane. This emergence in the late 50s and early 60s. It’s around that same time that I was going to UC Berkeley and also a lot due to La Monte because La Monte was a jazz musician and had been playing a lot in L.A. with lots of musicians. And he introduced me to a lot. He introduced me to Coltrane. I listened to Coltrane’s music for the first time.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now did you first meet La Monte in a composition class?

TERRY RILEY: Yeah.

The Birth of Minimalism and In C

FRANK J. OTERI: When you look toward the beginning of this thing that we now look back on and say “this is the birth of minimalism” it’s sort of hard to say who started what and who was really the originator. Most people acknowledge La Monte Young as the founder of minimalism. But certainly in terms of the use of repetition in music rather than the use of sustained notes, it’s really hard to find earlier examples than the examples of your early music. When you first started creating music based on the repetition of small melodic cells, what was the initial name for what you were doing? Did you feel there was any precedent for it?

TERRY RILEY: Naming it never, never entered my mind at that time. It was just something I was doing and that other people were doing. You know La Monte and I did a lot of improvising together around this period too because we were not only at UC Berkeley, we would grab a practice room with two pianos and play for hours together. And then we would go up to Anna Halprin‘s studio and improvise more freely with whatever she had in her studio, a piano or she had various percussion instruments… La Monte had this fascination with making friction sounds and we ended up doing the two sounds piece on marimbas. We spent a lot of time playing together and improvising together, but never thinking about for instance “is this a kind of music” or “is there something this should be called?” Uh, I think that came later. But I must say I think La Monte is the fountainhead of this modern music period that’s called minimalism in the sense that he defined very clearly in his mind and in his work as a very young man, the kind of space that minimalism holds. First of all you have this space, then it’s filled with something. Well La Monte filled it with long tones and he also worked with repetition like the Henry Flynt piece, I can’t remember the number.

FRANK J. OTERI: 1698.

TERRY RILEY: Whatever. This was a piece of repetition. He was definitely exploring a lot of ways, but his main focus since I’ve known him and I think it’s been an obsession with him is to make pieces based on long frequencies that can be experienced over long durations, especially his work with just intonation where this was a very important element. So in that sense, I’d say that it begins there.

FRANK J. OTERI: I think it might have been David Lang who said that for him and many younger composers, In C was what The Rite of Spring was for most composers in the first half of the Twentieth Century. This was the great liberating piece. And in 1964, when In C was written, whether your were practicing serialism or practicing indeterminacy–the last thing a cutting-edge composer wanted to reference was tonality. By calling a piece In C, you were proclaiming the work’s tonality and tonal center. What were the initial reactions to this piece in terms of other composers of the time who had heard it?

TERRY RILEY: Well you know In C was written in San Francisco in ’64. I had just come back. I’ll just give you a little background. I had just come back from Europe after spending two years there, so my main contact was with people like Ken Dewey who is a playwright. I was involved in theater with him and street theater. And I’d moved away from any world that had considerations for such things as atonality vs. tonality, or uptown vs. downtown or whatever. They weren’t even concerns of mine any more. I was very interested in just the little world that I inhabited at that time. So, when I came back to San Francisco, I’d had this idea about really wanting to write a piece because I worked with Chet Baker over in Europe and really had this chance to experience working with a real jazz musician for the first time. And the immediacy of that kind of music and also Chet was a wonderfully lyric and tonal, and thought in these terms. He was making mainstream jazz music.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

TERRY RILEY: So, I wanted to bring that into my music too. And also at time I’d been visiting Morocco and I was getting into their music. And that also was tonal. And had a lot to do with tradition, which I was starting to get interested in, musical traditions of other cultures in the world. But when I got back to San Francisco, I didn’t appear to me, I mean it really was an inspiration. I mean it wasn’t the piece that I thought I was going to write. This came to me all as a kind of vision so when I showed it to people, like musicians around San Francisco, there was general excitement but there was also a kind of wondering how it was going to work. And, you know, putting together the performance was a bit of a mystery. In C really was these formations of patterns that were kind of flying together. That’s how it came to me. It was like this kind of cosmic vision of patterns that were gradually transforming and changing. And I think the principal contribution to minimalism was this concept, it wasn’t just one pattern, it was this idea that patterns could be staggered and their composite forms became another kind of music.

FRANK J. OTERI: What I find so interesting about a piece like In C though is that it’s so much about the performers as well. You have these 53 cells, but the performers determine how many times they play them and how many times they’ll overlap. So, in a sense, it’s a natural outgrowth of Cage’s development of an indeterminate music, becuase there really is some chance involved with this. And it really allows the players the freedom to express themselves, to decide for themselves when to go on to the next measure and to create these multiple layers. It’s almost as if the musicians all have to listen to each other to hear… They’re creating the counterpoint to some extent.

TERRY RILEY: Right. That was a big concern of mine. And also, I didn’t want to have a conductor or someone who was telling the musicians what to do. I wanted them making their decisions based on their listening. Unfortunately, it’s hard to play as a large group like that and stay together. Those were th

e problems we were encountering when we first rehearsed, how to stay together.

FRANK J. OTERI: And that’s how eventually it was performed with the pulse. How did that come about?

TERRY RILEY: As you know, and this story’s been told. Steve Reich, who was in the group in the first performance, one day said “This isn’t working!” ‘Cuz we were all playing and couldn’t right in the groove with it. So uh, Jeannie Brecken, who was, I guess, Steve’s girlfriend at the time, starting playing on the top Cs of the piano and it just immediately helped the group immensely to focus and to stay together. And it became part of the piece.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now you’ve written other pieces like In C that don’t have the pulse, that are coming from the same basic idea. I’m thinking of the piece Olson III which is also based on cellular patterns…

TERRY RILEY: Well Olson III is a pulse piece, I mean, you know its, the whole thing is pulse because it only has eighth notes in it. It only has one note value. So it didn’t have the problems that In C had being that In C is polymetric. You have different meters going on simultaneously. It presents more problems of staying locked together. But Olson III has no meters. Essentially, they’re just all eighth notes even though the patterns are different lengths. There’s never any different note values that would create a little confusion about where the beat is.

FRANK J. OTERI: The pieces that you developed subsequently to that, I’m thinking of pieces like A Rainbow in Curved Air and the various incarnations of Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band some of which last all night… Works that you had done with the time lag accumulator, basically allowed you to play In C-type pieces by yourself. They allowed you to have these cells, to throw them out there and they would keep repeating.

TERRY RILEY: Right. You could make fields of patterns again, but they came out, you know they were governed then by mechanical means of delay through tape manipulation.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now, Poppy Nogood you did on saxophone. You don’t really play saxophone anymore…

TERRY RILEY: I haven’t played saxophone since I started studying voice in Indian classical music.

Studying Indian Music

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, let’s talk about Indian classical music for a bit. You had three records out on Columbia Masterworks, In C, and then A Rainbow in Curved Air and then Church of Anthrax, the record you did with John Cale had come out. And, at that time, because of these records, you were in a way the most widely known minimalist composer, certainly much more visible than other people doing this music, although the term minimalism really wasn’t being used yet. But then, there was a period, I guess from about 1970 to 1980, when you stopped making records for Columbia and went off to study Indian music, which western composers would say is the opposite of a career path. You became a student again and, and it’s wonderful. But it’s the kind of humility that we rarely would see in somebody who was that successful at that time. What prompted those decisions?

TERRY RILEY: Well I think that there were two things involved. Uh, first of all, I met Pandit Pran Nath, that’s the main thing that prompted my decision. And I felt this immediate connection to him and his music that I had no control over. I was drawn to it. The other thing is that for me the late period of the 60s in New York when I was doing the recordings had reached a kind of point of completion.

FRANK J. OTERI: So, were they asking you for more recordings?

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, I had a contract you know to complete more recordings, unfortunately I didn’t complete it for another 10 years. They kept sending me notices to show up at the studio and I’d be in India or some place. You know I’d just forget about it. But, you know the thing is that I felt it was a good time, things had happened pretty fast you know with these pieces like In C, Rainbow, Poppy Nogood and I felt this was a good basis of work for me. And the next step for me was to learn more about how the modality of music works. And there’s no better place than India. ‘Cuz it’s a really old tradition. Plus the rhythmic complexity of Indian music fascinated me. So there were two things I really was interested in developing in myself. And I felt I could spend a lifetime trying to find these things out on my own, but here’s a person that knows it all. And why not try to absorb it through his teaching?

FRANK J. OTERI: Well certainly just as much as you and La Monte Young spawned this genre of music called minimalism which effected the entire classical music world, the work that you did also spawned a whole generation of rock musicians. The whole genre of psychedelic rock to a good extent comes out of the work that you were both doing in the earlier 60s, what wound up happening in the later 60s in rock music. But I think it’s fair to say at this point in the year 2001, you both also spawned yet another tradition. There are now so many American musicians who are playing non-European classical musics, which 40 years ago would have been unthinkable, but we now have American soloists who are not from India playing the sarod and the sitar, and Americans playing shakuhachi or playing in gamelan orchestras. And, and it raises some interesting questions about what is traditional and what makes somebody who is not from that tradition come to that tradition. And a lot of these players are fantastic, but it’s hard to book them for concerts because since they’re not of that tradition, audiences might not assume they’re as authentic. What has been your experience playing Indian music as a westerner?

TERRY RILEY: Well, you know one of the really great things about Pandit Pran Nath was he was able to give us an immediate kind of foundation for this kind of music. He was a great teacher. And he also had a very, very unique position in Indian classical music in that he himself synthesized several different styles. And he was a person that many people looked to for these rare compositions that he had gotten from many of the masters who have since passed on. So we were really lucky to receive from him some teachings that were quite rare and which some of the people in India didn’t have the opportunity to learn. So when we go back to India now and perform, I think we’re quite well appreciated. They especially like to hear some of these rare works that he was teaching us and that now are gone except for some of us Westerners who have managed to learn them from him.

FRANK J. OTERI: Did Pran Nath have Indian disciples as well?

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, but few. Most of his Indian disciples didn’t turn out to be professional musicians. There were only a few. A lot of them were people who loved his music, but they just did it for themselves. They didn’t do it professionally… For the last eight years, I’ve gone to India every winter with a group of students from the United States and some from Europe who have been interested in learning this music of Pandit Pran Nath. Pandit Pran Nath was alive until ’96 and was teaching this class for the first four years. And after he passed on, we continued to take these students over every year. In fact they’re going this year too.

FRANK J. OTERI: That’s right, they’re there right now.

TERRY RILEY: Well, they leave on the 21st I think of February to go. So this has been a really good connection for Americans who are interested in studying Indian classical music because a lot of the people from his tradition are in India, and join our group so we all work together and give concerts and there’s a lot of interaction and we perform for each other.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now at this point, do you have Indian students who are studying music from you or studying these ragas of Pran Nath’s?

TERRY RILEY: Occasionally I will, but most of my students are Western.

FRANK J. OTERI: Because you’re based here most of the year.

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, but you know there’s no reason an American can’t… It’s like jazz, you know, some people say things like only a black man can play jazz. Actually, if you can do it, you can do it. And God knows, why a person can do it if they can.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, as I like to say when people raise the question of authenticity, I say we

ll you have no problems with an American string quartet playing Beethoven. All of the world’s music belongs to the whole world.

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, and you know there’s a tremendous amount of hard work that goes behind all of this too. It isn’t that we just took one or two lessons and went out and started singing raga. I mean that’s thirty years of work and long hours of practice and study. So eventually something has to come out.

Solo Keyboard Improvisations

FRANK J. OTERI: Right. Now at the same time that you were studying raga, you were doing a lot of solo keyboard improvisations and I believe around this time you started working with just intonation scales. I’m thinking now of Descending Moonshine Dervishes, and then Shri Camel which was the record that finally fulfilled the Columbia Masterworks contract which I’m so glad finally came out because it’s one of my favorite records of yours. And it was so interesting hearing raga one night followed by solo keyboard from you here in Houston this week. How do you feel these two streams of your music have influenced each other?

TERRY RILEY: Well I don’t think there’s an awful lot of influence coming from my Western music roots or my own compositional roots, although I will say that sometimes when I’m singing raga I do feel that I get into a different kind of feeling than just purely Indian tradition. And I think it has to do possibly with phrasing that maybe is coming more from jazz, some combinational. But there’s so much in Indian music. It’s such a large tradition that it’s hard to find anything in it that you do that isn’t related to it, except for say complex chord changes which they don’t have. And you don’t do this in raga any way.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right, but certainly your keyboard music definitely is informed by your study of raga. And I guess that’s where you add the complex chord progressions to the raga-like melodies.

TERRY RILEY: With the keyboard music I feel it’s kind of an anything goes palate. Especially since I improvise a lot, whatever I’m hearing at the time, I like to try to pursue. You know, follow in a spontaneous way. There’s definitely, you know the study of Indian music and all the tetrachords that make up the raga, all the different little tonal modules that make up the ragas are, are so pregnant with feeling and emotion that as you’re playing you’ll suddenly be starting to hear one of these and then it’ll start dominating the improvisation that this particular modal flavor will become the dominant mood. So it’s a powerful influence on anything I do on the keyboard.

Just Intonation

FRANK J. OTERI: Now the decision to retune the piano into just intonation. At first you were doing it with electric keyboards, but then later you played on a retuned acoustic piano. I’m thinking of my favorite solo piano recording of yours, The Harp of New Albion. What prompted the decision to work in just intonation? Was that also derived from working with La Monte and talking to La Monte?

TERRY RILEY: Of course The Well Tuned Piano is a real monument in just intonation piano, and was beckoning me to also work in this way. The piano becomes a totally different instrument when you retune it. You know it doesn’t sound like the European piano. It becomes a much more pure instrument. The overtones start reinforcing themselves, each other. And you start getting a different timbre out of the piano. So it’s a real temptation to retune the piano to create music. Plus, when you have a tuning you actually have a piece. If you retune the piano, that tuning actually will create a piece. So you’d have as many times as you’ll retune it, you’ll have that many pieces. You know, and you just have to change intervals slightly in it to create a different color in the piano. I’m sure it’s something that will be explored more and more in the future. The only problem is that pianos are quite tedious to retune and to stabilize. It takes many days of tuning. So it’s labor intensive and it drives a lot people away from trying it. Plus it’s hard to find a venue that will let you take a piano for three or four days and just hold it there in that tuning because usually there’s demand for other people to use it.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right, so now when you tour you mostly play pianos in twelve equal.

TERRY RILEY: Especially if I’m doing one nighters. You know.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right

TERRY RILEY: If I’m going here to there there’s just no time to do it. It has to be set up so that you have several days in the place where you’re going to play the retuned piano.

String Quartets & Other Chamber Music

FRANK J. OTERI: I would dare say you spawned yet another thing in contemporary music when the Kronos Quartet asked you to write a string quartet for them. Before that happened I think a lot of composers were really ignoring the string quartet. And since that’s happened, the string quartet is so alive and now there are quartets all over the country and all over the world playing new music in a variety of styles and to some extent I think that the collaboration with Kronos in the mid-80s is responsible for that. What prompted you to write music for them after years of not writing music for other people?

TERRY RILEY: Well, as you know, I didn’t write any music down in the 70s, that was a period where I was in a non-notational mood so when David Harrington came to Mills College where I was teaching, he started talking to me right away about writing a string quartet. Now I love string quartets. I’d written one in college, and Bartók… At one time I sat and listened to Bartók string quartets for hours on end just because I loved those pieces of his so much. And so it wasn’t really hard, I didn’t resist it too much when he suggested writing a string quartet. It was a little hard for me to get warmed up to writing music again because I’d gotten into this totally non-notational frame of mind. I saw music as a spontaneous sonic event that had no paper and pencil involved at all.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now since you’ve written those string quartets, and you’ve written quite a few at this point, you’ve also written for a number of other ensembles, I’m thinking most notably of the wonderful work you did with the Rova Saxophone Quartet. In some ways the saxophone quartet is a wind equivalent of a string quartet in that you have the same sonority translated across a range of instruments. Are there any other ensembles that you like writing for as well as this point?

TERRY RILEY: Well I’ve written for Zeitgeist who I enjoyed working with. A lot of times I’ll write just because of the musicians. You know, not necessarily that they’re playing any particular instrument but the musicians themselves seem to be the kind of people that I think would be really devoted to the kind of thing I write. And that’s what it requires for a really good collaboration. Since I played saxophone, I ended up writing a lot of saxophone quartets, you know I’ve written a couple since the Rova and I’m writing one right now.

The Orchestra vs. Intimacy

FRANK J. OTERI: You haven’t written much music for orchestra. Certainly in today’s society, the orchestra is not really a medium that’s amenable to personal contact. Often times you’ll get two or three rehearsals and that’ll be the end of it. There’ll be one performance and that’ll be the piece. It’s a shame though, because I know I heard a piece that you did for the Brooklyn Philharmonic which I thought was fantastic. And I thought: “Wow I’d love to hear more Terry Riley orchestral music.” How can composers create music for large ensembles at this point in time and maintain that personal contact which I think is so crucial to the success of your music, but the success of so much other music as well?

TERRY RILEY: Well, if you have someone you can collaborate with, if I had a conductor who said: “I’ll put the same amount of work into your orchestral music as Kronos put in the string quartets.” That would be a good starting point, but that’s economically unfeasible today, conductors can’t usually commit too much time. Occasionally, there’ll be some work that they’ll devote a lot of time to. But everything I’ve done… I’ve done three pieces for full orchestra and a couple of string orchestra pieces and they’ve all been under-rehearsed, I mean really under-rehearsed and except for I’d say my string quartet concerto, The Sands which the Kronos had played…

FRANK J. OTERI: That’s a great piece.

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, that got rehearsed more and that’s what it takes. I think the other problem is the kind of things I like to happen in music I think work best with lighter forces because it’s more mobile and rhythms can shift faster and there’s more clarity. Orchestras are fairly ponderous and it’s sometimes hard to get some of these really active shifts in tempo and things that I like to get and have them be clear. You know, have them be able to play with the clarity of a small jazz ensemble or something.

FRANK J. OTERI: You’ve also improvised music with other players, both Western musicians and musicians of other traditions. You mentioned Krishna Bhatt earlier this week. How do you perceive the difference as a composer looking at a work where you’re collaborating with others, playing music with others, versus when you’re writing a piece of music for others?

TERRY RILEY: Well, again there we have to have a lot of time to rehearse together. Krishna Bhatt and I have really spent a lot of time sitting together doing music. Both traditional raga and some so-called fusion-type things which evolve from Western musical principles. So that to me the main element is just hanging out with the person so long that you start thinking alike.

Music Theater & a Vocal In C

FRANK J. OTERI: You actively perform. You tour around the world. You write music for other people. You also are still studying music. You’re still listening. You’re still paying attention to so much stuff that’s going on. What do you want to do next? What do you feel you would like to accomplish at this point?

TERRY RILEY: Well, I think one of things that I’m kind of interested in going back and working in more is the theatrical kind of situations for music which I really enjoy a lot. I did this little opera a few years ago called The Saint Adolf Ring which was a very small chamber opera. There were only three of us on stage. It involved videos and some very elaborate stage sets and I enjoy that very much because it made me think about music in different terms because of the theatricality of it. I’m not interested in really big operas, but I am interested in working more… I just did the music for a Michael McClure play, the poet Michael McClure, called Josephine the Mouse Singer and I found it really stimulates my imagination a lot to, to write for the stage. I get ideas very quickly and it seems to be a very spontaneous way to work.

FRANK J. OTERI: And the singing that comes out of that, is that informed by your own singing as well?

TERRY RILEY: Yeah, like for The Saint Adolf Ring for instance, the singing in it was somewhere in between jazz and Indian music. Because Woelfli, the person this opera was about, is German, I also tried to do some singing in Swiss Deutsch which he wrote in. And also, he was schizophrenic so he wrote in languages that don’t really exist. I mean he wrote kind of nonsense words and I set those and then I sang them in kind of a German, but not operatic, but you know folk music style.

FRANK J. OTERI: So in terms of the kind of singers you would want to work with on this, the standard operatic bel canto singing used for Verdi and Puccini doesn’t really work with this.

TERRY RILEY: Well, it could. I would like to see for theater works a mixture of singers. So that some might be bel canto, but then you might have a singer with no vibrato I mean from an Indian style or a jazz scat singer. I would like to have a theater piece that would mix singing styles. I think there’s places and of course there’s different approaches to bel canto singing too. There are some Western musicians who have very, very fine control on their vibrato so that they’re not just doing it indiscriminately.

FRANK J. OTERI: In the performance of In C that you’re doing with the Bang On A Can All-Stars tonight, you’re singing with them. It sort of brings our talk full circle because I’m hearing things in In C that I never heard before hearing you sing it. I’m hearing connections to much older modal music traditions than I ever heard in it before. Is that part of the reason why you’re performing it this way tonight?

TERRY RILEY: In recent performances of In C, I’ve been singing more and more and not only me, but I’ve brought in other singers too and I think the vocal aspect of this is a good addition to it. And it probably, as you said, gives the setting of In C a different context. You start listening to it as maybe part of old music, or part of Renaissance music. I think the voice always adds some kind of humanizing quality to it.

American Music in the New World Order

Frank J. Oteri Photo by Melissa Richard |

Living in an ethnically diverse environment, I continue to be utterly bewildered by the notion that the culture of the United States should be considered part of Western civilization. Such a notion, aside from being limited and completely biased against America’s very sizable population of people from non-European backgrounds, is patently untrue. The strength of America’s culture is that it is an amalgam of European, African, Asian, Latin American, Pacific and pre-Columbian native-American cultures (did I miss anybody?). American culture’s resultant diversity and its ongoing openness to outside influences is a source of inspiration to the rest of the world.

The reality of this position is often hard to perceive within the “classical music community,” which continues to marginalize the work of American composers and all but ignore the fact that there are other classical music traditions in the world besides the one that evolved in Europe over the past 800 years; in fact, several of these traditions are even older. The classical music world finds it perfectly natural that string quartet players raised in Ohio play programs of nothing but music by Beethoven and Mozart (both Austrian composers from long before anyone now living was alive), whereas an Ann Arbor-born player of the North Indian sarangi playing evening ragas or a Bostonian playing traditional repertoire on the Zimbabwean mbira dza vadzimu might be considered somewhat suspect if not inauthentic.

A decade ago, the father of the current resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue spoke frequently about the emergence of a “new world order” to replace the stalemate of opposing superpowers. Around the same time, from my vantage point both as a listener and a composer, a “new world order” in music seemed to be emerging as well. The orthodoxies of the similarly stalemated uptown and downtown compositional superpowers (within the context of a larger classical music community that had marginalized both of them) seemed to have played itself out, and a younger generation of composers, performers and listeners had emerged for whom stylistic boundaries and cultural hegemony no longer seemed relevant. To their credit, downtown experimentalists, from Cowell and Cage on through the minimalists, had embraced many forms of non-western music as an influence, but for most it was still just an influence rather than a direct lineage, that lineage being only inheritable from a European music tradition which had ironically rejected its rebellious offspring.

Among the first generation of minimalist pioneers, however, Terry Riley stands out for going even further than most of his colleagues in embracing non-western music on equal terms with western classical music, jazz, and just about any other kind of music you can think of. I spent a week with him in Houston where one night he sang traditional Indian ragas accompanied by a group of his students, another night he improvised at the piano in a realm that was equal parts jazz and French impressionism, a third night he performed his landmark In C with the Bang On A Can All-Stars, themselves a cross between a downtown new music ensemble and an alt-rock band. Inspired by my talk with Terry Riley, I asked Iris Brooks to delve into a HyperHistory of Americans who perform a variety of Asian-derived musical traditions ranging from the purely traditional to unusual new hybrids, the creation of which is only possible in a multicultural environment such as ours.

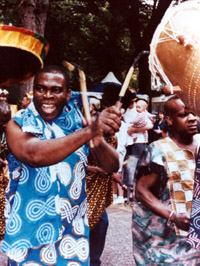

Traditional musics from around the world thrive in the United States because many leading practitioners have emigrated here. To give some perspective on the phenomenon of Americans exploring the music of other cultures, we asked Ghanaian-born master drummer and composer Obo Addy, Korean-born komongo virtuoso and composer Jin Hi Kim, Cuban-born latin-jazz saxophonist and composer Paquito D’Rivera, and North Indian sarod legend Ali Akbar Khan, who runs the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael CA, to comment on whether American-born musicians could ever hope to play the traditional music they were each born into. We’d like to know if you think there’s a difference between Americans playing European repertoire and Americans playing Asian, African, Pacific or Latin American Music.

At the dawn of the 21st century, we have the music of all times and places at our disposal. We witness the evidence of this each month in the concerts and recordings that are shared with us. It informs the news items we cover and shapes our views of what new music is, whether we are exploring recent trends among Bay Area improvisers or trying to figure out a way to make opera a viable contemporary American genre.

There is much to learn from all of the world’s musical traditions. But the most important lesson we can learn is how to appreciate our own musical traditions on equal terms with music from the rest of the rest of the world.

View from the East: Don’t Look Back

Greg Sandow Photo by Melissa Richard |

I

I’m going to talk about the extraordinary program the New York City Opera calls Showcasing American Composers, or at least about its artistic impact, though simply as an event, and as a service to composers, the thing was amazing, a word I wouldn’t use lightly. Excerpts, 40 minutes long, or so, from 11 new operas were performed with full orchestra – let me repeat that, with full orchestra – on seven afternoons in May. For that, the company and its funders deserve a medal, or maybe the Nobel Prize. It’s hard enough to get a new opera heard, and when you do, it’s usually with piano. How often do you get to hear your orchestration?

But before I get to that, I want to talk about the technique of composing operas, something I do myself, and therefore take a lot of interest in. I wanted to start by saying that writing operas is tricky, but that’s not quite right, because in some ways, it can be easier to write an opera than an instrumental piece – apart, of course, from the sheer amount of work involved, the endless details, the collaboration with a librettist, and the huge number of things that can go wrong (though sometimes blissfully right) in rehearsal and performance. But in the happy time when you’re merely composing the work, its dramatic continuity can suggests musical ideas, so you always have some sense of what’s going to come next. I find writing instrumental music harder.

And yet there’s a knack to writing operas, and, as if to prove that, many of the best-known opera composers never wrote much else: Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini, Wagner, Massenet. (Though I’d bet Rossini and Wagner could have written anything they set their minds to.) On a lower level, in the standard repertoire, come Giordano, Ponchielli, Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Cilea, Humperdinck, and others – and, at the other extreme, three top composers who wrote operas, but didn’t seem to have the knack: Haydn, Schubert, and Dvorak. In the past century, we’ve seen more composers –

it’s a nice long list: Debussy, Berg, Strauss, Janacek, Britten, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Poulenc, Henze, Louis Andriessen, John Corigliano, Stephen Paulus, William Bolcom, Phillip Glass – who’ve worked successfully in both opera and instrumental music. Maybe this is at least in part because of something that’s largely been forgotten. After Handel and before Wagner, opera and serious instrumental composition largely went down separate paths, especially in the early 19th century, when opera was called “popular” music, and symphonic works were “classical.” (This, in fact, is the origin of the term “classical music,” which came into use in the first half of the 19th century. It wasn’t used, as many people might think, to contrast composed music with folk or popular stuff, but to distinguish high-class symphonic and chamber works from the “lesser” music heard in the opera house, or at concerts by popular virtuosi.) But later on, Wagner created a revolution by writing operas with the texture of symphonic music, and the gap between opera and “serious” music got much smaller. Opera now could be musically serious, and symphonically inclined opera composers had an easier time.

And yet the old dichotomies still hold. Here in America, we’ve had opera specialists like Menotti, Douglas Moore, Robert Ward, and Carlisle Floyd, marked by a seemingly instinctive sense of theater, and then we have Copland, with far more compositional strength, whose operas sit lifeless on the stage.

So opera composition really is a special knack. Above all, if you write an opera, you have to rise to this occasion, not just once, but every time something important happens in the drama you’re setting to music. In an instrumental piece, by contrast, it’s really not a problem if one movement isn’t quite as strong as the others. In fact, it’s almost inevitable that all parts of a multi-movement piece won’t be equally strong, but that doesn’t mean your work won’t be happily performed for years, or even centuries. Does anyone think the third and fourth movements of the Eroica symphony are as striking as the first two? Does anything in the John Cage String Quartet in Four Parts match the breathtaking stasis of the third movement?

But if you write an opera, you can’t drop the ball, or at least you can’t drop it at the most important moments in the drama. In Lucia di Lammermoor, there’s one duet – between Lucia and the family priest, Raimondo, at the end of the first scene of the second act – that dips below the level of the rest of the piece. But that doesn’t matter, because the duet is dramatically irrelevant. Lucia’s brother wants her to marry someone she doesn’t love, and confronts her, at the start of Act 2, with a forged document (such a wonderful 19th-century device!), which convinces her that the man she does love is “wicked” and “cruel.” Later, toward the end of the act, she’s led like a sheep to the hated marriage contract, which, crushed and near collapse, she helplessly signs.

These two events make emotional sense exactly as they are, but between them comes

the scene with Raimondo, ostensibly so the priest can add his own persuasion (“do it for your dead mother’s sake”), but, more realistically, to give the bass who sings the largely ungrateful role something extra to do. It’s dramatically superfluous, so it doesn’t matter that Donizetti punted it; for generations, in fact, the duet has been cut from performances, and hardly anybody notices. But if the music where Lucia signs her marriage vows were weak – or, even worse, the music that caps the second act, when her not at all faithless lover suddenly appears, and accuses her of infidelity – the opera would collapse. (One reason why Verdi’s lesser operas – or Donizetti’s – don’t work so well is that crucial scenes might not have good music.)

But to see really high musical stakes in an opera, just look at Die Meistersinger, where Wagner’s story hinges on a song that – as we’re not just told, but shown, in the reactions of everyone who hears it – is just about the most beautiful music anyone has ever heard. Wagner has to write that song, of course, and how well he succeeds (not just in the beauty of the music, but in something else the story specifies, that the song is in a brand new style) is one measure of his greatness.

The song, first of all, really is uniquely beautiful, especially when you hear it in its proper context, in the third act of the opera, where, even after hours of elaborate and gorgeous music, it still sounds new and fresh. And that’s not all. The character who sings the song – Walther, an impulsive young visitor to a conservative town – improvises it, so Wagner writes music that sounds as if it’s improvised. But the song also is supposed to follow a traditional form, then break with it at one important point, and so Wagner has that challenge, too, which of course he aces.

And even then there’s more, because we hear the song three times, first when Walther improvises it for the poet and cobbler who’s his mentor, again when he repeats it for the woman he loves, and finally when he wows the whole town in a singing contest. Wagner, really flying now, makes the song much grander the third time out, as if Walther, his heart swelling with inspiration, improvised more freely when he got before his largest audience (or, more flatteringly, when he needs to make a big impression, because if he doesn’t win the contest, he can’t marry the girl). The effect is unobtrusive – you might not remember that the song had gotten fancier – but also overwhelming, as the music sweeps through a triumph that serves not just as the dramatic climax of the opera, but also as the anchor of its musical form.

Wagner tends to ground his operas in large-scale repetition, most famously in Tristan, where the huge love duet in the second act is interrupted, and then returns (or at least its music does), this time with a proper climax, as the famous Liebestod, as the opera ends. But he also does it in the Ring, where the sunburst of Brunnhilde’s awakening in the last act of Siegfried is recapitulated near the end of Gˆtterd‰mmerung, just before Siegfried dies, and thus supplies the music for a double climax (even though the two stages of the climax come in separate operas; the Ring is a gigantic structure). And in Die Meistersinger, Walther’s Prize Song forms a triple climax, bringing the piece home to the key of C major in which it began. Anyone who makes one aria carry that much weight is a great opera composer – and Wagner does it with a tune so simple (at least before it grows new branches when it’s sung the third time) that Walther could just as well whistle it, as he walks down Nuremberg’s medieval streets.

In opera, there are large and small occasions; a composer has to rise to every one. So in Pelleas et Mélisande, a single note of recitative – with a shadow falling on a melody – can turn a moment sad or fearful, In Otello, Verdi lets us know exactly when Iago makes Otello jealous, because the cellos play an E sharp, marked piano, but unmistakably a thrust of pain. (And what’s more remarkable is the timing – and the shifting emphasis – throughout this scene, which runs, with one long interruption, through most of the opera’s second act. I sang Iago once, and felt that Verdi had gone ahead of me as actor and director, composing the best possible staging of the text, and that my job was not to interpret the words myself, but to understand how Verdi had interpreted them.)

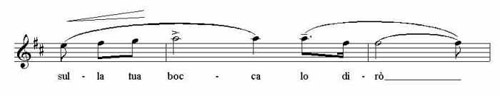

When Wozzeck sings “Wir arme Leut,” deep in the first scene of Berg’s opera, we know we’ve reached the heart of his conversation with the shallow, flighty Captain, because the music plainly bears that weight. In Philip Glass’s Satyagraha, the many repetitions of an upward scale in E bring the opera to a peaceful close. In Norma, Bellini’s troubled priestess sings just these three notes:

|

And time stops, as the strain intrigue and betrayal resolves into serenity. Not, of course, because the notes themselves are special (obviously they aren’t), but because Bellini knows how to lead up to them; because he knows how to place them in the soprano voice; (high enough to rivet our attention, but not so high that they carry any strain); and finally because the orchestra, having built up to this moment stressfully, drops out, leaving the singer, her voice framed by silence, to command the stage alone.

Which brings me to another job opera composers have to do – they have to write well for the voice. In everything I’m writing here, I’m thinking of composers’ education, and how none of this is commonly taught. There are two things involved in writing operatic vocal lines: setting words to music, and knowing what the many types of operatic voices are. Writing for the voice can be done realistically (so the words fall from the music with the natural flow of speech), or it can be stylized, as Stravinsky loved to do, and as the three Bang On A Can composers did (at least to my ear) in The Carbon Copy Building, their joint opera. I’ll talk here about realistic vocal settings, because that’s what most American opera composers write. (And also because it’s easier; each stylized vocal setting makes its own rules, but all realistic vocal writing – Webern‘s just as much as Verdi’s – seems to work more or less the same way.)

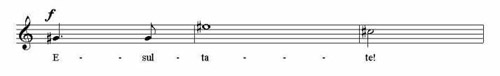

My first thought is that text doesn’t have to be set in parlando or recitative style to be realistic. It doesn’t even have to march with one note to each word; in fact, the peak of the art might be writing melodies that have their own compelling life, and yet flow as easily as speech. In Bellini’s I Puritani, the tenor’s entrance aria starts with two lines of simple Italian poetry:

A te o cara, amor talora

Mi guidò furtiva e in pianto

(O beloved, love once led me

To you secretly, and in tears.)

Bellini writes a yielding and heroic melody that stretches these words over three long bars of slow 12/8 time. Later repetitions add still more fioritura, and nobody, even in the relatively simple first statement, wou

ld speak in such a langorous, elongated way – and yet still the music perfectly preserves the normal rhythm of Italian speech. You can feel this, if first you say the words with proper stresses:

a TE o CAra, aMOR taLOra

mi guiDÒ furTIva e_in PIANto [“e” and “in” are glided together]

Then sing them to Bellini’s melody, which sets the words so naturally that you still might think you’re speaking:

|

Among current American opera composers, Dominick Argento sets words the best, I think (and I’d love to offer an example, if only I could do it without special permission), though André Previn also did it smoothly in A Streetcar Named Desire. From abroad, Britten wasn’t bad (and Purcell was wonderful) but the champions at setting English to music are – is anyone surprised? – people in pop and on Broadway. Open any collection of Gershwin, Sondheim, or Cole Porter songs, and you’ll find music that fits words as naturally as Fred Astaire dances. Or, what’s even better, not quite naturally, but with easy artifice:

The sun comes up,

I think about you.

The coffee cup,

I think about you.

I want you so,

It’s like I’m losing my mind.

This is a deceptively not-so-simple Sondheim lyric – note the extra foot in the last line – set to deceptively not-so-simple music, from Follies. There’s not an American opera composer alive, I fear, who could set these words as naturally as Sondheim does. (As an experiment, try it, then compare your version with the original. I’m disqualified, because I know the tune, but I’m sure I’d be abashed.)

And many opera composers, including some of the more famous, don’t set words so well. Listen to any new pop album; the words and music sound like they belong together. Listen to a new opera; can you really say the same thing? I’ll grant that pop composers, setting simple, rhythmic lyrics, face a softer challenge, but they rise to it; in any case most operas have relaxed moments, where setting words to music ought to be easy. Opera aspires to lofty heights; how can it reach them, if the composers writing it can’t do the simple things as readily as any kid with a garage band? (Maybe Previn sets words well in part because he’s worked in jazz.)

As for voice types, any true opera fan knows what they are – lyric soprano, spinto soprano, dramatic soprano, and so on, through all the varieties of mezzos, tenors, baritones, and basses. The categories aren’t unambiguous, they can’t define absolutely every singer’s voice, and they’re not formally codified (except in Germany). Yet everyone in the opera world understands them, and they’re essential for anyone who wants to write singable vocal music. Take the Bellini excerpt I quoted earlier; the easy top A toward the end, just touched in passing, marks this as music for a lyric tenor. A heavier tenor voice would rather sing A’s with some meat in them, as in this familiar slice of “Nessun dorma” (from Turandot) illustrates:

|

But then even the F sharps in the Bellini passage more subtly require a lyric tenor, who can phrase through them without sounding as if he’s shifted into overdrive, which a heavier voice would have to do. By contrast, Otello’s overpowering first entrance in Verdi’s opera

|

almost defines a dramatic tenor voice. A lyric voice can’t muster emphasis that low, but a heavy voice – the kind the part was written for – can all but shake the walls of an opera house.

To write operas, you need to know all this. One composer I knew in graduate school wrote a song cycle for tenor which made at least one climax around the E flat just above middle C; that’s too low for any but the heaviest tenor voice. And you’ll shoot your opera in the gut if you require violent declamation at the bottom of a soprano’s range, something only a heavy voice can easily do, and also want floating high A’s like the ones in “Mi chiamano MimÏ” (from La Bohème), which only a lighter voice can sing with the proper radiance. (To study the contrast, open a score of Turandot and compare the roles of Turandot, a vocal heavy, and LiÐ, much lighter. If you want to hear what happens when someone sings out of their proper fach, to use the German word for these categories, listen to Piero Cappuccilli, a baritone, sing Masetto’s angry aria, written for a bass, on the old Giulini recording of Mozart‘s Don Giovanni. He sings the notes, but can’t spit them out with the proper emphasis.)

I stress all this, because composers – as far as I know – aren’t taught it. That doesn’t mean that they won’t learn it on their own, but on the other hand, a year ago I gave an informal tutorial to a composer at Juilliard. He’d already written an opera, and had part of it produced, but he’d never learned the standard vocal types, or even heard of them. When we study orchestration, we learn not just the ranges of the instruments, but what flavor each part of those ranges has – we learn the power of the cellos’ A string, and how hard it is for oboes to play their bottom notes softly, as opposed to flutes. But do we ever study voices that way?