When I wrote about musicians living through the war in Ukraine for NewMusicBox and The Sampler in March, there were already fears that Russia would target artists and other intelligentsia in areas it occupies. There is a lot of historical precedent for Russia’s attempts to annihilate Ukrainian culture. Though I understood this possibility on an intellectual level, it was hard for me to truly embrace it emotionally at that time. The idea of artists being arrested and killed seemed firmly relegated to history books and dystopian fiction.

Though reports have been trickling in for months, this reality really hit home for me when I learned of the murder of Yurii Kerpatenko, the conductor of the Kherson Philharmonic Orchestra who refused to participate in a twisted propaganda concert meant to demonstrate that peaceful life had returned to the city the Russians were occupying. I was born in Kherson and I couldn’t help imagining myself in his place. Would I have fled, resisted or buckled under the pressure? Trying to learn more about Kerpatenko and Kherson’s cultural scene at large, I interviewed a number of artists who lived through months of occupation before finally fleeing. Though none of them were targeted for being artists, their stories weave a chilling narrative of survival and resistance in a region the Russians came to “liberate” from bogeymen of their own creation.

Like virtually every person in Ukraine, the artists I spoke to woke up to sounds of explosions at 5:00 a.m. on February 24th. Southern Ukraine was occupied at lightning speed by Russian troops gathered in Crimea, the Black Sea peninsula annexed by Russia in 2014. Andrii, a musician from Nova Kakhovka who prefers not to share his last name to avoid endangering relatives still left in occupation, tells me that by noon the same day the occupiers were already moving through his city. There were endless columns of tanks and other army vehicles spilling across the nearby dam and onwards towards Kherson. Until his supply of food ran out, he stayed at home monitoring the situation through various news channels and chat groups. “In the first days I felt a total disorientation; it was hard to understand what was happening around me.” He heard explosions, sometimes on the outskirts of the city, sometimes in nearby neighborhoods. “At first I was comforted by illusions of a quick end to the war or at least a de-occupation of our region, in a few days, in a week, maybe in a month.” I’m reminded of the early days of the pandemic, when we all thought it would be over in a couple of weeks, except that the residents of this tiny city could not keep out the threat moving through their streets by observing responsible social distancing rules. The threat could drop from the sky or hurl from a tank’s gun at any moment.

Two of the artists I contacted, a young couple from Kherson, came dangerously close to experiencing a missile strike directly. “When the Russian troops entered the city, they randomly shelled residential buildings,” writes Anton Kosiei, a drummer and event presenter. “Our building was hit, the section next to ours. A fire started and almost the entire section burned out. A few people couldn’t be rescued because the building was surrounded and the Russians didn’t let fire trucks through while their equipment moved by. The residents themselves were battling the flames and rescuing people under the gaze of machine guns.” Luckily, Kosiei and his girlfriend, a visual artist who works under the pseudonym Olson Olberburg, were not home when this happened. They were hiding out in an athletics school on the outskirts of the city, an island on the Dnipro River, where they spent the first two months of the occupation.

The atmosphere around Kherson was chaotic in the first days of the full-scale invasion. The residents were hearing explosions, but the Russians hadn’t yet reached the city. On the first morning of the invasion, visual artist Constantine Tereshchenko rode out on his bicycle to stock up on bottled water. “The atmosphere in the city is incredible. People try not to panic, but I feel a colossal hype. There is a feeling of intense energy, a ringing clarity. The air raid siren turns on. It’s very loud. It’s the first time I’m hearing it. It is the exact representation of what is inside each of us. The siren fills the space with anxiety.”

A painting by Constantine Tereshchenko.

Unlike some other parts of Ukraine, the Kherson region was utterly unprepared for battle, though the occupiers didn’t reach the city immediately. There was intense fighting on the main bridge linking it to the eastern bank of the Dnipro. Hearing about injured civilians brought to local schools from surrounding villages and towns, Olberburg temporarily left her hideout to join the volunteers spontaneously mobilizing to gather blood donations, clothing and supplies. Throughout Ukraine and beyond, Ukrainians have been volunteering to support the war effort with unprecedented zeal.

Kherson was fully occupied by the beginning of March. About thirty volunteer fighters in the woefully underprepared territorial defense squad were slaughtered in one of the city’s parks. Residents were not allowed to collect their bodies, many of them in pieces, for weeks. The local police and most elected officials fled before the invasion even started. Treason and active sabotage is suspected. The city descended into anarchy. Marauding began, first by local thieves and later by Russian soldiers who didn’t bring enough supplies to feed themselves. Writing in a fragmented, manic stream-of-consciousness that attempts to capture the chaos of those first weeks, Tereshchenko concludes that “what is happening is such harsh surrealism that you lose all ability to act; there’s no point.”

Another Kherson-based artist, who works under the pseudonym Marianna Tarish, attempted to escape the chaos by moving in with her parents, who have a ninth floor apartment in the same island neighborhood where Olberburg and Kosiei were hiding out in the athletics school. “Before the war, I had my own studio where I worked on my art. I practically lived there day and night. It was a very cozy place right in the center,” writes Tarish. The center quickly filled up with Russian soldiers and their tricolor flags, which Kherson residents disdainfully nicknamed “Colgate” after the toothpaste.

Tarish thought the outskirts would be safer, but before long the Russians were everywhere. She remembers a lot of enemy planes flying over the city in the first weeks of the war. “One night a rocket flew very low right over our building. I’ll probably never forget the smell of gunpowder on the balcony and its horrific whistle.” Tarish made a bed for herself in the corridor, between two walls, which made her feel safer. Two walls or not, Soviet-era concrete block apartments have not fared well against direct rocket hits.

Back in Nova Kakhovka, Andrii had neither the desire nor the required state of mind to create or listen to music. ”Everything was too stressful. I wanted to turn off the music immediately so it wouldn’t get in the way of my stressing out, though obviously this didn’t help in any way. I couldn’t read books either; it was impossible to concentrate on the meaning.” Down the river in Kherson, the drummer Anton Kosiei was stuck in a similar state of anxious waiting. ”I hoped the occupation would not last. It was scary, because there were constant battles on the outskirts. There was a feeling of uncertainty, because you didn’t know if you’ll be shot at or taken to a basement or something else. I couldn’t create music. I couldn’t even listen to it.” Since the start of the invasion, the phrase “to be taken to a basement” refers to Russian occupiers abducting and torturing civilians in makeshift prisons.

The windows of the school where Olberburg and Kosiei hid out for the first two months look out onto the Kosheva River. What would normally be a peaceful sight of natural beauty was filled with rockets and artillery barrages, with smoke and fire, as the Russians bombarded the city of Mykolaiv fifty miles away. On February 28, Olberburg painted Night Over Kosheva. “After that I couldn’t paint for a long time because my hands shook and my eyes immediately filled with tears.”

Olson Olberburg’s “Night Over Kosheva” showing fire from Russian artillery over Kosheva River.

Tarish, on the other hand, found solace in her work. During the day, she would run around looking for supplies, stocking up on food and water, covering her windows with tape so glass shards wouldn’t fly into the apartment in case the windows blew out. In the evenings, she would draw and do yoga. No longer having access to her studio, she concentrated on digital art, drawing on her tablet which she picked up shortly before the war. “I got used to the explosions, but I started smoking. I would stand on the balcony as explosions screamed and windows shook. Somewhere on the horizon, rockets launched in balls of flame, and I lit my cigarette.” Tarish started putting all her feelings into her art and this is what saved her.

Marianna Tarish working on digital art in occupied Kherson with the help of her cat.

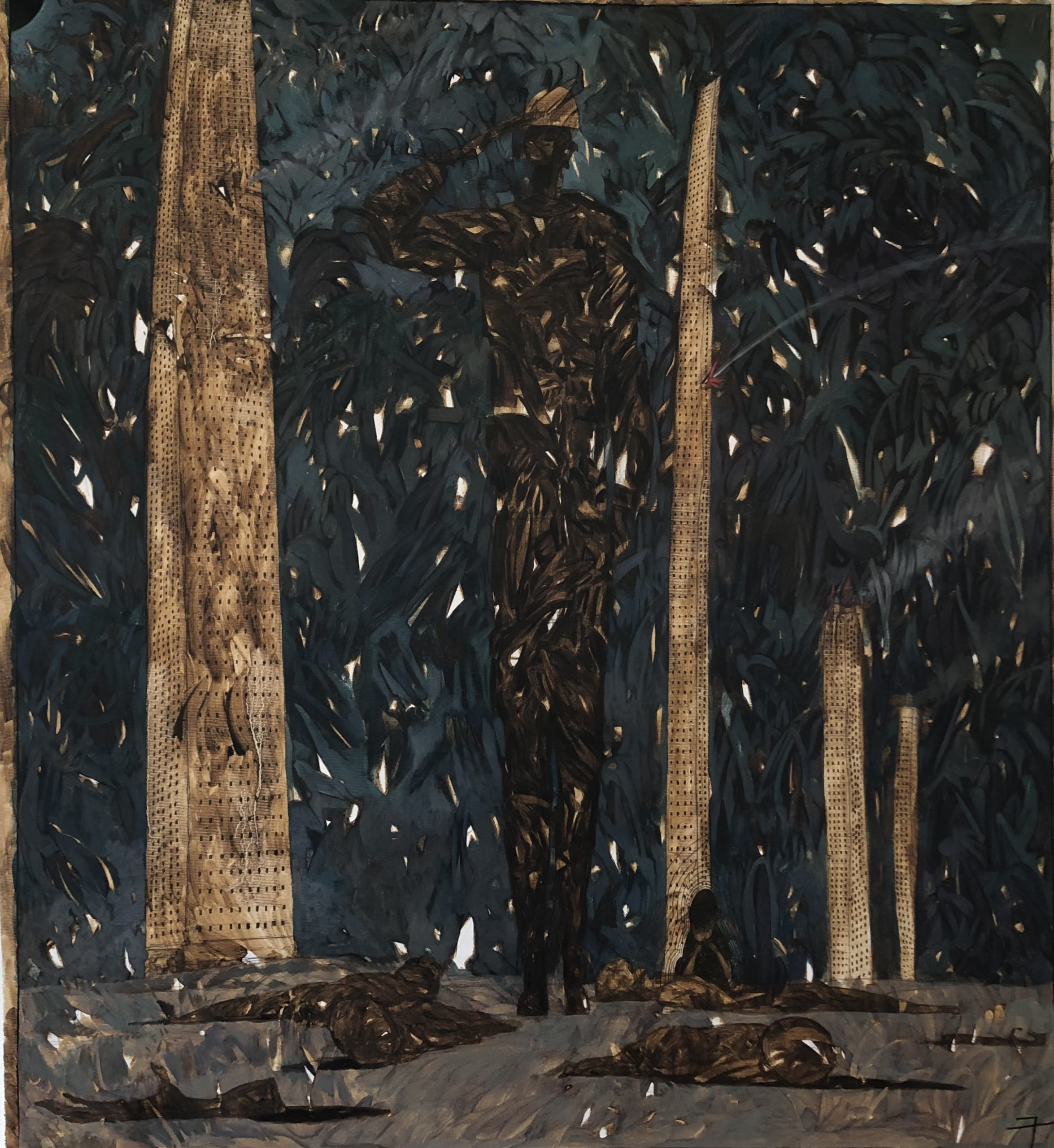

The situation at Tereshchenko’s home had its own brand of terror in those first weeks. His wife Nastia was nine months pregnant, her due date looming. There was a curfew from 8 pm to 6 am; anyone out on the streets could be shot. The ambulance didn’t come at night. “Nastia prepares to give birth at home and asks me to prepare to assist her. We both understand that birthing is one of the most sacred processes in a woman’s life. She is in a bad state. She cries a lot,” remembers Tereshchenko. “Culture is the thinnest layer of moss on the body of human existence; it was shaved off with a bulldozer; now there’s an enormous wound, blood, shit and urine.”

A few days into the invasion, Tereshchenko snapped out of his initial stupor and concentrated on his wife, trying to maintain a state of calm inside the walls of their besieged apartment. He did household chores. He polished wood. He even started to draw, “at first mechanically, by inertia, without any meaning, but this habitual activity calmed my mind and I could keep myself from being consumed.” The war receded into the background as he contemplated the horror of having to assist the birth of his child alone. A few days later, the couple made it to a maternity ward. “Nastia is on the bed screaming from the contractions. Outside the window, through the evening sky, shells fly into the city. I dance a little and sing Hare Krishna. Nastia delivers a girl, Dusia, on the 18th day of the war.” Tereshchenko’s anxiety for his daughter is all over his drawings from this time period. There are babies everywhere.

Constantine Tereshchenko’s drawings and daughter Dusia born in occupied Kherson.

After a few weeks, Nova Kakhovka, which is located on the eastern bank of the Dnipro River, ended up well behind enemy lines. Andrii could no longer hear explosions. “The streets were unusually quiet, there were few people and even less cars because of a deficit of fuel. At night the city plunged into total darkness and an even deeper silence through which you could occasionally hear the movement of [military] equipment. The atmosphere was tense and depressing.” He tried to leave the house as little as possible, moving by bicycle through backstreets to avoid encounters with Russian soldiers who had by this point thoroughly established themselves in his hometown.

Russian troops immediately started blocking supplies from Ukrainian controlled territory. There were even reports of them seizing Ukrainian humanitarian aid and distributing it to locals as their own to demonstrate their supposed benevolence. People didn’t want to take it. Grocery stores emptied out, but thankfully it was spring and the farmers markets were still supplied by the surrounding villages. Medication and cash, however, became scarce. Because of poor internet and mobile connection, Andrii’s freelance translation work dried up. Since most businesses and government institutions were forced to shut down, unemployment has been rampant throughout the region since the start of the invasion.

The situation in Kherson was similar. According to Olberburg, “when someone found out about potatoes in large bags, about pasta or onions, they immediately called everyone who needed these things, because there was a huge deficit.” Life in Kherson started to resemble the early ‘90s, the troubled years after the fall of the Soviet Union. People were selling smuggled goods from car trunks or blankets spread right on the pavement. “There were times when there wasn’t enough flour in the city and there was no bread for a week,” Olberburg continues. “I have never eaten as much bread as I did when living in occupation, and many people will tell you this.” I think about flour shortages as North Americans obsessively baked bread during the pandemic, but the intense desire for bread in occupied territories doesn’t have the same comedic ring as our collective sour dough mania. Bread has a particular cultural significance in a population partly wiped out by an artificially induced famine, holodomor, in the early 1930s.

As the weeks went by, Olberburg began to focus on the nature in front of her, to listen to birds, to meditate. “I found it very hard until I accepted death.” I feel a chill when I read this sentence, though I’ve heard this sentiment from other Ukrainians. Though this meditation on natural beauty seemed to help her mental state, the peaceful scenery rarely appears in the work she eventually started to produce. Because her hands still shook too much to hold a brush, she turned to digital collage. I scroll through her Instagram and see a radical shift in color palette; the lush greens of her fantastical pre-war landscapes are replaced by red and orange, the fluid lines by harsh juxtapositions of ruined buildings and local monuments caught in the gaze of large blue and yellow eyes. The series of digital collages titled “Look” (Podyvys’) bears witness to the destruction around her.

Olson Olberburg’s digital collages from the series Look created in occupied Kherson.

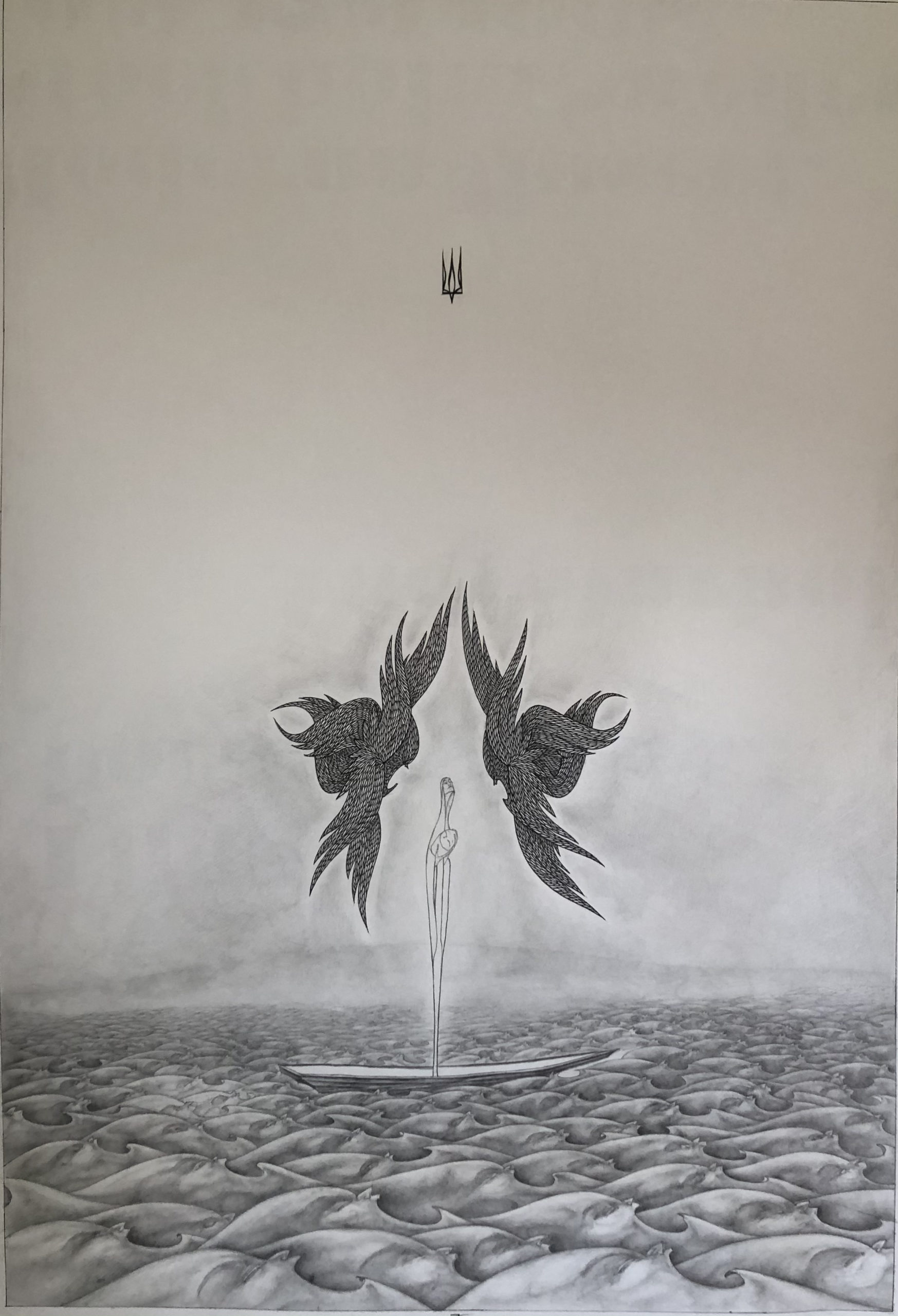

Tarish’s art went through a similar color transformation: nearly every piece created after February 24th is full of flames. The contrast between her first piece of digital art, posted to Instagram just two days before the full-scale invasion, and the first work created after is particularly striking. The pre-war Lovebirds is all blues, pinks and purples, with a warm yellow sun glowing between the two lovers. The Invaders Must Die!, appearing right beside it, shows snarling wolves wrapped in barbed wire (to represent their own slavery) snapping at a white stork that leads a sky full of souls out of the burning landscape. Tarish frequently uses symbols in her work and after the invasion, traditional Ukrainian symbols–like the stork or the red viburnum berry clusters–become especially prominent. It’s a trend I’ve observed amongst many Ukrainian artists working today, myself included. At times of existential threat, familiar symbols become important anchors not only to the past, but also to the future. They represent survival and continuity, and carry the collective feelings of the moment, just as they have for centuries.

- The Invaders Must Die

- Guardian Angel

- Red Viburnum

Marianna Tarish’s digital art created in occupied Kherson.

Eventually, the musicians also returned to work, though in private. “I could practice music in my studio, but was only able to get back to it after about two months of occupation,” writes Kosiei. He didn’t create anything new, but practiced drums. “I had to force myself so I wouldn’t lose my form. I didn’t feel like it.” When asked if his experience in the war changed his relationship to music, he muses that his playing has become “more authentic, because the war exposes you; a person can’t be anything other than themselves. I hope to retain this feeling as long as possible.” Just months before the invasion, Kosiei and his colleagues opened a new cultural space in the center of the city. Linza, which hosted a hodgepodge of concerts, theater plays, lectures and dance parties, has been shuttered since February. Continuing any public cultural activities would have attracted life-threatening attention from the occupying authorities.

After the occupiers cut off most connection to the world, Andrii in Nova Kakhovka gradually started returning to art also, watching previously downloaded movies, listening to music and reading books, but this didn’t happen until May or June, not too long before he finally fled. “Because of an absence of distractions (I couldn’t work, most of my friends had left, the atmosphere in the city was not inviting), it became possible to work on music, to finish old projects and even to create a little new stuff. Most of the time it was relatively quiet, so nothing interrupted me. The hardest thing was to get over the initial stupor, to push myself out of catatonia.”

Together with another musician working under the pseudonym Starless, Andrii released a two-track EP, Dark Corner, which documents their internal state. “The concomitant initial physical and psychological shock and pressure alternately transformed into either despair and frustration or bursts of anger and rage,” reads the album description. Andrii’s track, released under the pseudonym Kojoohar, is a harsh and bleak electronic landscape rocked by uncomfortably slow bursts that disintegrate into digital debris. It feels like something terrible happening in slow motion.

The EP’s aesthetic is not far from Starless and Kojoohar’s usual projects such as Kadaitcha, which another musician, Edward Sol, described to me as “the most famous industrial band in Ukraine.” Still, amidst the apocalyptic walls of noise, Kadaitcha explores melody, as well as moments of brightness and near tenderness, elements entirely absent from Dark Corner.

Throughout March the residents of Kherson came out to the street to protest against the invaders. The videos posted to social media are stunning. Months later, rewatching them still brings tears of pride and horror to my eyes. Unarmed civilians draped in Ukrainian flags face armed soldiers and heavy military equipment chanting “Kherson is Ukraine!” and “Go home! Go home!” They force armored cars to turn around. The Russians shoot into the air, but no one runs. A protester shouts “Stand your ground!” in Russian, clearly debunking the insane idea that Russian speakers in Ukraine wanted Russia to “save” them.

The occupiers expected to be welcomed as liberators in this predominantly Russian-speaking region. Contrary to oversimplified representations of Ukraine in Russia and in the West, language does not neatly correlate with political affiliation or cultural identity. “The eyeballs of these apes were popping out of their balaclavas when they heard our slogans,” writes Kosiei with many smiling emojis. Despite everything he endured, he seems to get much pleasure from the memory. “They were very confused by the fact that unarmed residents were bravely pushing against armored vehicles and soldiers with machine guns.” Similar protests happened in Nova Kakhovka and the surrounding towns and villages.

Before long, Russia brought in reinforcements to control the city. The contemporary versions of Soviet KGB, Rosgvardia and FSB are special forces designed to control civilian populations. They started dispersing protests with stun grenades and tear gas, and arrested people on mass. While the threat of bombing decreased, a largely silent terror began. The special forces began targeting activists, volunteers, cultural leaders, former Ukrainian military personnel and their families. They set up checkpoints throughout the cities and towns, where soldiers check documents and phones in search of any pro-Ukrainian leanings. Even private correspondence in Ukrainian, on any subject, is suspect. Some people started carrying decoy phones, because not having a phone is also suspect.

The Russians also check for tattoos. Any Ukrainian symbolism can land you in a basement, from which you may never return. One of Kosiei’s friends was beaten up at a checkpoint simply because he couldn’t satisfactorily explain the mere existence of his tattoos. “A lot of people were ending up in prison for their pro-Ukrainian positions, or just because they didn’t like you. A few of my friends ended up there, one for a month, another for two weeks. What was done to them there…I don’t even want to talk about it out loud,” writes Kosiei. Tarish also tells me of a young man she witnessed getting pulled off the bus at a Russian checkpoint. “I don’t know what they did to him. I hope he’s alive and healthy.” It’s been long understood by those of us watching the occupation from a distance that the horrors of Bucha will pale in comparison to what emerges when the Russians are fully pushed out of the Kherson region. They’ve had more than eight months to do what they did in Bucha for one month.

The occupiers eventually showed up at the school where Olberburg and Kosiei were hiding. “One of our mornings started with a search and this was terrifying,” writes Olberburg. “In front of you, there are seven men with pointed guns and you have no idea what they are thinking, but after Bucha and Mariupol you understand that there’s no humanity in these soldiers.” After this incident, Olberburg and Kosiei moved back to their own home in the damaged apartment building.

While terrorizing the local population into submission, the occupiers staged fake video shoots for Russian propaganda TV showing locals supposedly welcoming their presence and happily taking their humanitarian aid. “We saw the Russians filming their movies about peace,” Olberburg writes with apparent disgust. The occupiers also put on warped celebrations. It was precisely for such an occasion that they attempted to coerce the conductor Yurii Kerpatenko. In an interview with TV Rain (a Russian independent TV channel now operating out of Latvia), Terentii Shevchenko, Kerpatenko’s friend and former coworker from the Mykola Kulish Theater, said that the Russians wanted to mount a concert for Kherson’s annual Day of Music to show that peaceful life had supposedly returned to the city they were brutally occupying. They needed Kerpatenko to conduct and arrange the materials for this farcical charade. After he refused, armed men showed up at his home. When he didn’t open the door, they fired right through it with machine guns, killing him and injuring his romantic partner.

Trying to learn more about this tragic hero, a true dissident, I reached out to a Facebook acquaintance, accordionist Roman Yusipey who lives in Germany. They studied folk bayan (a type of accordion) at the same music institutions in Kherson. In the early ’90s, when Ukraine was just starting to open up to the world after the fall of the Soviet Union, Kerpatenko was already participating in international competitions. According to Yusipey, when a chandelier fell on the stage during Kerpatenko’s performance in Italy, he didn’t even stop playing. “He had a strong character.” He also took composition and theory lessons. His work for folk instrument orchestra, Autumn Poem, was often chosen by conducting students for their exams. They would ask him to get up on the podium to show them how to conduct his music properly. “I liked his manner of conducting,” remembers Yusipey. “His talent already started emerging in Kherson.” Yusipey also followed Kerpatenko to the Tchaikovsky Music Academy in Kyiv, where Kerpatenko focused on conducting and arranging after completing his performance diploma. Whenever the young conductor came back to Kherson, he would bring photocopies of new scores for his former teachers and their students, which must have been a lifeline in this small city still largely cut off from the world.

Yurii Kerpatenko conducting his own arrangements of Ukrainian folk songs with Gileya Chamber Orchestra

After graduating, Kerpatenko returned to his native Kherson. He spent a few years as music director at the drama theatre and occasionally conducted the Gileya Chamber Orchestra, a well-known ensemble in the Soviet era, which had fallen on hard times during Ukraine’s shaky transition to capitalism. Just months before the Russian invasion, Kerpatenko became the main conductor at the Kherson Philharmonic Orchestra. Though none of the other artists I interviewed knew him personally, they all knew who he was and were distressed by his death. Kosiei occasionally crossed paths with him on the stage. Tarish attended theatrical performances he conducted at the drama theater. As we look through YouTube videos of Kerpatenko’s concerts, both Yusipey and I mourn the lost potential he brought to the city. I get the sense that he was an important player in Kherson’s artistic revival.

According to Yusipey, even in their school days “Yurii was very independent. He was a well-mannered, but proud person. He never bent down before anyone.” Shevchenko also described him as “principled” in the TV Rain interview. These character traits did not help him survive the totalitarian regime the Russians attempted to set up in Kherson. According to Shevchenko, Kerpatenko was vocal about his views on the Russian occupation on social media. It was important to him to explain that Kherson residents thought of themselves as Ukrainian. It seems that Kerpatenko was always politically opinionated. Before the invasion, Yusipey “lazily” followed his Facebook debates from Germany, not getting into the details. They seemed like “storms in a puddle” to him then. I think about our own vicious controversies in the classical and new music community, and how insignificant they sometimes appear in the greater scheme of things. Now Yusipey regrets not paying more attention. One of Kerpatenko’s posts seems particularly prophetic: “Putin will destroy you physically under the pretext that someone is forbidding you to speak Russian.“ What troubling trends might I be missing in my own community or the world at large?

Yurii Kerpatenko conducting Oleksandr Gonobolin’s “Adagio and Allegro” with Gileya Chamber Orchestra

None of the artists I interviewed were targeted like Kerpatenko, though it may have just been a matter of time. A few weeks after the conductor’s murder, a well-known Kherson painter, Viacheslav Mashnytskyi, disappeared in suspicious circumstances. Friends and volunteers mounted a search after finding blood and other signs of struggle at his summer cottage. There is video evidence of his participation in the protests in March. The others fled Kherson some months earlier, when life in occupation became unbearable. Fleeing was also dangerous. There were never any green corridors out of Kherson or the surrounding region. Everyone left at their own risk. Sometimes the Russians wouldn’t let people through the countless checkpoints, keeping them on the side of the road for days or simply turning them around. People were searched and risked arrest. Some were robbed. Some died trying to reach freedom as Russians shot at civilian cars on a whim. Like my grandfather and his sister, many elderly people or those with serious health conditions couldn’t face the arduous journey. My grandfather worried that he would be shot if he needed to leave the car to relieve his bladder. Those without their own vehicles also faced prohibitive transportation costs as the trains and buses stopped running. I will never forget the agonizing weeks when my younger relatives weighed the decision to stay or go. Both options seemed horrible. My kidneys hurt from the fear I felt for them.

Tarish decided to flee after three months of occupation. The Russians had cut off Ukrainian internet and mobile service. “We ended up in an informational vacuum. We couldn’t reach each other or find out any news. To have no source of truth during the war is horrible.” Russian propaganda has worked aggressively to create the impression that Ukraine had abandoned the occupied territories, that their presence is forever. They replaced Ukrainian TV and radio with Russian propaganda channels that showed their own fantasy view of the war. They would even blast Soviet-era music on the streets and stage celebrations to film for their own TV.

For Tereshchenko and his wife, the deciding factor became their infant daughter. They didn’t want to leave, but the environment in Kherson was too dangerous for the baby. On the evening they made the decision to flee, they couldn’t stop sobbing. “We were about to rob our mothers and fathers of the happiness of being grandmothers and grandfathers.” They grieved depriving their daughter of the love of her grandparents. Olberburg and Kosiei left at the end of May. “I had a strong desire to meet victory at home,” writes Olberburg, “but with every month the situation in the city became more tense. People started disappearing. My friends ended up in the basements and were tortured.” Kosiei’s friend was beaten up at a checkpoint for his tattoos. The city became dirty and filled with Russian flags, billboards and military equipment. The atmosphere was too depressing.

Constantine Tereshchenko’s drawing of mother and baby floating in a sea of hostile forces, the Ukrainian trident hovering above.

Andrii fled Nova Kakhovka after five months of occupation. With the arrival of the long-awaited longer range artillery systems HIMARS, the Ukrainian army started hitting Russian military targets deep behind the front line. The situation in Nova Kakhovka became particularly tense after Ukrainians hit a big munitions storage facility in the city. The explosion was terrifyingly spectacular with ammunition exploding like fireworks through the billowing flames. Starless, Andrii’s musical collaborator, had his windows blown out by the force of that blast. Heavy curtains saved him and his partner from the shards. Ukrainians living in occupation have understood the necessity of these strikes and welcomed them, but the situation became more dangerous. “A lot of people left at this point. The city emptied out.” After much hesitation, Andrii finally agreed to leave when his friend suggested they travel together.

In the first couple of months of the invasion, it was still possible to flee to Ukrainian controlled territory, but towards late April, the Russians started blocking those pathways. My relatives fled towards Odesa on one of the last days it was possible to do so. After that, the only way out was through Russia. It’s unclear why Russians work that way; perhaps they want to maintain the farce that they are offering humanitarian aid to people they are supposedly liberating from Ukrainian aggression. Sometimes they also hold the local residents hostage because they know Ukrainians will not shell their own people.

Andrii and his friend traveled through Crimea, across the now partly blown up Kerch bridge and then north to Estonia. I was anxious about them because younger guys tend to be treated with more suspicion at the checkpoints. I worried they’d get sent to a filtration camp where Russia “processes” those they deem suspicious. “Troubles pursued us at every step of the way and it felt like everything that could go wrong did. There wasn’t a single day when something didn’t happen, starting with incorrectly filled out immigration papers at the Crimean border.” Their car broke down in some backwater town, which required more interaction with locals who had their own ideas about the war. The car had to be towed to the Estonian border. The journey took over a week.

Now Andrii is renting an apartment in a sleepy suburb in Tallinn, learning Estonian and trying to find work. “I am not drawn to music at the moment. I feel quite lost, even though I’m safer than back home.” He listens to very little music too. “I think I have not accepted the thought that I should start doing something. Perhaps because of the long period of inactivity in occupation, I remain in a state of waiting.” His traveling companion works long hours at a construction site. He didn’t even have the energy to answer my questions. I doubt he’s making much music.

The artists from Kherson also went through Crimea, but headed southeast towards Georgia. “I remember how nasty it was to travel through Russia. I saw a lot of cars with big Zs on the windows and trunks,” writes Tarish. “I was afraid that they would recognize a Ukrainian in me. On the way, we stopped at a roadside cafe and on their TV they showed total lies about how they were ‘rescuing’ us.” For Kosiei it was “unbearable to see the endless columns of equipment moving towards Ukraine.” Whenever he and Olberburg were stopped by police, the officers demanded bribes when they discovered the travelers were Ukrainian. At the Georgian border, Kosiei was held for five hours by Russian FSB agents after they discovered a photo from a pro-Ukrainian blog in some shadowy folder on his phone. “They interrogated me, yelled, threatened, pressured me psychologically.” Olberburg remembers how difficult it was to look young men in the eyes after they emerged from these interrogations. I imagine that waiting for her boyfriend was its own kind of torture.

Tereshchenko had an easier time at the checkpoints thanks to his infant. Men traveling with young children are generally treated with less suspicion. He managed to transport twelve of his paintings and two drawings by taking them off their frames and rolling them into plastic plumbing pipes, which he tied to his backpack. He was questioned about them at one checkpoint, but was allowed to keep them after explaining that they were icons he painted himself. I suppose religious art is acceptable to the Russians since they are now claiming to be “de-satanizing” Ukraine in addition to “denazifying” it.

Constantine Tereshchenko’s icons, which he carried out of occupied Kherson in a plumbing pipe.

After spending a few weeks in Georgia, where they were warmly welcomed, the artists from Kherson ended up at SWAN, an artist residency in Sweden, pulling each other to this safe haven one by one. There’s a whole group of them there trying to process and communicate their experience of the war. “The occupation really affected my mental state,” admits Olberburg. “There are days when I can’t keep myself together. On days like that I allow myself to be miserable, to cry a little, but not for too long because I have work to do. Everyone has their own front.” She’s now drawing fantastical, alien landscapes full of symbols, in black, gray and red. Fire still features prominently.

A painting by Olson Olberburg.

Tarish is also back to drawing and painting on paper and canvas. When asked if the experience of the war has changed her relationship to art, she says that she’s “convinced yet again of the strength and influence that art has. It is the kind of language that is understood around the world, a language that needs no translation.” Kosiei is working on a new electronic music project, which he’s not yet ready to share.

The artists are also dreaming of home. Though Russian troops have recently retreated from the city, it will not be possible to return for some time. The occupiers destroyed a lot of infrastructure as they fled. As I write this, there is no electricity, water, internet or mobile connection through most of the city. A humanitarian disaster looms as temperatures drop. They also looted everything they could carry, including medical equipment from the hospitals, computers from administrative buildings and businesses, grain and farming equipment, and even animals from the zoo. It puzzles me why anyone would want to steal raccoons and squirrels, though I’m no longer surprised at such antics. They robbed and trashed many private homes and apartments, sometimes shitting on the floor where they lived. They also mined everything. It will be a while before the city is safe enough, let alone comfortable. Nova Kakhovka, on the other side of the Dnipro River, is still occupied, though Russian presence is decreasing. I hope they won’t be able to hold it much longer.

Though the atmosphere in Kherson is jubilant, there are fears that the Russians will start shelling the city, like they did Kharkiv, Mariupol and Mykolaiv. Still, I am convinced that before long, we will all meet in our native Kherson, eat watermelons, and after attending a lecture on local history “with cocktails in hand,” we will rage at a dance party at Linza, the cultural space Kosiei and his colleagues opened just months before the city was invaded. I hope the place hasn’t been trashed like everything Russian hands seem to touch, but if it has, we will rebuild. Dress code: glam/freak/fabulous/yellow/blue/free.

“The Reed Warrior” by Marianna Tarish, showing a soldier riding a zebra from the Askania-Nova nature reserve (Kherson region), carrying a watermelon shield and wielding a reed spear in the marshes surrounding Kherson.