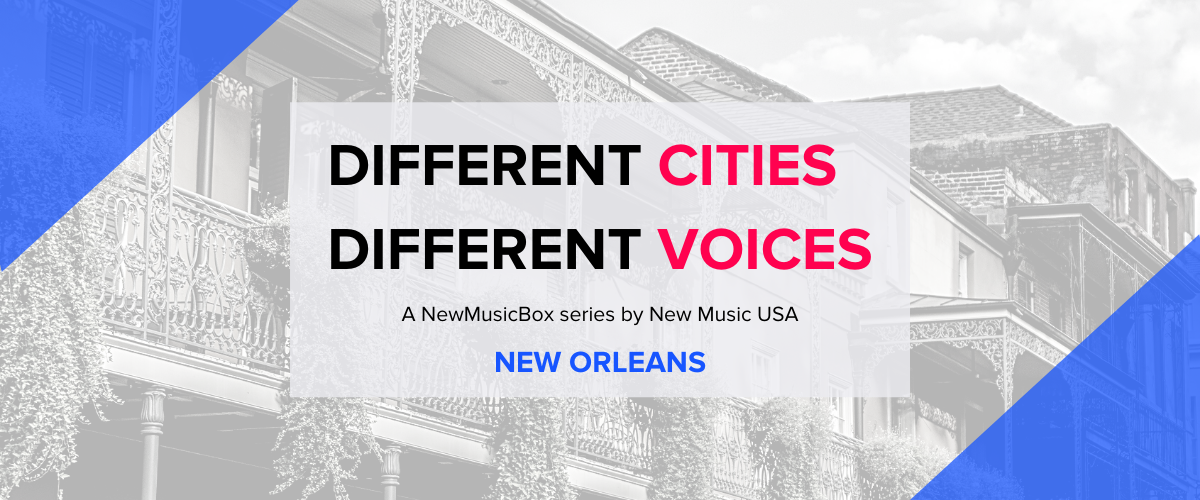

Different Cities Different Voices is a new series from NewMusicBox that explores music communities across the US through the voices of local creators and innovators. Discover what is unique about each city’s new music scene through a set of personal essays written by people living and creating there, and hear music from local artists selected by each essayist.

The series is meant to spark conversation and appreciation for those working to support new music in the US, so please continue the conversation online about who else should be spotlighted in each city and tag @NewMusicBox.

An introduction by Ashley Shabankareh

(Member of the New Music USA Program Council)

Ashley Shabankareh

New Orleans possesses a rich cultural landscape of musical talent, with tradition and community at its core. While New Orleans is most commonly viewed as the birthplace of Jazz, it should be recognized and uplifted as the birthplace of American music. Whether it’s jazz, gospel, rhythm and blues, classical, bounce, hip-hop, or brass band music, the sounds of New Orleans play a big part in our culture. Our community is close-knit, laidback, and relies deeply upon family traditions that are passed down from the older generation to the younger generation and from them to their successors.

Since the start of the pandemic in March 2020, we have seen many ebbs and flows within the New Orleans community. The pandemic hit at the worst possible time of year for New Orleans – festival season – where a large portion of income is earned for those in the music and cultural economy. Like numerous communities across the world, the pandemic caused gig cancellations, which negatively impacted many whose lifestyle often is sustained from gig to gig. Numerous music, arts, and service organizations, including, but not limited to the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, MaCCNO, and Culture Aid NOLA, quickly stepped in, offering grants, food relief, and other assistance to help sustain our musicians and culture bearers and work to ensure that our culture was not lost as a result of the pandemic. As the weeks turned to months, the uncertainty continued; would New Orleans’ music and culture be able to be sustained after the pandemic?

We began to see optimism within the community when live music was able to occur within outdoor spaces, including at porches and new opened outdoor venues like the Broadside and Zony Mash. As vaccine distribution began to pick up, performances began to happen indoors. We saw more and more gigs happening and the Shuttered Venues Operators Grant allowing more and more spaces to finally reopen. But then hope quickly turned to disappointment as what was anticipated to be a very robust festival season in the fall was canceled. Shortly thereafter, New Orleans was hit by Hurricane Ida, leaving the city without power for close to a month. Many were forced to leave their homes, and for some, they had to find a new home to live in due to damages caused by the storm.

However, despite the consistent hardships over the past 21 months, New Orleans saw our community grow even stronger than before. We’ve recently seen our City Council take steps towards the legalization of outdoor music in New Orleans, a huge step to ensure that outdoor spaces that opened as a result of the pandemic can legally continue to operate. New Orleans has also seen the Office of Economic Development propose an Office of Nighttime Economy, which myself and numerous other advocates hope will support cultural activity, not enforcement, to provide true equity of opportunity within the community.

As our vulnerable city continues to recover after both a hurricane and a pandemic, one thing is for sure – our community has become more vibrant and creative. In this installment in Different Cities, Different Voices, you’ll hear from 5 New Orleans musicians: Jason Marsalis, Helen Gillet, Clint Maedgen, Delaney Martin, and Dylan Trần.

[Ed. note: Listen to music by the contributors and other New Orleans-area artists throughout the essays below, and on our Different Cities Different Voices playlist.

Photo: Naveen Venkatesan, Unsplash

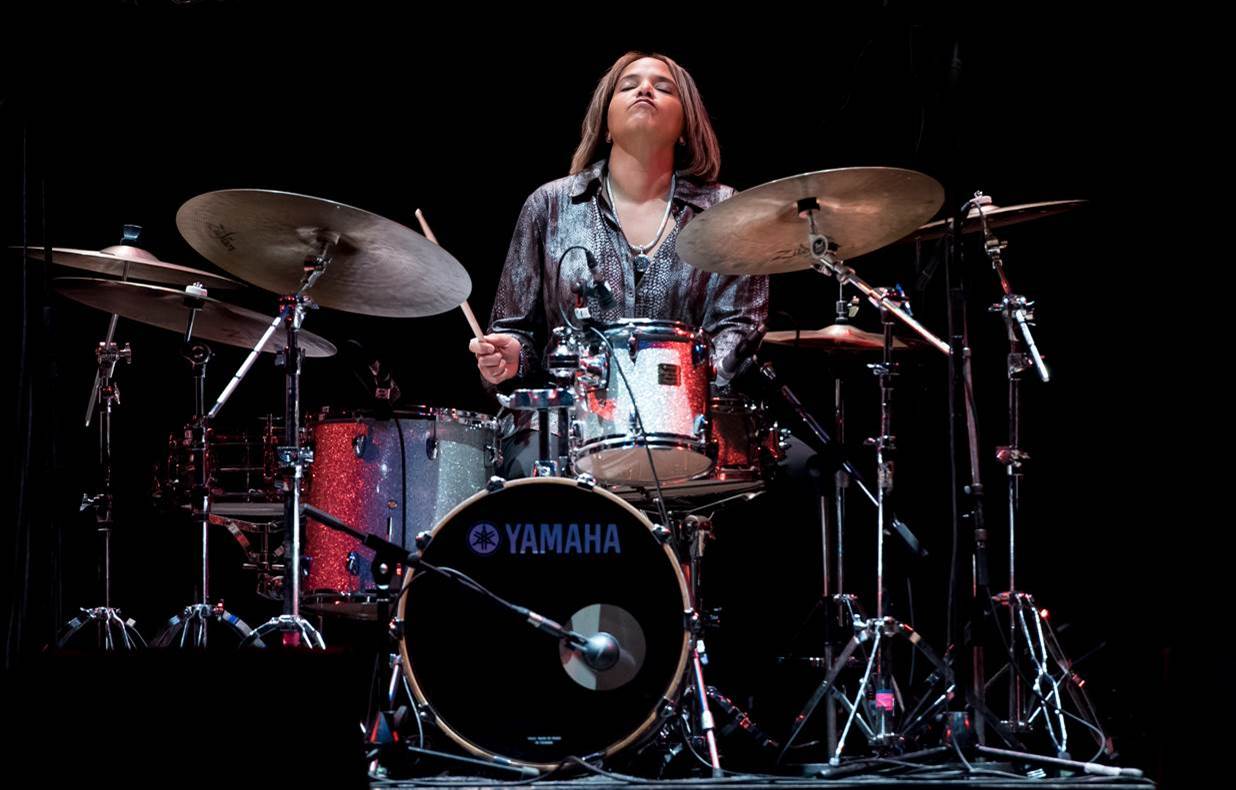

JASON MARSALIS – percussionist, bandleader

Jason Marsalis

Since I was a kid, I’ve been involved in the New Orleans music scene. Growing into adulthood, I started to see the city receive recognition that it hadn’t in previous years. A huge growth of young musicians occurred in New Orleans during the 1990s. At the same time, New York was always the place to be when it came to music. However, the dynamics of the scene changed when aspects of the music business were no longer vibrant. New Orleans has always had a connection with its traditions. Even when music changes, aspects of New Orleans groove was always in the music. However, the music in New York was deemphasizing the swing element while embracing a darker ambient sound. New Orleans was maintaining its fun element while New York was losing theirs. It was during that time I decided to stay in New Orleans.

I discovered that working in New Orleans would help me develop my “swing”; it’s an element of a groove in the music that makes the people want to dance. There are gigs that are based on the swing element that you can play in New Orleans. In New York, those gigs are not as common as they once were and many drummers haven’t developed the swing element at all because of it. Now that doesn’t mean New Orleans doesn’t have its challenges. In the past year of the pandemic, I lost my father pianist Ellis Marsalis to Covid-19. It was not only a loss for me but for the music scene as a whole. He was a teacher and leader that believed in young people playing music. He would use his bandstand as a way for younger players to grow and develop. His passing left a hole in the music scene that will have to be filled in other ways. Those ways include other people understanding how to pass on music to the next generation. As for me, even when the gigs were shut down for a year, I was able to use my creative outlet in other ways. I did more teaching, posting videos, and performing the music online. One way that I have fared with this major change is through teaching. The more music that is taught and passed on to the younger musicians, the music and all of its elements have a better chance of survival.

Listen to a Performance by Jason Marsalis:

The Jason Marsalis Quintet performs the music of Ellis Marsalis: “Three in One”

Listen to Jason Marsalis’s New Orleans Artist Recommendation:

Dr. Michael White: “Give It Up – Gypsy Second Line” Live at Little Gem Saloon

HELEN GILLET – singer/songwriter, cellist

Helen Gillet (photo by Jason Kruppa)

There were no other cellists I could see around town when I first moved to New Orleans in 2002. There were also very few women instrumentalists out and about. I was raised by strong women, so this struck me as odd. But the spirit of New Orleans music can be very welcoming to newcomers who are willing to show off their talents if they have enough sincerity, talent, and show respect to the city and the musical legacy that came before.

Sure enough, I managed to talk my way into a variety of musical contexts, convincing bandleaders I could fill the role of trombone, guitar, bass, violin, and eventually drums, synthesizer…all using the acoustic cello, and later on the looping pedal. I have learned to: “turn it up to 11” in funk bands, rock bands and even solo to play loud enough to cut through the noise of a drunken tourists yelling “Sake Bomb” as she stumbles into a Frenchman dive. Especially during the post-Katrina musical renaissance, I became a resident recording cellist around town, notably Piety Studios under the tutelage of Mark Bingham. I learned about recording music, playing in front of amazing microphones and into headphones; creating and weaving my cello parts to lift countless records for artists such as beatnik poet Ed Sanders, Marianne Faithful, Cassandra Wilson, Dr. John, Wardell Quezergue, Sonic Youth, Arcade Fire, Leroy Jones etc.

I was blessed by the city in 2004 during my first ever Jazz and Heritage Festival appearance as cellist in Smokey Robinson’s band, a decade before my first solo Jazz Festival appearance under my own name. I have been blessed by two Smokeys, the second of which was my neighbor of ten years, Fats Domino’s drummer and grandfather of funk Smokey Johnson. He became like a father figure to me, encouraging me every day to “Go lay it on ’em” and to “go get ’em killa'” — He also was instrumental in helping me figure out I had worth as an artist and how to demand more money for my music. “Girl, you know some S@&*..I hope they payin’ you for what you know!” We all need a great cheerleader in our lives, especially before we learn to do it for ourselves, and I was fortunate to find the best ones just four houses down the street from me. He helped me see past my gender and just do my thing in music. I not only managed to carve out a decent living for the past 19 years I have followed my own path along the way. Thank you Smokey and thank you New Orleans!

Earning the reputation to be a first call for innovative musical projects looking for a cello player has been a wonderful privilege. Within a few years of living here, I was playing in a musical jazz arena alongside Johnny Vidacovich, James Singleton, Kidd Jordan, visiting world renown Jazz improvisers such as Frank Gratkowski, Hamid Drake, Wadada Leo Smith, Tatsuya Nakatani, Cooper More, so many more… I played in a local Medieval Band. I am fond of my yearly appearance at The New Orleans Noize Fest, playing in spontaneous Punk Bands, Rock n Roll Circus Bingo Show, Mardi Gras Indian Funk Orchestra, Southern Rock bands, with Singer Songwriters, Traditional and Progressive Jazz, Vaudevillian French bands and even a Disco band called “Bubble Bath” — I have workshopped my Belgian inspired surrealist ideas with some of the world’s finest improvisers and come up with a style that is my own. It was a natural evolution to put all my favorite grooves, melodies, and sentiments from this plethora of inspiration into my own music.

You often feel like there are just as many musicians in New Orleans as there are houses in New Orleans. Live music is everywhere, in the streets, in the clubs, restaurants, churches, sports fields, public parks, private courtyards, schools, barber shops, coffee shops, hotel lobbies, spilling out into Steamboats over the Mississippi and up over the West Bank into Algiers Point. Since the pandemic began, that spirit made its way onto people’s front porches, rod iron balconies, driveways, car ports … you name it; if you were strolling outside on any given day, you’d likely run into a live band playing a show. When music is such an important part of the fabric of a city, the musicians are put to work. I remember drummer Claude Coleman from Ween coming up to me in the artist tent at Voodoo fest in New Orleans and saying, “You New Orleans musicians are the best in the world because you play so often with so many different kinds of bands!” People often say I am very diverse, and I would say, look at any New Orleans full time instrumentalist…they are usually playing in at least 10 different style bands often and well. I am not sure where else in the world a cellist could have gotten a more diverse musical education.

I consider myself a Stoic optimist, having had to pivot many times during hard times. I understand things are likely to be tough and living is finding ways of surviving creatively. The city of New Orleans is a good place for someone like that. The outdoor music scene has exploded in New Orleans since March 2020. I was fortunate enough to have established my solo musical presence before the Pandemic hit, allowing me to live stream with my show and reach listeners eager for entertainment. Never receiving unemployment because I was working enough remotely to not be qualified, I just pushed as hard as I could to eke out a living. I played a lot of outdoor venues and during the welcomed pockets of time between waves of variants, I have even managed decent tour schedules across the USA. During long periods of staying home, I have worked on my relationship with my city, and have built a front porch worthy of live music performances and for the first time in the 14 years I have lived in my house, some of my neighbors have been able to hear my music for the first time. I am proud to be approaching my 20th anniversary living in this amazing and resilient city.

Listen to Music featuring Helen Gillet

Helen Gillet Trio: “Tourdion” from the album Running of the Bells

Tim Green: Conn-o-sax

Helen Gillet: vielle (medieval fiddle) and cello

Doug Garrison: drums with mallets

Helen Gillet: Helkiase (Solo Album)

Helen Gillet: cello, loops, vocals

Listen to Helen Gillet’s New Orleans Artist Recommendation:

Lilli Lewis Project: “We Belong”

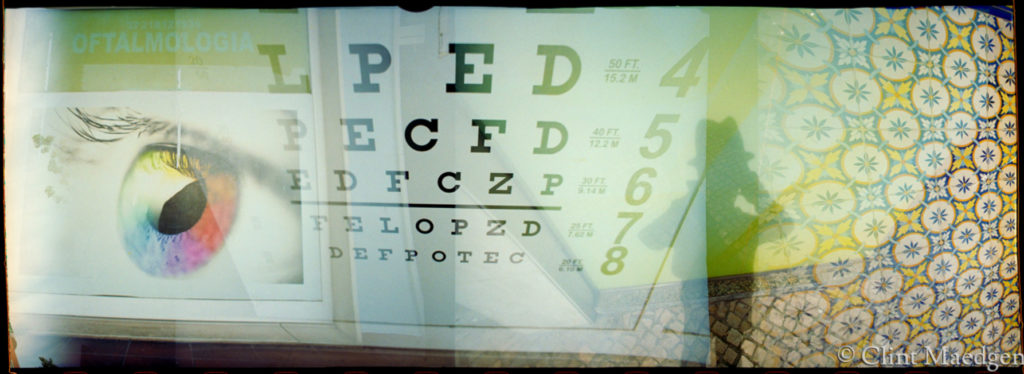

CLINT MAEDGEN – multi-instrumentalist, singer-songwriter, photographer

Clint Maedgen

I first moved to New Orleans in 1988. I wrote 150 songs while delivering food on a bicycle in the French Quarter from 1998 to 2005. New Orleans is an amazing place to be an artist, and this city has given me a lot. I have led my own bands over the years (liquidrone and bingo!) and also had the honor of playing saxophone and singing with the historic Preservation Hall Jazz Band for the last 17 years, and I’ve also taken thousands of photographs in the French Quarter and beyond.

New Orleans makes it very easy to be creative; it’s the kind of place where anything seems possible. This is also a town that still talks to one another, and that is a hard thing to live without if you’ve ever lived here and had to leave. The city gets in your bones in a forever kind of way, and I just couldn’t help but live here. I also still feel like a visitor here, and I am honored to be a small part of such an incredibly important place. Where would the world be without New Orleans? So many things started here, it is absolutely mindblowing.

As for the new music scene here today, I feel incredibly spoiled getting to hear so much music in the air at all times of the day and night. All kinds of music. Music is everywhere here. So many places to play, so many musicians. One of my favorite sonic experiences in New Orleans these days is to hear TRUMPET MAFIA playing on Frenchmen Street. The sound of 8 to 12 trumpets playing together has become this new electric current that is sent into the air on the regular, on Tuesday nights here lately. TRUMPET MAFIA is definitely a worldwide organization, but it’s amazing getting to hear them this much in New Orleans. Please check out these amazing musicians, and many more coming out of New Orleans today. It’s an exciting time for New Orleans music.

TRUMPET MAFIA concert:

Members of the TRUMPET MAFIA include: Branden Lewis, Ashlin Parker, and John Michael Bradford

This last year has honestly been one of the greatest years of my artistic life. I have performed well over 200 shows for my online subscribers, and through the use of Zoom have stumbled onto my new favorite interface for live performance. To me it’s like Hollywood Squares meets Austin City Limits. It is virtually the same audience every time we get together, so we have developed strong relationships in the context of these mini concerts that feel very intimate. Each person has their own square, so puppet dance parties are always a good idea. We have gotten to know each other over time, even though a few of us live in different countries.

Here is a three-minute sizzle reel of the PANDA FAM.

I wrote 24 personalized songs for my subscribers last year. I launched a deal where any member that purchased one of my French quarter doorbell throw pillows, I would write them a personalized song. Each person got to submit 10 words. That project set me free in so many ways, and I found the songs came to me quite quickly. The process reminded me of how I wrote music in the early 90s, recording onto cassette and ping-ponging between different devices to achieve a multi-track. It felt playful and wide open, And I love what it brought out in me.

Here is the video playlist:

As a group, we have collectively been raising funds to record each of the songs in the studio, with the intention of releasing the songs on vinyl upon completion. These songs have such an amazing energy to them, and as a songwriter I find myself amazed with an entirely new process to share and experience with an audience that really wants to be there.

Here is ELI AND THE SUGAR STATIC

As a photographer, my subscription-based audience has been a true blessing. Our group has also become a collectors club, and I have sold eight of my photographs this past year.

Clint Maedgen: Hindsight & Shadows

Clint Maedgen: Shadows & Colourburst

CONNECTION is the real currency. People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And for creators to have the opportunity to convey that message with an audience that wants to participate online, I can’t help but think that we are living in the modern day gold rush. We finally have the opportunity to cut out the middleman and the gate keepers and connect directly in a very organic and convenient way. If you love what you do and you love to talk about it and you like sharing your excitement for it, I think that this platform is perfect for all creators of all walks of life. If 500 people give you $200 a year that is a really good living for an artist. I like to imagine a world where artists perform because they want to, not because they have to. I think the answer is finally here.

DELANEY MARTIN – multi-media installation artist and Creative Director, New Orleans Airlift

Delaney Martin

I met New Orleans pre-Katrina, 1998, in my early twenties. Meeting her upended my life in the best way. I’d been a savvy kid living in New York and LA, reading culture magazines from Europe. Not only was none of that available for purchase in New Orleans, none of it mattered. Moreover, the culture here was not for sale. What New Orleans lacked in terms of a global art trending was more than made up by its incredible living culture that paraded–no–danced, down streets every Sunday for second line parades, rounded a corner in the flowing feathers and hallucinatory splendor of Black Masking Indians during sacred times each year, and kept late hours and a big beats in small neighborhood clubs that rivaled any famous nightclub I’d ever visited. And that was just the Black culture. Though less famous, the weirdo White kids were running anarchist circuses, inventing instruments, costuming on a Monday morning and just generally building such a specific-to-time-and-place culture that I realized that literally everything I had valued before needed to be reconsidered in the most joyous way possible.

I eventually left to go to grad school in London, but I deferred for a year. And I returned as often as I could in the intervening years. I built an art practice in London, but New Orleans continued to ground me at a distance. When Katrina hit, I was looking for a way to help. Starting in 2007 my co-founder of New Orleans Airlift and I began a sort of import export culture business, bringing folks like Big Freedia to NY for the first time or an artist like Swoon to New Orleans to work with us collaboratively alongside local creators we valued. I expanded my art practice to function as a framework for collaboration, building bigger ideas than I ever could on my own by having so many hands working towards a common goal. These days we are most known for our collaborative juggernaut Music Box Village – a collection of interactive musical houses hand built by artists in the dozens, an ever-expanding krewe exploring this idea of a performative musical architecture. This idea born of New Orleans is an ode to our city’s culture, its architecture; it’s the music you can hear coming through thin old walls or around the corner of your block, yet it is an idea that resonates around the world. We invite world-renowned musicians to compose and perform the musical houses. Part whimsy, part serious new music pursuit, the Music Box Village has become a landmark in our city, building off the rooted, but living, evolving culture that defines New Orleans.

I love creating here. I’ve created in many cities, but this is my speed. Jump in a truck with your friends, hit the wood dump, build from nothing, make make make, but all at a livable pace that prioritizes catharsis, ritual and release.

COVID allowed me to slow down. Slowing down and reflecting and moving with change is good. The pandemic of course shut down our performance schedule and was terrible for musicians. But it was growth for myself and for my organization. We pushed up against the obvious challenges by saying, well what do we have time for now. We were able to gather musicians we work with for conversation, have difficult conversations, make decisions to work on difficult projects around race and hard histories that continue to shape our lives. The pandemic created such a rare opportunity to make space for change.

That said, second lines are back. And we terribly missed dancing through the streets. It gives us life. New Orleans without its culture is a city with pretty buildings, but terrible education, pollution, crime, corruption!!! None of us would live here, but the culture trumps all of that and so we do.

Hurricane Ida – now that is a different story. We can celebrate the spirit of mutual aid that defined our community’s response to this tragedy, but it was a tragedy and more will come. New Orleans’ place on the map of the mind is huge, but Ida was a stark reminder that its place on the map may not exist into the very near future. Our neighbors in the river parishes continue to be without homes. This easily could have been New Orleans fate. We were just lucky by 20 or so miles. No amount of culture or music can save us. But we must save the culture. To be honest, we are still in this moment of Ida recovery – it’s too soon to say we’ve overcome it.

Because New Orleans is so storied musically, this idea that it is all tradition can become a perception problem from the outside, but it’s not really a problem from the inside. We know tradition here does not mean something stale or a museum culture. It’s all very alive down here, evolving, well-loved. These so-called traditional forms are understood to be more than music, but sound connected to the spirit in deep ways. There is not a snobbism about, say brass band culture, amongst new music people. It is a blessing that we get to be in this swirl. In turn, these so-called culture bearers are not closed off; they are welcoming. They are also experimental. The musicians we have in our space are not all people making new music. They are brass bands, they are Black Indians, they are superstars of the new music world, they are pop stars. What we give them is a context to work together in an unlikely setting and unlikely pairings. There is an openness. Recently we had two big players in their respective new music circles live in our town for some years: Yotam Haber, the Rome Prize-winning composer and Mikel Patrick Avery, known more as a Chicago character and perhaps most known for his work band leading for Theaster Gates’ Black Monks of Mississippi. We worked extensively with both of them, and the effect of New Orleans on their practice was profound – they wanted to dig in, not dig out. They’ve moved on to other cities and opportunities, but it was great to have their gifts here for a while and we knew that our city was a gift to them too.

Listen, clearly New Orleans is not a mecca of “new music”, but it is open, collaborative, and knows deep in its bones that we make music that matters to the world and so much of that music was the new music of its time.

Listen to Delaney Martin’s New Orleans Artist Recommendations:

Taylor Lee Shepherd: “The Blue Sea Hushed Him”, from Flight of Icarus @ the Music Box Village

So much to choose from at Music Box, but selecting this piece by my music box co-founding sound artist Taylor Lee Shepherd. He leads this project with me. We’ve built musical houses in collaboration and our Shake House is well heard on this track. But he is also the daily technical director of Music Box Village, maintaining all the musical houses by our collaborating artists, and so intimate with all the sounds. This song is from his one man show Flight of Icarus. For the show he exclusively used the sounds and interfaces of the houses, looping and building on their sounds via connected looper pedals he installed throughout the space.

Leyla McCalla: “Mèsi Bondye” from Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes

I really like this particular track. Sort of a nice spare, feminine counterpart to Taylor’s Shepherd’s piece. It also speaks to the evolving exploration of rooted music that New Orleans artists explore – in this case both Leyla’s and New Orleans’ deep connection to the music and culture of Haiti.

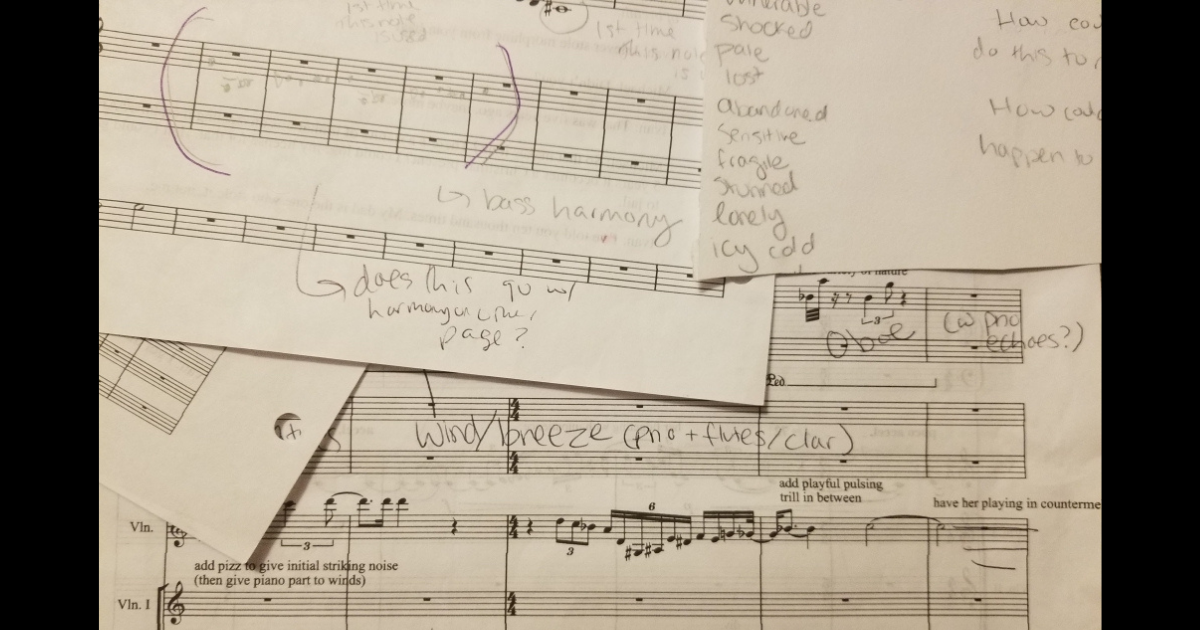

DYLAN TRẦN – composer and Marketing Coordinator at New Orleans Opera

Dylan Trần

My experience in New Orleans can be summed up in one word: opportunity. I’m a first generation American on my dad’s side, born into poverty in the Deep South. If it weren’t for the fact that Loyola University New Orleans has a free undergraduate application and ample scholarship opportunities, I’m not sure I would have been able to go to college, much less pursue a career as a composer. Even my career as a composer, at this point, is only financially possible because of my administrative position at the New Orleans Opera Association.

Throughout my undergrad I had many interests: conducting, composing, singing, film, photography, marketing, languages, history, diasporas, media, activism, sociology, etc. I had very supportive professors in all of these areas that encouraged me to develop my skills in these interests; this held true when I left school as well. This is a huge reason I have stayed in New Orleans— as my artistic career evolves, the city has allowed me to discover, create, and share opportunities to facilitate my growth and exploration.

The reasons I believe this city is so prime for making your own opportunities is a bit of a double-edged sword. There’s a famous Cajun French phrase, “laissez les bon temps rouler” (let the good times roll). That lovely, laidback vibe permeates the music scene as well, setting the scene for the biggest challenge I’ve experienced in New Orleans—outside of jazz, funk, and other popular genres, there is a lack of infrastructure for “classical” music artists. Because of this, most of my commissions come from online and social media networking, as opposed to local groups.

In a way, this lack of infrastructure creates space, an opportunity to build community and art without having to follow an extant institution’s rules—but, the work is not easy. As artists, we are no strangers to being our own advertisers, agents, accountants, etc., something I experienced intimately while I was pursuing a local singing career. As a composer, however, one of the only ways I’ve been able to create the art I want is to take on the additional titles of project manager, development officer, employee organizer, community liaison, etc.—basically running my own small business.

This may sound scary to someone who is trying to be exclusively a composer, but if you are someone in a more exploratory part of your career, New Orleans is an excellent place to do that. I don’t think there are many other places where I would have had as many opportunities to be compensated for trying new things. I’m not just talking music commissions either. I’ve been hired to direct music videos, film documentaries, write articles, run marketing campaigns, develop guest instructor lessons, be a guest speaker, etc. I did not have a huge amount of professional experience with many of these things prior, but because of the nature of the city, if you put some work in and cash in some social currency here and there, you can really explore anything!

Beyond that, I do think the “classical” new music scene in New Orleans is in a blossoming era at the moment. In terms of large organizations: the Marigny Ballet regularly performs world premieres, the New Orleans Opera Association (while not a regular commissioner of new works) is known for championing second and third performances of emerging works, and the LPO will occasionally commission a local composer to accompany an extant “canonic” masterwork. Versipel New Music is a particularly talented collective working exclusively in new music, and there is New Music On The Bayou in North Louisiana, but I am not familiar with many others locally. That being said, every year, I meet more and more composers and groups in the city, so I believe that, while the new music scene may be small at the moment, it is vibrant, growing, and will continue to flourish.

Stepping outside of strictly “classical” new music, the New Orleans musical world opens up tremendously. Some days it seems like there isn’t a genre unrepresented in the city. Hip-hop, folk, indie, jazz, rock, metal, and indigenous musics are ubiquitous in the community. More and more as of late the larger “classical music” organizations have begun to reach out and collaborate with these other genres. For example, it has happened on more than one occasion that the LPO will share the stage with Tank and the Bangas. If you are interested in exploring many genres of music, and the intersections and collaborations therein, New Orleans may be the place for you.

Listen to Music by Dylan Trần:

Dylan Trần: String Quartet No. 1 on Việt Themes

Listen to Dylan Trần’s New Orleans Artist Recommendation:

Lilli Lewis: “Incantation: Wind”

Listen to the Different Cities Different Voices playlist on Spotify:

The series is meant to spark conversation and appreciation for those working to support new music in the US. Please continue the conversation online about who else should be spotlighted in each city and tag @NewMusicBox.

Photo: Mana5280, Unsplash