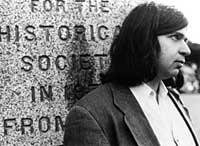

Gary Lucas

Photo by André Grossman, courtesy Gary Lucas |

NewMusicBox Editor Frank J. Oteri visits composer/guitarist Gary Lucas at his home.

Thursday, June 22, 2000, New York City

Transcribed by Lisa Kang

Poly-Stylism and Influences

FRANK J. OTERI: This is a great place. I love being surrounded by tons of vinyl, and I see you are quite a record collector.

GARY LUCAS: I think I spent a lot of my formative years collecting music. I was obsessed about it, but it really has tapered off in the last couple of years, I must say. I’m not nearly as driven to do it and I think it has something do with making music for a living and going full time professional. I felt a little guilty in the time I would spend listening to new sound. I was eating up time that I would have otherwise conserved putting into use making my own music.

FRANK J. OTERI: This is the incredible divide that I find myself in constantly. I mean, do you make music or do you listen to other people making music… I’m addicted to both!

GARY LUCAS: I know, if you can find a balance it’s good. I try to keep a balance, and I do manage to keep abreast of everything. I was listening to Tony Conrad and some of the recordings that Table of the Elements has put out recently. They just sent me a vat of stuff.

FRANK J. OTERI: Terrific. The one that I want to listen to is Outside the Dream Syndicate.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, I know. Well, they swore they would send it to me but the release had been delayed a bit.

FRANK J. OTERI: Do you know the story about Conrad showing up at a La Monte Young concert with a picket sign?

GARY LUCAS: My drummer plays in La Monte’s Forever Bad Blues Band. La Monte has been guarding his tape archive quite zealously.

FRANK J. OTERI: Anyway, to bring the conversation to you and the music that you spend time doing versus buying music as voraciously as you used to… How would you describe your music to someone who has never heard it?

GARY LUCAS: I’ve kind of developed a rubric. I’d say it’s “psychedelic primitive.”

FRANK J. OTERI: What does that mean?

GARY LUCAS: It embraces the energy of the caveman, hopefully, and a kind of a visceral, teeth gritting that also pertains to the psychedelic, mind manifesting impulse that turned me onto listening to music voraciously in the ’60s, and that I like to take people on trip with the guitar. I like to make the music in a way kind of pictorial so that my instrumental music can describe landscape and ideas. Ultimately it’s visceral. Recently a fan wrote me on the Internet and said that I ought to distribute “Gary Lucas Chewing Gum” with all of my records because it gave her a very tactile sensation. It was kind of like she could chew the music. That’s how she described it. What does that mean? I don’t know.

FRANK J. OTERI: When I was listening to your CDs, I felt like I was being taken in so many different directions with this music and I came up with all sorts of things I was hearing – I was hearing rock in it, I was hearing jazz, and I was hearing blues, and I was hearing roots country at times, I was hearing new music, experimental music, electronic music, Klezmer and the Radical Jewish Culture thing. It was all there. There were even tracks that were like heavy metal and hip-hop .

.

GARY LUCAS: I cover the waterfront. What can I say? (laugh) I think I can find some beauty in every genre of music that I’ve listened to, and I think that I don’t discriminate, I don’t narrow-cast my music to aim at one particular market. This could limit me commercially of course because I think the way music is packaged these days, people want an easy kind of free ride so that they don’t have to work to understand what it is that they’re listening to. Everything is boiled down into these generic constituents, so that you go to one source for your hip-hop, go to your alternative rock section in the store, you know, to get this and that.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s amazing to me that alternative rock has become codified because the whole notion of alternative rock is that it goes against the codification that rock became.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, it’s true. This is just the function of the marketing mechanisms of the world in that the people in corporations who are behind the masked music foisted on everybody definitely go toward the generic or the lowest common denominator because it’s easier to sell, they don’t have to spend a lot of time describing what it is to people. If people have to think a little bit, if they have to work to apprehend what it is they’re hearing, they find that most people don’t have the time in their lives to devote to such things. Anyway, music is used by most people as an adjunct to other activities. I really wonder how many people actually sit and listen to something rather than using it as background music while they have breakfast or brush their teeth, watch TV, or some other activity. Just to have something on, a soundtrack or background music to their lives.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, the whole reason why I wanted to have this discussion with you is that the July issue of NewMusicBox is all about how non-commercial rock music, truly alternative rock music, is very much a cousin to contemporary, so-called serious music, art music, music that really has no name that works for it… These two worlds are very close together and I think we could learn a lot from each other, and I think there would be greater strength in what we do, and certainly when a band like Sonic Youth last year turns out an album with Pauline Oliveros and Christi

an Wolff and all of these people, it shows you that these worlds aren’t really that far apart.

GARY LUCAS: I think that the impulse to experiment which is at the heart of new music, the impulse to make it new, as Ezra Pound said, there’s an ethos that’s shared by rockers because their music is a reaction to whatever had been the prevailing rock music trend of the time. Both groups seem to share an impulse to want to deviate from the norm, which to me is good and is what attracts me. I’m very rebellious at heart. I have a problem with authority figures.

Beginnings

FRANK J. OTERI: Now you’ve been playing music pretty much since the 1960s…

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, the first time I picked up a guitar was at the age of 9 which was 1961 – well that blows it – I just had a birthday, you can work it out.

FRANK J. OTERI: (laughs)

GARY LUCAS: My father came to me and said, “How’d you like to play the guitar, Gary.” I never had any notion of playing anything so he put the bug in my ear, and I thought, ok that sounds like a good idea, so he arranged for me to take guitar lessons which lasted all of about three to four weeks. I was hopeless. They had rented me a practice guitar, which the strings were about 11/2 inches off the fret board, so physically it was very painful to try to grapple this thing. At the same time I had taken an aptitude test at elementary school, a music aptitude test, and I had scored a perfect score 100 on this test, so the band leader in this school decided that I was therefore a natural candidate for the French horn which was absurd because as you can see I barely have an upper lip, so I couldn’t really develop a great embouchure on this instrument. It is very difficult with the intonation being what it is to play the French horn. Nevertheless within a week of taking guitar lessons I also started taking French horn lessons to play in the school band. So that immersed me in music. Prior to that I spent years sitting in a rocking chair in the basement of my father’s house listening to Top 40 radio and bit of the FM radio of the times, so I soaked up a tremendous amount of music that way.

FRANK J. OTERI: What was the first stuff that excited you musically.

GARY LUCAS: Oh, Duane Eddy, Dance with the Guitar Man. That was the first album I remember purchasing. I definitely aspired to learn to play that on the guitar, as well as the theme from Peter Gunn. That really turned me on. And I loved Tchaikovsky‘s 1812 Overture, the sound track to Peter Pan with Mary Martin, my parents had lots of Broadway show tunes playing in the house in the ’50’s when I was growing up. As well as a lot of light, easy listening albums of the day.

FRANK J. OTERI: Although in the ’50’s a lot of that easy listening stuff was really not so “easy”…

GARY LUCAS: Now it’s contemporary…

FRANK J. OTERI: Les Baxter and Esquivel did some pretty out there stuff…

GARY LUCAS: I liked that stuff. I’d go to my neighbor’s. I had these friends who lived in Syracuse, and they had quite a bit of what’s now called “lounge music.” I thought it was terrific.

Leonard Bernstein

FRANK J. OTERI: Now, in the early ’70s, you somehow got connected to Leonard Bernstein.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, that occurred when I was in my junior year of college. So I had been playing guitar for a while. And I saw that the Yale Symphony Orchestra was auditioning to be players of Leonard Bernstein’s Mass, which was a theater piece that was premiered at the Kennedy Center I think in ’72 or ’73. And they were preparing the European premiere in Vienna so I went to the powers that be at Yale, that was John Mauceri who was the conductor of the Yale Symphony then, and volunteered my services as an electric guitarist because there was a part calling for this, and I got the gig. And this enabled me to make my first to Europe. We went to Vienna for two weeks to work on this and it debuted in the summer of 1973. And I remember I think 800 Catholic bishops in Austria protested this work as blasphemous, a slur on the Catholic Mass…

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s quite a wild piece…

GARY LUCAS: It is a wild piece, but it definitely comes on the side of peace and religion. It’s you know, not disrespectful, per se.

FRANK J. OTERI: Did you get to work with Bernstein?

GARY LUCAS: A bit because he came to supervise the production right before the opening night, and he gave me specific tips on how he thought the part should be played, because I’d asked him one of the parts that I was required to do was to do a wild, psychedelic blues, rocked out, guitar solo, and it occurred in the moment that was supposed to signify the most decadent, orgiastic scene in the piece, this was to represent the decay of western civilization at this point which you know religion was there to help prop up and preserve. So I said, well, gee, whenever you use electric guitar in this piece it’s always the most decadent and blasphemous part of the production… He counseled me to just sink my teeth into it and rock out. I loved Leonard Bernstein.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well he’s someone who’s coming from an interesting place. I don’t think we’ve had anyone like that since. He was entrenched in the classical music establishment as a conductor. But as a composer, he was also on Broadway, he advocated Jazz on television in the ’50s, he was advocating the Beatles… He was all over the place at time when people were really divided into camps.

GARY LUCAS: There was a great show that was on CBS in ’67 called The Age of Rock. (I have a bootleg copy of it.) He hosted it and talked about how much he loved the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles, Tim Buckley… They played Tim Buckley’s music…

FRANK J. OTERI: Wow!

GARY LUCAS: Brian Wilson had just composed the song “Surf’s Up” and there was a vignette with that, and Frank Zappa, and I think he was cool. He was a big inspiration to me growing up. I used to really soak up the Young People’s Concerts. That’s how I learned a lot about Stravinsky, and Mahler, and it was just great.

FRANK J. OTERI: I think Mahler is a major world figure today because of Bernstein’s advocacy. Before that no one was regularly conducting his symphonies. They’re standard repertoire now.

GARY LUCAS: Yup. Right. God bless Lenny, I think he was a saint in music, and we really need someone of his stature today, I think, to help educate young people coming up.

Other Musical Heroes

FRANK J. OTERI: Now in those formative years, who would you say were your other musical heroes?

GARY LUCAS: Well, certainly, I loved early British invasion music.

FRANK J. OTERI: Like the Kinks?

GARY LUCAS: Oh yeah. I think I was one of the first people to ever hear The Who. My uncle was a rock promoter in Rochester and brought The Who to play on a package bill before Tommy. I love the Yardbirds. As far as guitarists go, I mentioned Duane Eddy, but Jeff Beck was my idol of the ’60’s, also Jimmy Page, and, of course, Clapton. But to me Beck was my favorite – he had a real sense of humor that he translated on the guitar which I hope I have incorporated in my playing as well. And I liked more a little bit of the more obscure players of late ’60’s like Syd Barrett who was Pink Floyd‘s visionary guitarist and main song writer in their first albums. I loved this guy named David O’List who played in the Nice. I think he was amazing. And then of course all the country blues players such as Son House, Skip James…

FRANK J. OTERI: You have an homage to Robert Johnson on one of your albums, it’s really fantastic.

to Robert Johnson on one of your albums, it’s really fantastic.

GARY LUCAS: I liked all this music, and I first heard it actually because I loved Captain Beefheart‘s music. I’d been hearing the British take on the blues without investigating the origins of it, and later, joining Beefheart’s band, it sent me back into really immersing myself in country blues and Chicago blues styles. And I heard the antecedents to the British blues players that I loved. And I have to also mention Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac. I think he’s one of the best, all around, blues players that I’d ever heard….

FRANK J. OTERI: One thing I was hearing, I don’t know what you’d think of this combination of influences, but I guess it was it was your first solo album that I was listening to very early this morning, and I was listening to this great instrumental track and I thought it had the technical proficiency, and structural clarity of Robert Fripp with the looseness and easiness of Jerry Garcia combined.

GARY LUCAS: I definitely appreciate the playing of both of those figures. After a while I stopped listening to the original players, to try to use whatever influences I already soaked up and hopefully, continue to forge in my own voice. To me Fripp is a fantastic player, but he’s always tight, he gets a little bit too anal retentive for me to listen to a lot. Jerry Garcia is a great player in his open, free wheeling style. But overall, I’m not really one of those stoned out Deadheads who followed the band. I liked a few moments of their records, and that was it. There weren’t that many groups that have been able to sustain themselves for me to play more than a couple of records.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now you mentioned Zappa at some point.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, I really loved the early Zappa up to about Hot Rats. And then when he go into the riffing jam albums to fusiony albums after that, or the really puerile social satire albums, he lost it for me.

FRANK J. OTERI: My favorite will always be We’re Only In It For The Money.

GARY LUCAS: I love that. That’s a classic album! Such a unified statement… I think he had moments that I would hear, but I didn’t really pursue him as a fan, I didn’t slavishly go out and buy the records. And then the guy put out about 80 records. I’m sure they are all high quality, but I don’t have the time or the patience to absorb so much music when I’m trying to make my own music or think about the world. I mean, God bless people who are so obsessive… for myself I think that maybe of all the groups, the Rolling Stones and the Beatles had the highest number of quality records that you could really listen and which would stand out and stand the test of time.

Captain Beefheart

FRANK J. OTERI: Let’s talk some more about Captain Beefheart [a.k.a. Don Van Vliet] because he is somebody who’s almost like an equivalent figure in rock to someone like Harry Partch, someone who was really unique and created music exclusively on his own terms.

because he is somebody who’s almost like an equivalent figure in rock to someone like Harry Partch, someone who was really unique and created music exclusively on his own terms.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, a diamond in the ruff, an Absolute sweet generous genius…

FRANK J. OTERI: And someone who is completely under-appreciated like Partch largely due to his own reluctance to play the music industry game.

GARY LUCAS: He liked to subvert the game. I mean, Zappa was able to carve a niche out of a social center of the time for himself. And took swipes at a lot of obvious targets. I mean, he said a lot of things that needed to be said, and he relied on a certain level of satire. Don’s lyrics I think were a lot more poetic and obscure. They’re like puzzles that need to be worked out. But once you get into the flow and I think they become self- evident but you have to work at it a lot harder than with Frank. Frank served up his satiric observations more or less on a platter. It wasn’t hard to figure out what he was saying. Don was a just a bit more on a higher, more rarified plane than most people in the world; he was really willing to do the work. Also, for a few of his records, he was attracted to making genuinely radical, revolutionary, new music approaches and a lot of people found them too difficult. The first time I heard Trout Mask Replica I thought it was utter chaos, I didn’t really see the plan behind it.

FRANK J. OTERI: And it was all recorded what, in an 8 hour session…

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, and it was rigorously worked out.

FRANK J. OTERI: Notated arrangements?

GARY LUCAS: Well, notated by people in the band who were able to write it out. Don really never wrote music out. But it was certainly memorized. It was through-composed and then codified. So like classical music, there was no improvisation other than his vocal and saxophone playing on the record. But saying that, to me it stands as the most brilliant, classical music of this century. I rate him as a Titan of music. I rate him as one of the greats, he’s right up there with Stravinsky as a composer. And as a writer I think his poetry is second to none. People go on about as a great rock poet, and Dylan. I think they are both gifted, but I think Beefheart was really ahead of them. His stuff really reads more like poetry for me.

FRANK J. OTERI: And he’s always had incredible sidemen. It’s interesting to look at the trajectory. The very first Beefheart record, Safe As Milk, had Ry Cooder and the very last Beefheart record had you.

GARY LUCAS: (Chuckles) I hope I’m upholding the tradition. You know I feel that it was my first goal in music to play with this guy. I mean, after seeing him in New York City at his concert debut in 1971 in a little club which no longer exists, I made a vow that if I ever did anything in music it would be to play with this guy. I came down with some buddies and drove in from New Haven. I’m a Yalie. And I heard the records, but I wasn’t prepared for this. It really took me over. I thought I’d never heard a guitar played so brilliantly and uniquely, and that’s what I wanted to do. From that point on, it was my goal to play with this guy. And I announced it to my friends. Luckily about 6 months later he came to play a show at Yale, and I was the music director at the radio station at that time, so I was assigned the task of interviewing him. And I have a tape of it somewhere – my voice was shaking. You know, he was on the cover of Rolling Stone, he had a reputation of being a heavy psychic. And he was very affable on the phone, charming and funny. And then meeting him I was convinced that there was a genuine presence.

FRANK J. OTERI: And luckily you got to him just before he gave up playing music. Any thoughts as to why that happened?

GARY LUCAS: He was very discouraged with the kind of limited nature of the record business. He had never really broken through in any commercial way. So he was still getting contracts to make records, yet they weren’t for a lot of money on the front end, and he wasn’t seeing anything on the back end. He really hated to tour; he hated the rock circus. It was taking its toll on him. You know I did the last European tour and most of the American tour in 1980. And afterwards he was just shuddering with disgust before going out on stage, I remember, in San Francisco for instance. So he just saw painting always as a much more creative expression for his personality. I disagreed with him because he made pronouncements to me and to the press that in his mind painting went a lot farther than music as an art form. Be that as it may, he made the decision do to that full time, and I’m proud that I helped usher him into making that transition to full time painter. He had been painting and sculpting since he’d been a kid. But I’m sorry he decided to stop doing music. We had a contract to do another record with Virgin after Ice Cream for Crow but he ignored it. He really didn’t want to put himself through the rigorous agonies of making a record. He’d turn himself inside and out to do these things.

FRANK J. OTERI: Is he writing at all? Do you keep in touch?

GARY LUCAS: I haven’t been in touch since the mid-80s, and I’m not sure how he’s doing. I hope he’s well. I went to an art exhibition a couple of years ago at a gallery on the Upper East Side here and was proud to see the work being displayed. And they were selling for a lot of money, so I hope he’s doing well. I don’t know if he’s continuing. But knowing him, this was a guy who never turned off. He was constantly writing poems, and dictating them into little tape recorders, and coming up with m

usic parts, and whistling, crazy parts that he would have the band run again into a tape recorder… He was always sketching; he had hundreds and hundreds of notebooks filled with beautiful drawings. So I hope he’s still keeping up with the output, although I had heard rumors about his health problems. I saw a documentary that the BBC made a couple of years ago, and he sounded pretty ill, I mean just from the tone of his voice. And I had heard he had M.S., but I don’t know for a fact. I hope he’s well.

Literary Heroes

FRANK J. OTERI: Now you talked as well about Beefheart being a great poet as well as being a great composer. Now, you also write words for your albums. Who were some of your other literary influences?

GARY LUCAS: I love James Joyce, I love Shakespeare. You know I’m a graduate in English literature, so I have a sort of traditional English Lit background.

FRANK J. OTERI: So not music.

GARY LUCAS: Well, I took some music theory classes, and left them after a couple of sessions at Yale. I didn’t think they’d enable me to do what I wanted to do. I always had a facility to write. I got into Yale probably because I’d won an international award for composition when I was in high school. I’ve attempted to write a novel. I have an art novel somewhere in a drawer that I had abandoned when I made the decision to do music full time. There was a guy named Wyndham Lewis who’s not nearly as well known as Joyce, but to me is right up there as a stylist, as a radical, thinker and writer of the 20th century. He was very naïve politically and got branded as a Nazi sympathizer and a fascist, both of which ideologies he recanted before he died. And he apologized for some statements that he’d made. But he wrote some amazing books such as The Apes of God, and his first novel Tarr is, in the early edition (…it was revised…) it’s just one of the most radical prose styles, and unique prose styles anyone came up with. And there are some affinities in some ways to some of the lyrics Beefheart later did, and I turned Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) onto Wyndham Lewis, and he became a tremendous fan of the work and used to read the books voraciously, and would have me read them to him when the Magic Band was on tour in the UK in 1980 as we drove from gig to gig in the van. Lewis is a hero of mine. I like Nabokov very much. Actually, my last literary passion in a huge way is Isaac Bashevis Singer. And I’d say he’s actually replaced all of these figures as — if I was stranded on a desert I’d ask for some of Singer’s books to take with me. I love his writing. I find it very evocative. Of my roots, my grandfather and grandmother came from Poland. They were Polish Jews. And my father’s relatives come from Bohemia (which is the Czech Republic), Hungary, and also have a little bit of German Jewish blood. So reading Singer, especially when he deals with the old world, the Jewish community right before it vanished by the onslaught of the Nazis, I find it tremendously moving emotionally.

FRANK J. OTERI: That’s actually an interesting irony about being very into Jewish heritage and at the same time being a huge fan of Wyndham Lewis…

GARY LUCAS: I know, I don’t know what it means – I’m not a self-hating Jew. I’m very proud of my heritage, and right now I’m working on a record for John Zorn‘s Tzadik label. I’ve done one already, part of the Radical Jewish Culture series  . So it’s taking up some of my pre-occupations and my roots. To tell you the truth, I think I had a small influence on John.

. So it’s taking up some of my pre-occupations and my roots. To tell you the truth, I think I had a small influence on John.

Establishing a Solo Career

GARY LUCAS: In 1988 I began my solo career under my name, seriously, at the Knitting Factory on a dare. A friend of my dared me to put a concert together. I knew Michael Dorf; he’d been up in my office at CBS Records where I labored for about 11 years as a copywriter. And I’d been to the club. I’d seen Tim Berne, the alto saxophonist/composer, perform there, and Zorn. So it seemed an attractive space for new music. And anyway, I was given this challenge to do this solo show, and I had the bug to be playing again after some years in limbo. Beefheart split up the band in ’84 to do the painting full time. And I had a few years where I wasn’t sure what my next move would be musically. I continued to play the guitar for my pleasure, but I wasn’t taking up offers to do anything — I had some offers to join bands, and what not. And I thought after playing with the number one avant-garde band, what was I to do? I had to really think about it. Then I got side tracked in producing some records for CBS Records, now Sony Music. I did a Tim Berne record first for Columbia, and a Peter Gordon record for Masterworks.

FRANK J. OTERI: Innocent…

GARY LUCAS: Yeah. Then I met a band called Wooden Tops, an English band that I liked, and they invited me to play on their record. And I flew to London, and in these sessions, this was about 1988, I reconnected with my love of playing. And I thought, “I should really be doing more of this.” So I started to do more session work for people like Matthew Sweet and Adrian Sherwood. And it started to make sense again. Anyway, then I put the show together in the June of ’88, my solo debut at the Knitting Factory in New York. And despite them leaving me out of the ad for the week, it happened. I had absolutely a sold-out house. They turned people away. And I got wild ovations from the crowd and I felt really a sense of empowerment that night. A friend of mine said it was like a seeing a little sea monster, a Loch Ness Monster, raise its head above water and look around. I just thought, this is what I should be doing. It became obvious, you know, because I was pretty miserable as a copywriter. I could do it but it was just rotting my brain.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s interesting to think about that in classical music, a composer usually studies music composition, and develops some sort of relationship with the composer he or she is studying with, and then does his or her own thing. But in the jazz world and the rock world, you’re a sideman with someone and that’s sort of the equivalent of going through that process. At what point did you decide, “Well, I’m a composer in my own right, I’m a leader in my own right”?

GARY LUCAS: Around this time. Because it seemed I had psyched myself out of attempting to write songs and to compose music, out of fear, basically, that it wouldn’t measure up and it wouldn’t be any good. It was just kind of insecurities, you know, everybody goes through them. Then I got to a certain age when I thought, I don’t care. What do I care If people didn’t like them it’s their problem. But I’m going to do this now. It’s now or never, really. Time to get really busy, or it’ll be too late. Here I have a window of opportunity.

FRANK J. OTERI: How did your involvement with the whole Radical Jewish Culture thing begin?

GARY LUCAS: Well, in November of ’88, I was invited to play my European solo debut at the Berlin Jazz Fest. It coincided with the 50th anniversary of Krystallnacht, which was the night in 1938 where Jewish shops throughout Germany were trashed. It was sort of the beginning of open season on Jews, right before the beginning of World War II. So when I got over there I saw in the newspaper that it was an anniversary, it just got me inspired. I was thinking, ok, I’m going to do a piece about my feelings concerning Krystal Nacht. And I did in the evening performance at the end called Verklärte Krystallnacht, a play on Schoenberg‘s Verklärte Nacht, one of my favorite pieces, Transfigured Night. So I came up with Transfigured Krystallnacht. And it actually drew on some of the music that later I channeled with The Golem.

FRANK J. OTERI: Which is wonderful by the way.

GARY LUCAS: Thank you. Anyway, I played it, and the audience was stunned. I said, “That was Verklärte Krystallnacht” and then there was this “ach”, but then I got an ovation. Then the next day the paper said, “Est ist Lucas”, “It is Lucas” with a picture of me. I don’t know if this piece was the one that particularly sparked this off, but they were in love with what I did.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now when you say “piece,” was this an extended composition?

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, but it was sort of an improv. A lot of my compositions have themes, but there’s plenty of space to improvise around them. The next day too, I saw Zorn who was over there with Naked City, and I had known him since the days I used to go into the Soho Music Gallery where he was a clerk before he got really famous. I used to go in there to get him to put up pictures of Captain Beefheart and the Band, we talked a bit, so we knew each other, and I like John. So I said, “John, John, I got to tell you I did this piece last night called Verklärte Krystallnacht, it’s the 50th anniversary of Crystal Night,” and his eyes got really big. I saw that this tumbling around in his head. It made an impression on him so much so that a few years later he came out with a piece called Krystallnacht, and he debuted it as his First Congress of Radical Jewish Culture. He had a festival in Munich in ’92, and invited me to do The Golem. So that, and plus, then I came back to New York and then started immediately to work on the soundtrack on the The Golem film. It’s a classic 1920 German Expressionist film which is more or less a Jewish Frankenstein story. He was aware of that; he heard about that. So I think this and the fact that Don Byron had done music by Mickey Katz, we were sort of like the early people coming out of this Downtown scene doing Jewish themed music. And it finally registered with John, and he got busy a few years later and started to devote his writing to Jewish-preoccupied themes. He came out with Krystallnacht, and he started Masada, and he started the label. And you know more power to him. He did quite a mitzvah in his life for lots of people, and it’s good for society, in general, to get this work out.

on the The Golem film. It’s a classic 1920 German Expressionist film which is more or less a Jewish Frankenstein story. He was aware of that; he heard about that. So I think this and the fact that Don Byron had done music by Mickey Katz, we were sort of like the early people coming out of this Downtown scene doing Jewish themed music. And it finally registered with John, and he got busy a few years later and started to devote his writing to Jewish-preoccupied themes. He came out with Krystallnacht, and he started Masada, and he started the label. And you know more power to him. He did quite a mitzvah in his life for lots of people, and it’s good for society, in general, to get this work out.

Leader vs. Sideman

FRANK J. OTERI: I want to talk a little more in this issue about being a sideman versus being a leader, and I want to bounce it off of your scoring a silent film, dealing with a pre-existing work, and adding to it which is sort of along the similar lines of knowing another artist’s work, and then becoming part of that artist’s work by being a sideman on an album or in a concert, which is a very different process than being a leader and taking the music in the direction you want to take it. You’ve done a bunch of TV scoring. I was looking at this list of stuff that you did – you did scoring for the documentary on 20/20 about the Unibomber. That obviously shaped the music that you were doing for these things – that’s on one side of the scale. And then on the other side, you’ve worked with everybody from Nick Cave to Patti Smith. How do you feel that your own identity as a musician got through in all of these different projects, and did that always happen?

GARY LUCAS: I think that I am a bit of a chameleon when I’m asked to play on other people’s records in that I’m able to adapt to the persona of that artist, and it kind of comes though in my playing. But hopefully there’s still that Gary Lucas element, and that’s why they would ask me to play with them anyway, so that also has to be there. It’s interesting. There’s a give and take, kind of thing, and it changes from situation to situation. When I’m asked to do the TV music, or the film scoring, I try to give as pure, unadulterated example of what I can do, and I am often told to tone it down only because of the nature of the medium. You know there’s a thing, especially with documentaries, where they don’t want you to color the news too much, which is to overemphasize the emotions that you’re supposed to feel by exaggerating these characteristics in your music. It really is different. Uh, if you ask me about specific people, I could better tell you how I approach the job. It’s intuitive.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s interesting because your assignments were all these terrorist stories, the Unibomber, Waco…

GARY LUCAS: It always seemed to me that whenever there was death in the air, somebody up at ABC News would go, “I wonder what Gary is doing.”

FRANK J. OTERI: (laughs)

GARY LUCAS: And I don’t know why that is except that I love life, I’m not death obsessed, but there is this kind of energy, grotesque-rry about some of the music that I do, so that they might think I’m a good candidate to do kind of music that is more on the wilder shores…

about some of the music that I do, so that they might think I’m a good candidate to do kind of music that is more on the wilder shores…

FRANK J. OTERI: On the same token, you wrote a song for Joan Osborne, “Spider Web” which was a big hit…

GARY LUCAS: It was a top selling tune on a top selling record. Yeah, why is that? I think that it’s basically because I embrace the unity of music, I don’t really discriminate in my taste to reject things out of hand. Like I like top music when it’s good. I think Joan, and the music that I was allowed to work on, or was encouraged to work on, I should say, had given me the opportunity to really put over some music that was personal to me and amplified it to a wider context that made it accessible to people. If you listen to “Spider Web,” go back to my first album Skeleton at the Feast there’s a song in there called “Tompkins Square Dance ” and one of the motifs in “Spider Web” is derived from that. It seemed to me that, ok, it’s a natural progression, I can take something that would stand up on its own as an exciting, colorful, mysterious instrumental piece, and put it over drum machines, and sampled percussion, and you can make a song out of this. I think that a lot of the music that I do stands up, if it has integrity as an instrumental work, it’s a good candidate as a pop song. I’ve written songs, for instance, with Jeff Buckley, both of which started as instrumental pieces. I had them intact. I wrote them here sitting in this chair. Then gave them to Jeff, and he came back and he had lyrics and a melody put over them. But they originally started initially as instrumentals. The song “Grace” originally was titled “Rise Up To Be”

” and one of the motifs in “Spider Web” is derived from that. It seemed to me that, ok, it’s a natural progression, I can take something that would stand up on its own as an exciting, colorful, mysterious instrumental piece, and put it over drum machines, and sampled percussion, and you can make a song out of this. I think that a lot of the music that I do stands up, if it has integrity as an instrumental work, it’s a good candidate as a pop song. I’ve written songs, for instance, with Jeff Buckley, both of which started as instrumental pieces. I had them intact. I wrote them here sitting in this chair. Then gave them to Jeff, and he came back and he had lyrics and a melody put over them. But they originally started initially as instrumentals. The song “Grace” originally was titled “Rise Up To Be” and I finally recorded a version of it on the Paradiso EP. So, I don’t really see any difference. To me, if it works as a hypnotic instrumental, it’s a good candidate for a Gary Lucas-type pop song or avant-pop song.

and I finally recorded a version of it on the Paradiso EP. So, I don’t really see any difference. To me, if it works as a hypnotic instrumental, it’s a good candidate for a Gary Lucas-type pop song or avant-pop song.

FRANK J. OTERI: Do you notate the music that you do?

GARY LUCAS: I don’t. I actually rely mostly on my memory and also my tape recorder here. I do a lot of composing where I mainly improvise on the guitar and I will come up with motifs and chord progressions…If they give me a chill, I think they are worthy saving on tape.

FRANK J. OTERI: And when you work with other people, you obviously read music, because you worked with Bernstein. But when you work in the context with sidemen and bands that you put together…

GARY LUCAS: I teach them the stuff. I don’t write it out. I just show them what I want them to play, and then direct them. But I also encourage them to come up with their own parts, and their own feel. I’m not as dictatorial as Beefheart. Because with Beefheart, everything more or less had to be completely how he heard it in his head. And me I’m more open for the group and the people I’m working with, to bring their own thing to the table. And I think that’s sort of the beauty of working with other people.

FRANK J. OTERI: I want to talk a little bit about this notion of collective decisions in terms of the group. You started a

band that has sort of been on-again, off-again over the last 11 years called Gods and Monsters. Are the records of Gods and Monsters your albums with sidemen, or are they albums by Gods and Monsters.

GARY LUCAS: The early stuff could be looked at more like an album of sidemen only because from track to track we used different ensembles and players. It was recorded over a few years. And that accounts for that. However, Gods and Monsters is now finishing up a record and it’ll probably be the first unified, band album that I’ve made.

FRANK J. OTERI: And will it be released under the name Gods and Monsters, rather than Gary Lucas?

GARY LUCAS: It’ll be Gary Lucas’ Gods and Monsters. I think it’s important to keep the Gary Lucas only because they have these header cards in records stores – I’ve already got a bin at Tower…

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s interesting because Bad Boys of the Arctic was essentially a Gods and Monsters album but it doesn’t say that until you get inside.

GARY LUCAS: Yes, it was. Yeah, well you know. It was sort of a marketing decision and I thought having established the name Gary Lucas as someone whose records you could find in the rock section of a Tower Records, I might as well continue to use it. And when I toured it would always be Gary Lucas and Gods and Monsters. But I just thought the main thing was to hit on the name. Perhaps if we had just become Gods and Monsters, it would be what people would recognize, you know, as an identity.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now is Gods and Monsters a reference to The Golem somehow?

GARY LUCAS: Actually, no, it comes from The Bride of Frankenstein. It’s a line within this film, one of my favorite horror films, in which Dr. Pretorious, this notoriously mad scientist, tells Dr. Frankenstein about an idea to create a mate for Frankenstein’s monster, and he toasts and says, “To a new world of gods and monsters.” The film that’s out called Gods and Monsters derived its title from The Bride of Frankenstein because it was about the director James Whale who had done the early Frankenstein.

FRANK J. OTERI: To get back to this thing about the group identity… It’s your material; you are clearly the leader of this group. Now that it’s a power trio, do you see collective composition happening, or other people in the band contributing to the repertoire of the band?

GARY LUCAS: They haven’t so far. I’ve still maintained the control over that. I’ve been accused of being a bit of a control freak, and it might be true, but again, I’ve encouraged them within my song, to bring their own ideas to the fore. Now my drummer’s got his own band, he’s got a Blues band, the bass player plays with some other people…

FRANK J. OTERI: They both have very interesting backgrounds. Your bass player played with Modern Lovers, and your drummer played with Swans, and then also with La Monte Young who in some ways is a guru of this entire movement of “it-comes-out-of-rock-but-it’s-not-really-rock-anymore…so-what-is-it” music.

GARY LUCAS: Well, they’re great guys, and because of the wide perimeters of their experience in the modern music world, they’re able come to grips with what I’m trying to get across, perhaps better than people who are strictly rock players.

FRANK J. OTERI: When will this Gods and Monsters album be out?

GARY LUCAS: We’re mixing it right now. We’ve been in the studio for the last couple of weeks trying to finish it in time to get a Fall release but I have feeling it’s going to be delayed until January.

FRANK J. OTERI: What label will it be on?

GARY LUCAS: On the Knitting Factory Label. But I do have several other records coming out that are scheduled to come out in the Fall, and in a way this is good because I don’t want too many things coming out at the same time and perhaps cancel each other out – it’s a danger.

1930s Chinese Singers Other Vocal Heroes

GARY LUCAS: I’ve been working on an album of Chinese pop music of the 1930’s, a genre that I’ve always really loved. My first wife was Chinese, and I lived in Taipei, Taiwan for two years, so I had a background in appreciating this music. I was sort of goated into learning it on the guitar on the behest of my friend Ken Hurwitz who married his Chinese sweetheart in Chinatown a couple of years ago, and they asked me to prepare a some of transcriptions of this music for guitar.

FRANK J. OTERI: For their wedding?

GARY LUCAS: For their wedding in Chinatown, to please his mother-in-law who loved this music. It was a big hit. Lee Ranaldo from Sonic Youth was there at the wedding, and he was also very enthusiastic about this. It’s something that also the critics had picked up on – there’s an example of in on Evangeline. I’ve got this record coming out with Chinese vocalists – half of it is guitar versions of the songs, and some of it is vocal renditions of the songs, and it concerns two great divas of Chinese pop music, Chow Hsuan and Bai Kwong, who are not household names, of course by any means, here, but to the older generation of Chinese, they were superstars. Both of them had different approaches to vocalese. Chow Hsuan had a sweeter, higher pitched voice, the songs kind of remind me of Betty Boop going to Shanghai. Bai Kwong had a deeper, voice, kind of a contralto, really sexy and affecting.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now that you’re bringing this up, we talked about your guitar heroes, your composition heroes, and your poetic and literary heroes, but we didn’t talk about your vocal heroes and where you see yourself as a singer in this whole mix.

GARY LUCAS: Ah, I’ve developed my vocals to the point where I’m comfortable singing a few songs now. I was discouraged from doing this originally because people were like: “Just concentrate on your guitar.” And having had someone like Jeff Buckley in my band, I thought, “This is a hard act to follow.” But my vocals have been getting way more acceptance from the audience over the years. My heroes are people like Bob Dylan who was able to put all the pain and joy of the universe into his minimal vocal style. I like Lou Reed very much. Beefheart, although I don’t really think I’d take anything from Beefheart. Bryan Ferry, another vocalist.

FRANK J. OTERI: I was actually hearing Bryan Ferry in the vocals in your albums.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah. So you know, I think that these are people who I have enjoyed over the years.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s interesting that you also have a lot of guest vocalists also. I guess it was Bad Boys of the Arctic that had some fabulous female vocalists. Almost things that sounded like the Roches at some times.

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, actually, I have a record that’s being released in France in September, and it’s should be out in the rest of the world outside the U.S. which is like the best of my early Enemy band albums. And I was just now writing liner notes for it, and I was thinking about how great Dina Emerson is, she sang on “Exit, Pursued by a Bear ” and she was in my band for a while. She came out of Meredith Monk‘s vocal group. She really has a ferocious range. Also on that album is Sonya Cohen who is the niece of Pete Seeger, and she has a beautiful, clear, Roche-like voice

” and she was in my band for a while. She came out of Meredith Monk‘s vocal group. She really has a ferocious range. Also on that album is Sonya Cohen who is the niece of Pete Seeger, and she has a beautiful, clear, Roche-like voice . I continue to like to work with other vocalists occasionally. For the Gods and Monsters album I’ve been working on, I have Elli Medeiros who is a French pop star doing a track. She really brings a different kind of erotic quality to her singing which I really like.

. I continue to like to work with other vocalists occasionally. For the Gods and Monsters album I’ve been working on, I have Elli Medeiros who is a French pop star doing a track. She really brings a different kind of erotic quality to her singing which I really like.

FRANK J. OTERI: Does she comes out of the chanteuse tradition?

GARY LUCAS: Yeah, she’s Uruguaian-Parisian and is a very sexy woman. I definitely responded to working with her in a visceral kind of sense. Also on the record is a singer named Robin Wiley who I made the acquaintance of recently, who reminds me a bit of a country-ish, almost Dolly Parton-ish singer.

FRANK J. OTERI: And what kind of instrumental background are you going to mix with that?

GARY LUCAS: More blues and country, and I’m going to attempt a version of “Grace” with her singing it to see how that goes this week. She’s in L.A. right now. Robin is someone to watch, definitely. Richard Barone is also on the record. He comes out of the Hoboken, power pop sound of the new wave bands of the 80s.

FRANK J. OTERI: So are you doing any vocals on this album?

GARY LUCAS: Mainly, mostly. I’m doing 6-7 vocal songs.

FRANK J. OTERI: A

re all the tracks going to be songs?

GARY LUCAS: There are two instrumentals. I always feel that there should be two instrumentals on a record. And there might even be a solo guitar instrumental – I’ve got a back log of them as well. But it’s going to be pretty much a unified band album. The first album with a consistent rhythm section all the way through.

Marketing Alternative Music

FRANK J. OTERI: You have a very active Web site that has won all sorts of awards. How has the web helped you to promote your music?

GARY LUCAS: It’s basically functioned as an electronic billboard out there in cyberspace so that anyone interested in my activities can go to it and find out about me if they don’t know much about me. I’m lucky because I got in on the construction of this thing 4 or 5 years ago through a couple of my friends who are computer wizzes, I am not I have to tell you. I am also a little bit skeptical of ultimately the way things are going with computers. I’m very cynical of Napster and MP3 files, although I may well put an unreleased track on my site as an MP3 giveaway soon. I came out of a generation that really missed out on the computer mania. I didn’t really learn how to learn to operate a computer until recently. And more or less only to give and get e-mail which is what I think it’s good for. To me the idea of spending hours hunched over a keyboard to surf the net or to listen to music, does not appeal to me at all. I can see the advantages to it obviously, with an exchange of information in some professions. But for me as a composer and songwriter, it doesn’t really do anything other than to alert people to my gigs, to tell them I have CDs available, and merchandise.

FRANK J. OTERI: So do you sell CDs on the Web?

GARY LUCAS: I do, but you know it’s not really yet a significant component of my overall career.

FRANK J. OTERI: Is Enemy Records your own label?

GARY LUCAS: No. Enemy was a label that was active in the late 80s and throughout most of the 90s. They were based in Germany and they had an office in New York. They pretty much ceased to exist as a functioning label, they have not released any new artists, or records in about 5 years.

FRANK J. OTERI: But their albums are still in print…

GARY LUCAS: They’re still in print in the U.S., some of them trickle into Europe as imports. And they’re available still on Amazon and CDNow. I think it was a great label in so far as the guy who ran it, Michael Kanoe, took real risks in signing non-mainstream artists. When I was there, they had Sonny Sharrock, Elliot Sharp, Jean-Paul Bourelly… It was real guitar, experimental guitar. The catalog was very good. But he came up against what a lot of indie-recording companies have, which is how to really get the music in the marketplace, and promote it in the face of thousands of records being released every month.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well I think these labels, these experimental risk-taking rock labels really function the same way as contemporary classical music labels and avant-jazz labels. We are all in the same situation. And interestingly enough, I think our audiences are the same. I wanted to ask you an audience related question, who do you think your audience is?

GARY LUCAS: From what I gather, many, many different kinds of people. I don’t think there’s a coherent demographic to it, other than people who are bored with what’s out there. ‘Cause I think most of it is crap, and my fans would agree. I think it’s people who are like seeking something more diverse that’s not idiomatic to genres. I got fan mail recently from fans in New Zealand, I don’t know how they discovered me, and they like the Jewish stuff. And they said, “Oh my Grandparents adore this record.” So I know there are some elderly people who are into it. I get fan mail too from young kids who discovered me when I played in France last time, some really young fans who stood in front of me, and staring at my fingers while I was playing. So they’re guitar freaks, they’re new music freaks, they’re Jewish music freaks. It spans genres, like my music; it spans types of people. I couldn’t really say that it’s one particular segment of an audience. But they’re out there. It’s how to get to them. That’s the question. Hopefully the Web site is one way that people who like what I do would at least be clued in to what my new releases were.

FRANK J. OTERI: All I can tell you is the first bug that got me thinking about this interview was that it was really exciting for me to be in Tower Records and to see Improve the Shining Hour next to Luscious Jackson in the Rock section. I thought “yes” because there it was this album that’s so all over the place and that’s so experimental next to mainstream pop music.

GARY LUCAS: That’s amazing. I feel lucky that way. See I never, as much as I’m identified as a Downtown player, I’m not your typical Downtown musician in so far as that I like pop music and I embrace it. I try to make popular music. I don’t try to limit myself to Downtown. On the other hand, I hate formulas, so I’m always trying to subvert formulas. I just couldn’t knuckle down to make a real, schmaltzy pop song that didn’t have some Gary Lucas twist in it. Anyway, it’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at. Uptown, Downtown, let’s get rid of these labels. Beefheart had this record called Lick My Decals Off, Baby, which he said meant “get rid of the labels.” And I think that’s important. Anyway, I will continue to try and reach out to a mainstream audience without actually making mainstream-type music because my experience is that once people hear what it is that I do they like it. It’s very user-friendly. It’s big on melodies. I like melodies; it could be going back to my parents playing Broadway show tunes in the house. And I like noise too. So in between these extremes of my experience, hopefully there are areas in there that all sorts of people can pick up on. And yet in a crafty sense I never try to aim at one particular market. So it’s a blessing and a curse. On one hand I get to really put my feelings on display, I get to play what I feel, and I like all these kinds of genres, but on the other hand it’s a bitch to market. It’s like how to go after what market, what niche. I don’t really know what niche I want. Some people have called it world music for God’s sake.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well it’s all world music unless it’s created in outer space. (laughs)

GARY LUCAS:

Well there you go, that’s right, I like that. I’m a one world-er that way.

A NewMusicBox Exclusive: Gary Lucas Plays

|

|

“Animal Flesh”

2mins 25secs – 1.7MB

Play |

“The Songstress on the Edge of Heaven”

2mins 28secs – 1.7MB

Play |

|

It is perhaps poetic justice that concurrent with our issue inspired by the winner of the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in Music that Bridge Records has released the world premiere recording of the Pulitzer winner from 1999,

It is perhaps poetic justice that concurrent with our issue inspired by the winner of the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in Music that Bridge Records has released the world premiere recording of the Pulitzer winner from 1999,

Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20.

Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20.