Saturday, December 18, 1999

American Music Center, New York NY

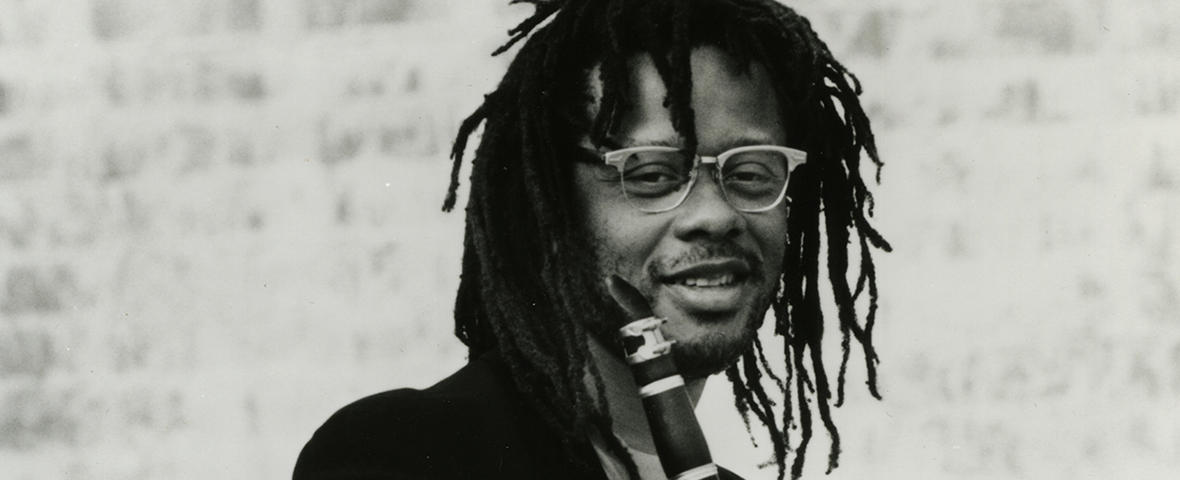

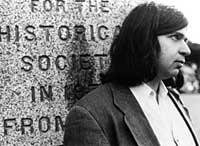

Don Byron – Composer and Clarinetist

Frank J. Oteri – Editor and Publisher, NewMusicBox

Nathan Michel – Assistant Editor, NewMusicBox

Interview transcribed by Karyn Joaquino

Venue, Audience and Genre Expectations

FRANK J. OTERI: I am really glad you made it, and it’s a pleasure to have you here. I’ve been wanting to do this forever, and ever since I first picked up Tuskegee Experiment years and years ago, and heard you live at the Knitting Factory many, many times, and this whole thing was actually provoked by a comment you said at the Knitting Factory when I heard you there, I think this must have been in like ’94, ’95, this goes a while back. You made a comment that you loved playing at the Knitting Factory because you felt you could play what you wanted to play there. You felt that you could do what you wanted to do, express yourself in your music in ways that you couldn’t in other places.

DON BYRON: I felt like that at the time.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, I wanted to explore that comment and really talk about how where a musician plays, whether it’s in the studio, or a live venue, a concert hall, an outdoor festival, a jazz club, other kinds of clubs, how that affects what you play, and what audience expectations are, ’cause you’ve done it all.

DON BYRON: Yeah, but, for example, I mean, on a jazz side, although I’ve won all the polls and all the prizes, it’s still kind of bandied about whether I should exist or not. That’s still like in question, whether I should be allowed to exist and do my various projects. So, a lot of times, when I’m playing in those places, I might be internally trying to come off like I know a lot of stuff about playing chords. Whereas I might play just as many chords if I wasn’t feeling that, but I also might play some other stuff.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: I would say that I’ve had to really sit on the fence between all of the stuff that I want to do and the fact, and just face the fact that even though I’m as much a downtown artist as any of the white downtown artists, that I’m essentially on the jazz beat, and what is normal for African-American musicians in the jazz beat is to do this kind of straight-ahead thing, and if you’re not doing it, the reason that you’re not doing it is because you’re a bad musician and you can’t play. I don’t really see the downtown cats, especially at this point, now that their thing is strong, I don’t see them going through that. They’re not subject to, you know, can they play the shit out of rhythm changes at breakneck tempos? Nobody’s doing that to them; they’re just doing what they want to do. And that I’ve been addressing for a long time. At one point [Peter] Watrous gave this incredible review to Braxton. It just wasn’t based on anything because everybody knows the kind of music Braxton’s playing. It’s not even applicable to question if he could play straight-ahead jazz.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, it’s almost saying, you know, could Elliott Carter write like Mozart?

DON BYRON: Exactly. Or could Elliott Carter write like Thad Jones… you know what I mean?

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: So, it’s almost like, you’re not really giving the black musician the full respect that he is something other than a jazz musician.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, that’s the thing. We have these words, we put these labels on things, and whenever we put a label and try to define something, we limit what it can be. Now, we’re sort of stuck with this word ‘jazz,’ for better or worse, just like we’re stuck with the words ‘new music’ or ‘classical music,’ but nobody really knows what any of these terms mean anymore.

DON BYRON: Well, they don’t mean much, except that all of the people that write for them, and all of the outlets in which you hear them, believe they have an audience that is something.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: For example, I wrote this on the Blue Note website, I think that in jazz, especially since the Wynton era, there’s been this kind of set life pose. Now, you know, I know a lot of these young lion guys, especially the first group of them. We were all going to Berklee and New England and stuff together. So I knew Smitty Smith, and Jeff Watts, and all of these guys that are involved in that. And I know that they had other interests. Someone like Greg Osby has been really true to all the things that he’s been interested in. But some of these guys, you know, they like some rock and some funk as much as the next guy, but they know that they can’t play it. They know that because they’re on this jazz beat they’re in this thing where they can’t do everything that they’re interested in, or maybe from their perspective, they’re getting paid doing what they’re “supposed to be doing,” quote unquote, so they just don’t do anything else. But, for me, I think the clarinet, and both the wide-openness of it and lack of opportunities ready-made in contemporary improvised music, have led me to do just whatever I felt like anyway, because the clarinet is not, you know, you don’t see people startin’ up, you know, burnin’ straight-ahead, post-Blakey things and say “I need a clarinet player today.”

FRANK J. OTERI: Right. It’s not the cliché. It’s not the saxophone; it’s not the trumpet.

DON BYRON: It’s not the saxophone or the trumpet.

FRANK J. OTERI: Yeah. And that’s really the cliché. It’s like the way people perceive the violin or the cello in classical music.

DON BYRON: It’s the thing. But, you know, the clarinet is not part of that thing.

The Clarinet

FRANK J. OTERI: That’s actually interesting to me, because in the early days of jazz, the clarinet was a big deal; think of somebody like Johnny Dodds, and even through swing, you know, with Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw and those guys, and then, when bop came along, the clarinet kind of disappeared.

DON BYRON: Well, the Goodman thing is really crucial in where the clarinet went. It’s crucial in the jazz thing. It’s crucial in the classical thing. The Goodman thing is a big thing to American clarinet playing, ’cause he’s the original Wynton guy. He’s the original guy that did that. And the clarinet pedagogy essentially has been fairly tight, giving information to people who might play jazz. The fact that I can play clarinet at the level that I can play it meant that I just moved from teacher to teacher until I knew what I needed to know about sound and technique. But there were lots of people that were not gonna give it up. And part of that is the Goodman thing because here’s a pedagogy that was putting itself together earlier this century, there’s no, you know, until you get to the classical period, there’s no clarinet, there’s no Baroque clarinet, there’s clarino, and you know, stuff that really doesn’t count, I mean, even if you hear some historical recordings of what clarinet virtuosos sounded like at the turn of the century, a lot of these cats couldn’t play now. They couldn’t even play. So, it’s a thing within itself, the classical clarinet pedagogy is a thing, is a work in progress. And then there were the three different schools. Essentially, the French, the German, and I think American clarinet playing is a school that combines the best parts of the French and the German. But the Germans, I mean, you know, they’ve been playing with the reed upside down, you know, with the reed on top, not that long ago. You know, that’s how double lip clarinet evolved, because when the reed was on top, everybody played double lip.

FRANK J. OTERI: So originally with the Brahms clarinet pieces, it was played with the reed on top that way?

DON BYRON: They might have played with the reed on top.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now, the Goodman question, in terms of what a popular persona he was, in terms of shaping the public image of what the clarinet was, do you think that had an effect on the clarinet disappearing in jazz, in bop, and more progressive jazz, the free jazz movement in the late ’50’s, early ’60’s? I mean, nobody was playing clarinet.

DON BYRON: Well…

FRANK J. OTERI: Dolphy played bass clarinet.

DON BYRON: Well, there’s Tony Scott.

FRANK J. OTERI: Tony Scott, right.

DON BYRON: Tony Scott was a bad cat. I mean, for me, he’s the greatest. For me… Tony Scott and Jimmy Hamilton, they’re the greatest. But… A few things happened. Essentially the swing era is a time when the clarinet wasn’t written in. There was a whole slew of bandleaders who were clarinetists. The Ellington thing was the best-integrated use of the clarinet. But when you get outside of the Ellington thing, it’s a double for most of the cats in the band.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right. They play saxophone.

DON BYRON: The clarinet isn’t even a part of the voicings. He’s just over the top. The clarinet players were the most, you know, if you, after Shaw and Goodman, you know, there’s not much more, in terms of that level of exposure. So that would be associated with some cornball stuff, by some cats that were doing be-bop. On the other hand, I heard a tape of Charlie Parker practicing along with some Benny Goodman 78’s. It’s bad, too, it’s like, oooh.

FRANK J. OTERI: And Charlie Parker’s playing clarinet!?

DON BYRON: He’s learning… No, he’s playing saxophone.

FRANK J. OTERI: Oh, he’s playing alto saxophone.

DON BYRON: He’s playing on saxophone, but he’s learning what Benny Goodman played.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: You know, Benny Goodman, he’s a funny guy. And so many of the important works of this century on that instrument were written for him, you know, specifically or vaguely. From all the jazz-influenced stuff to the Bartók Contrasts. I mean, that’s all Benny Goodman music.

FRANK J. OTERI: And then the Copland Concerto.

DON BYRON: Yeah, the Copland Concerto.

FRANK J. OTERI: …Stravinsky and Bernstein.

NATHAN MICHEL:The Stravinsky concerto was written for Woody Herman.

FRANK J. OTERI: …That’s right!

DON BYRON: But then, Goodman recorded it. It’s interesting that while the clarinet pedagogy doesn’t directly dis Benny Goodman, everything that he stood for has become the antithesis of academic American clarinet playing: kind of soupy tone, vibrato. I mean, when I came up, you know, just going to conservatories and stuff, you couldn’t play with any vibrato. None. That immediately put any brother in the ‘he’s a jazz musician’ thing. That was just where the pedagogy took it after this guy, you know, did some things just tonal-wise and technical-wise that they didn’t like. So they just took it to that place. And yet, a lot of people who have been through that pedagogy emulate him. Or want to play what he played. You know, “Sing, Sing, Sing” is the highest piece of

jazz thing that they could think of doing. So he’s kind of ever present, he’s someone who exists in my life every day in one way or another. And you know, I don’t really like the way he played that much. Not that much. I think he was strong at what he did, but I think Buster Bailey was really the cat who played that style who was really interesting to listen to.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now talking about how the clarinet works in the context of other instruments, in combination, what do you think is the best combination to have with clarinet? I noticed on your albums that you don’t really have other horns generally featured. I know that Music for Six Musicians features a cornet, and some of the larger bands feature other wind instruments. But you seem to like to play with guitar, piano, bass, drums, you know, not other solo horns.

DON BYRON: I tend to like chords. I’m interested in harmony a lot. On the other hand, you know, now I’m playing a lot more with trumpets. I mean, the Six Musicians thing is not coincidental; it’s my favorite band…

FRANK J. OTERI: I love that record. That’s actually my favorite record of yours.

DON BYRON: It’s a record that could have been made better. It’s just composition, you know, it’s not a playing record. So, these jazz slugs, they didn’t really understand what I was getting at. But, you know, I love a good trumpet player. But somehow, I went from being in school and really hating the guitar to working with all of the great guitar players of my era. I count Vernon, Frisell, Arto, Dave Gilmore, Ribot, one after another. And I feel really privileged to have done that, ’cause they didn’t question anything about whether I could do something for their music, you know. It wasn’t: “I don’t know, the clarinet could be cool, maybe,” and in Frisell’s case, he played clarinet. So there’s lots of times on his records and on mine, where if we’re playing, it’s really hard to tell…

FRANK J. OTERI: Yeah, it really sounds like 2 horns. But sometimes your clarinet even sounds like an electric guitar, I’m thinking of some of the tracks on Nu Blaxploitation, which Frisell doesn’t play on…

DON BYRON: Well, that also has to do with what I’ve tried to do with lines and playing, just what I’m trying to play, which is to integrate into the instrument more of the things that make a contemporary player effective, and so… Like a few weeks ago, I did this Carole King gig at MSG. I mean, it was unbelievable. But, you know, it was mostly all the Saturday Night/Paul Shaffer-type of cats and for one or two tunes they had some jazz musicians. And I think, you know, all Paul Shaffer knew about me was that I could play some klezmer music. But when he gave me a chance to solo, it was obvious to him that I had learned all the Junior Walker shit that he knows. And so he said, you know, “I had never really heard anybody play that on the clarinet.” And, it’s just like, that’s American, you know, why does what you play on the instrument have to be tied to what everybody else plays, especially when what’s been played on your instrument isn’t even vaguely contemporary, it has no relevance to anything now? So, I’ve just tried to, you know, everything that I’ve learned I learned on the clarinet.

Klezmer

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, this gets back to this whole question, of, you know, how your chosen instrument has shaped your own career and your own stylistic inclinations, the fact that you keep breaking boundaries. Every single recording is tackling another genre. Now, you mentioned that Paul Shaffer knew about the klezmer thing. That’s a genre where the clarinet was a really important instrument, back in the teens and ’20’s. And then klezmer kind of disappeared, except for Mickey Katz in the ’50’s and there was really nothing for a long time and now there’s this big revival. Your work predated that, to some degree.

DON BYRON: Well, not exactly. The klezmer revival kind of started in the mid- to late- ’70’s. It was basically three bands. It was Andy Statman, Henry Sapoznik’s Kapelye, and the Klezmorim. And so the Klezmer Conservatory Band was like the second wave of that, and then I was in that. So it certainly predates… my involvement in Jewish music predates all of this Radical Jewish Culture stuff.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right, right.

DON BYRON: In fact, that radical Jewish culture stuff was probably a reaction to the popularity of the Mickey Katz album. But I give it up to some of those guys, whether they can play or not. I mean, Andy Statman is a very good musician, Henry Saopznik not so much, the Klezmorim are kind of not even together, and when they’re together they have a total different pool of people, I don’t think that David Julian Gray and those cats are all in it. But, they were really the people that revived the music, and, you know, I give them some credit.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, what got you interested in the whole klezmer thing?

DON BYRON: Nothing. I mean, I was at New England, and Hank Snetsky, who was a teacher in the Third Stream at the time, was putting together a klezmer band for a concert of Jewish music, that was like a Hillel benefit that they were having at NEC, and, you know, among clarinet players who could understand chords, who improvise, who have some fluency on the instrument, there was, you know, just like now, there was nobody, so I was the only person to ask, and, you know, all of a sudden, we had gigs, and all of a sudden we had a band, and all of a sudden we had to get one set together, and two sets together. We really didn’t have time to think about whether the music was hip or cool or anything. We were just about getting the music together. And then, you know, certain qualitative differences in, you know, song structure, chord structure, the fluency of soloists, the quality of ornamentation became evident to us. But I think the first little blush of our work in that music was just kind of just breathless, you know, we’ve got to get something together. The only person I think you would know would be Frank London, who was in that group.

FRANK J. OTERI: He’s part of the Hasidic New Wave.

DON BYRON: Yeah, and he’s in the Klezmatics. So we all started playing klezmer music on the same day, I mean, you know, he’s in a whole trip now. I mean, you know, we almost literally started playing klezmer on the same day.

FRANK J. OTERI: And Andy Statman originally began as a bluegrass musician.

DON BYRON: Yeah, which really affected a lot of his output. I mean, my criticism of, like, the first bunches of those cats, and I think the Klezmer Conservatory Band’s angle on those cats was that they had some single line stuff, but no orchestration, no chordal understanding. He was a lot better than Sapoznik’s group, which if there was 4 chords in the spot, you’d get one, maybe. But Statman was the best musician of those three bands. But then things about his band were more bluegrass than klezmer. Like he never, for a long time he never really developed a drum, which, to me, if you’re doing klezmer music, there’s a lot to know about klezmer drums, as much as there is to know about Latin drums. And that was the first day that I did when I wanted to put together my thing, was put together a drummer and work on the theory of how to play Klezmer drums.

FRANK J. OTERI: There was a gig I heard with Statman at SummerStage in Central Park, I guess it was summer before last. This strikes to what we were talking about at the very beginning of our conversation. It was very interesting musically, it was this sort of free improv, it was really out there, Art Ensemble of Chicago-type improv.

DON BYRON: He’s into that…

FRANK J. OTERI: I loved it; I thought it was neat. But it was an hour-long gig and they did only 2 pieces. It was live in Central Park, and people were coming there thinking they were going to hear a klezmer band, and they were opening for the Del McCoury Bluegrass Band. And I think the audience totally didn’t get it. And as a result, I think it was a poor gig, even though the musical ideas were really interesting.

DON BYRON: Was it a poor played gig? Or a poor gig?

FRANK J. OTERI: It was a poor gig in the sense that there was no rapport between his group and the audience. There seemed to be a total disconnect. And it was a shame, because, I think the audience just was not prepared for what they were getting. And that harks back to what we were talk

ing about before, this question of how does where you’re playing affect what you’re playing.

DON BYRON: Certainly if the audience doesn’t like the shit that you’re playing! [laughs] We don’t have to expound on that.

The Downtown Scene

DON BYRON: When I discovered the Knit… Greg Osby turned me on to playing at the Knit…We played a duo concert, and that was the first time I played at the Knit. I saw what was happening there, like the Negativland stuff, you know, I was into all that… When I was in school, my little crew were into all these downtown cats: DNA, James Chance and the Contortions, Pere Ubu… You know, we liked that kind of stuff. So I knew all these cats’ work. Then you could pull off some jazz stuff. Then you could pull off, you know, whatever you wanted to pull off. And there was an excitement about it. So, to me, it was what I refer to as kind of an objective form, which, you know, classical music on paper is an objective form, but obviously, it’s not. So it seemed like a place where people were just doing whatever they needed to do. And then, miraculously, you might have a bunch of reviewers in the audience. It was serious. And yet, there was a freedom to it. I don’t think it’s like that anymore.

FRANK J. OTERI: But now, the weirdness and the outness is an orthodoxy in and of itself. You’re expected to play a certain way there too, at this point.

DON BYRON: Yeah, I guess. I mean, I wouldn’t know. The funny thing about the old Knit was how many people hung out. You know, the old Knit, when the Gulf War started, I went to the old Knit, I was living in the Bronx, I went to the old Knit, if I was going to go, if there was going to be some terrorist shit, it was my neighborhood bar. I was friends with the bartenders. I was friends with the people who worked there. I was friends with the other musicians. And it was a scene where the musicians were listening to other musicians. You know, everybody, almost everybody who was of any kind of legitimacy could come in and out of the Knit for free the way the jazz cats would come out of Sweet Basil’s and go to the Vanguard. And so, it was an unusual time when you could hear a lot of stuff. Sometimes, you know, stuff in its birth stage, sometimes really developed stuff, but you could just hear a lot of music. And I just thought it was a wonderful time. In a lot of ways, it was my undergrad. You know, my undergrad, my real undergrad, was a thing, but there was another quality to the old Knit period that had a lot of sweetness to it and a lot of camaraderie, there was a lot of camaraderie among the cats, which, I think there is some, but it’s not around a place.

FRANK J. OTERI: Are there any places anywhere in the country that are like that now, that are these hotbeds of activity?

DON BYRON: Wow, I wouldn’t know, ’cause, you know… I mean, I think, depending on what kind of music you play, I mean, there’s Hothouse in Chicago, which is for the AACM cats, and all of them Vandermark-type cats, they have a little scene around little joints in Chicago. There’s nothing happening in L.A..

FRANK J. OTERI: They have this place called the Jazz Bakery…

DON BYRON: The Bakery is a much more conservative place. But I know that the Knitting Factory is opening in L.A. They’re trying to do L.A. and Berlin. Berlin doesn’t need a Knitting Factory, ’cause the Quasimodo is a pretty progressive place, and the A-Train, the 2 clubs that people play at are, you know, they’re pretty open-ended.

FRANK J. OTERI: What about a place like Tonic, here in the city? Have you been there?

DON BYRON: Yeah. There’s a scene around Tonic. I’m just a not part of it. I mean, I don’t live in New York City anymore. When I lived in the Bronx, or I lived on Ludlow Street, you know, I hit these places everyday. Now I really can’t say that my musical life is based on that kind of connection to all these other guys. It’s not really based on that now. I mean, I have my crew, and you know, usually they’re playing something that I wrote, and it’s, it’s just a different time.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, in terms of this whole question, then, of composition, on your albums, they’re mostly your compositions, but you do some very, very interesting things with other people’s compositions, everybody from Ornette Coleman to Jimi Hendrix, there’s a Beatles tune on your most recent album. And it’s very clearly your voice through all of it. And I was listening, I laughed out loud last night when I heard your version of “If Six Were Nine,” the Hendrix tune, and you did this thing with the Turtles‘ song “Happy Together” on your solo.

DON BYRON: Well, you know, that just has to do with the little vamp at the end. There are only three tunes that I could remember that had that vamp. One of them was “Cherokee People” [a.k.a. “Indian Reservation“] by Mark Lindsay, you know, like Paul Revere and the Raiders, “boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boo doo.” You know, I just had that feeling and then that one. But you kn

ow…

Hip-Hop And Racial Politics

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, it’s making those connections which makes your music so fascinating. Being open to the influences of the different genres. You know, getting back to Nu Blaxploitation, I mean, that was a controversial album in some circles, because here you were saying, okay, well, hip-hop is part of my vocabulary as well, and…

DON BYRON: I don’t consider that record hip-hop at all. Not at all. I mean, and that’s not to say that you misperceived it. But it’s not, that’s not what we were doing exactly. Because, you know, you can’t read hip-hop. You know, you could sit down. You know, you got a brother like Sadiq talking about Foucault and shit like that, I mean, these hip-hop cats have a pretty limited world view.

FRANK J. OTERI: Not all of them.

DON BYRON: Not all of them, but you know.

FRANK J. OTERI: Someone like Chuck D can be a pretty erudite…

DON BYRON: Well, Chuck D is trying to be a figure in a larger kind of way, but I think, you know Sadiq is a poet. I mean, even among, you know, real grass roots people, poetry and hip-hop are different. Black poetry is really, you know… obviously there’s been an impact on it. But I wanted a level of poetry that I could stand to read. You know, that, like, I think that the real tip-off with Nu Blaxploitation and the poetry in it was that it was complicated enough that people would hear it once, totally get the wrong idea about what we were saying, which like, if you’re reading some poetry or listening to it really carefully, you get to all these double meanings and things like that, you know, that’s the pleasure of poetry.

FRANK J. OTERI: But in the sense where it was like hip-hop, in that, to use Chuck D’s phrase, it was a parallel to CNN. You were talking about stuff that was going on right then and there, the Louima case was in there.

DON BYRON: In that sense, yeah.

FRANK J. OTERI: And it was really topical, and really, you know, direct.

DON BYRON: You know what was really great, when we went to England and everybody wanted to talk about how we were dealing with the Princess Diana thing, that was hilarious. I mean, I’m so glad that I did that at that point because it was just, it just made me feel like I did the right thing. Even when people didn’t agree with us. Just what kind of conversations came up between me and just normal people about what we were trying to say, and how they had seen the whole thing come down, and their feelings about this and that.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, in terms of the whole political thing, a lot of your albums don’t have vocals at all, yet the titles still deal with political issues. And how do you feel the music reflects the titles of what you’re playing?

DON BYRON: Well, when you’re dealing with instrumental music, unless you want to get really Wagnerian, like this little line is this gnome, and this, you know, I mean… I think the feeling, say like, you know, one of my favorite pieces on the Six Musicians is the Sharpton piece. Now Sharpton to me is a figure who is both an incredibly good and necessary person to the black community, and someone that fucks up every once in a while. He’s not perfect; his hairstyle is abominable. He’s not someone that, like when you see Jesse Jackson, there’s a stateliness to Jesse Jackson, you know, and they’re both reverends, but you know, Sharpton’s stuff does not have the Teflon thing to it. But the tipoff with Sharpton always is for me, that when people say, he shouldn’t be your leader, they never have anybody else. It’s like, who’s better than him? Who’s there? Do you think if somebody’s killed in Brooklyn we shouldn’t respond at all? Which is probably what they do think.

FRANK J. OTERI: That is what they think.

DON BYRON: So, for me, I took what little I know about the second Viennese sound, which is ambiguous but has the feeling of chordal movement, but certainly is ambiguous in terms of tonal center, and that’s the kind of piece I wanted for that thing. The other, I mean, just to think of pieces off that record…

FRANK J. OTERI: The Shelby Steele piece, which I love.

DON BYRON: Oh yeah, that’s a good piece of music.

FRANK J. OTERI: In fact, that was the piece you were playing live that night at the Knitting Factory when you made the comment about being able to play what you wanted to play.

DON BYRON: Oh yeah?

FRANK J. OTERI: Yeah.

DON BYRON: That’s a good piece of music. You know, I mean, it’s just, I remember the only really obvious thing I did, I quoted “Bells in England” in the bridge of it, just to say that what was happening with Shelby Steele was little bit of colonialism.

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughs] Right, right.

DON BYRON: You know, just internalized colonialism. Shelby Steele is a evil fuck. He needs to be killed. He doesn’t need to be killed, but he just …

FRANK J. OTERI: Publicly exposed.

DON BYRON: The whole phenomenon of black conservativism and forms that it takes, you know, someone like Stanley Crouch, it’s obvious what he’s doing. Shelby is slick. And he knows he can say something incredibly true, and say something so killingly false, within a whisper. He’s a very clever man, and very dangerous. And then, you know, a lot of people that have no contact with black people at all read him.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: And that’s their opinion on how shit would go, it’s based on him, and not, hmm… Why don’t you hang out with some black folks and then you can decide what your conservative politics on the subject should be, you know. But people read him instead of experiencing black folks. Like if I had Shelby Steele in the cab I was just in… You’ve got people coming in, you know, Russian emigres, people from different parts of Asia, and the first thing they know is that they shouldn’t have any respect for somebody of color that’s already here. No matter how long you’ve been here, or what your thing is, they know, it’s not even so much they’re scared of us, they just know they’re not supposed to give us any respect. And, you know, that’s what happened. ‘Cause I saw this guy, just his whole reaction when I got in the cab, he was like, “oh, no.” What would Shelby Steele say? I mean, what could he say? Ellis Cose has a great book, and it’s all, it’s full of little humiliations of conservative black guys, you know, guys in the military, and then somebody, you know, a private, like, vibes them for their ID. You know, these little humiliations really contrast the possibility of there being black conservativism.

FRANK J. OTERI: There was a line on Nu Blaxploitation that really stuck out for me that I thought was really poignant about how there are people out there watching sports figures on their televisions and those are the only black people who have ever been in their homes.

DON BYRON: It’s true.

FRANK J. OTERI: And that gets to this question of, you know, we were saying that Nu Blaxploitation sort of operates, it might not be a hip-hop album, but it operates on the level…

DON BYRON: It does. But I’m a little sensitive about talking about that album in those terms, because what I was doing when we were starting to put that together was feeding Sadiq the Rollins Band and Nirvana, and I’m saying, well, you know, this is not the most blackified sound in music, but this has a quality that we need. And you know, it was a very delicate balance, you know, to me, you know, a record like Six Musicians could have been made better. A record like Blaxploitation is perfect. So if somebody doesn’t like it, it’s not because it’s not good.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s because they’re closed to it.

DON BYRON: It’s just because they’re just not open to it. That record does everything that it’s supposed to do. Everything.

FRANK J. OTERI: I grew up in New York, I watched the news, I was around for all the crap that went down with Louima, and, you know, the whole Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas thing, so I know all those things. When I see your titles, I get the references. But if someone’s in Europe, or if someone’s from another city, or someone ten years from now may not get those references, whereas on Nu Blaxploitation it’s clear.

DON BYRON: Yeah, but if someone’s in Europe and you name a title after a girl and they didn’t sleep with her, how they gonna know what you mean either?

The Audience

DON BYRON: I think as an artist, your job is to define the smallest space possible. I mean, look at Robert Johnson, I mean, he’s just talking about himself. He’s just playing his stuff. And then the circle of people that connect with that expands. But to make real art, the space that you work in, for me, should be fairly small, to make populous music is to try to say that this big ass circle of people is who you’re making this music for. But I don’t get that feeling, you know, when I listen to a Carole King record, I don’t get the feeling that she’s trying to make a humongo pop record. This is a small space. This is, you know, from the clavicle to the clavicle. It’s not about, you know, then, whether people are gonna get to connect with that is hit or miss. And that’s where the industry kind of messes things up.

FRANK J. OTERI: Sometimes it gets in the way.

DON BYRON: Because to make real art, you have to, you have to be looking inwards, and really maybe defining small places in yourself, at different times different places

FRANK J. OTERI: So, loaded question. Who do you consider your audience to be?

DON BYRON: Gee whiz.

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughs]

DON BYRON: You know, I had a real problem for a long time, especially with the klezmer shit, because I think those people thought that they were my audience, but they really were Mickey Katz‘s audience, or they were klezmer music’s audience, you know, because a lot of those people knew my work, people that followed klezmer knew the Klezmer Conservatory Band, so it wasn’t, some of them it wasn’t just Mickey Katz. I think that I don’t really have one audience the way that some people do. I think there are some jazz people that give it up to me, I think there’re some new music people that give it up to me, I think there’re some people across different spaces of music making and music listening who give it up to me. You know, some Latin cats give it up to me. You know, some don’t. Some classical cats give it up to me, some don’t. You know, but…

FRANK J. OTERI: And it changes with each record.

DON BYRON: And it changes with each record, because for some people, you know, what I’m doing is really not relevant. For someone who’s into Bug Music, Nu Blaxploitation is not relevant.

FRANK J. OTERI: And that was the next record right after it, too.

DON BYRON: Yeah. I mean, it took a while to make that record but it was the next record. You know, I mean… But that’s not really unusual. I remember I was watching Bravo one day and John Waters was on for a couple of hours, and he was saying, you know, “Gee, you know, like Joe and Jane Blow in Indiana, they love Hairspray, so they’re going to check out Pink Flamingos.” [laughs] Surprise!

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughs]

DON BYRON: You know what I mean?

FRANK J. OTERI: Yeah.

DON BYRON: And I think… what makes it a little funny is that I’m more like a Johnny Depp-type of musician than a James Cagney, where you’re always going to get, you know what you’re going to get. If you didn’t want that, you wouldn’t get this cat. I’m more, you know, Dustin Hoffman back in the day, when he was just, you know, one time he’s a ninety-year-old Indian… But the real difference is that people check out different films all the time. People are very environmental about music, and they don’t necessarily check out all these different musics, all the time. You know, for somebody, you know, some white woman, who’s really conservative, who loves Bug Music, you know, she doesn’t own any Mandrill. She doesn’t own any. I know she doesn’t. She probably doesn’t have any Sly either. So, who my audience is, I mean, that’s, it’s just really tough…

FRANK J. OTERI: But in some ways, ideally, if someone’s a fan of Bug Music, you might open up some minds if they buy Nu Blaxsploitation, they might go buy a Mandrill record, or they might go and buy There a Riot Goin’ On…

DON BYRON: One of these websites, I think it was Amazon.com, where people could comment, some of the comments on Nu Blaxsploitation, I mean, some of the cats were like, “DON BYRON is keeping it real. Kumbaya. Go on, brother.” And then, all of a sudden, “this is the worst piece of crap I ever heard in my life.”

FRANK J. OTERI: I was actually reading those comments.

DON BYRON: Oh, man, one of them is so funny because it’s just so obvious, it’s just so obvious. It’s not even like, how many other things like that do you own? You know, it’s not, you know, “I have Sunny Ade‘s record and his record is better than yours.” It’s not that.

FRANK J. OTERI: Right.

DON BYRON: You know, it’s a fish out of water.

FRANK J. OTERI: How many people own the collected works of Raymond Scott as well as Fear of a Black Planet?

DON BYRON: Not too many… The Raymond Scott thing is somethin’ else. Now he’s developed an audience and it’s in the pocket of some kind of hipness.

FRANK J. OTERI: Now they’re re-issuing everything. They’

ve even re-released this record he did of music for babies…

DON BYRON: I’ve got some really off Raymond Scott stuff. I’ve got the baby thing, some big band thing, there’s even a record he produced of Bo Diddley. This cat was out there.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, the most interesting people always are. They don’t want to be boxed in by categories. The minute you put a label on something, you limit what it can be…

Live Recordings

FRANK J. OTERI: You’ve done one live album so far. There are fewer and fewer live albums out there.

DON BYRON: They don’t sell or at least the record companies believe that they don’t sell.

FRANK J. OTERI: Well, we’re living in the age of the producer. Everybody wants a record that’s produced.

DON BYRON: You can produce a live record. And one live record can be worse than another live record. They traditionally don’t sell. Now, the record you’re talking about…

FRANK J. OTERI: …No-Vibe Zone…

DON BYRON: That’s a thing that I really have a lot of regrets about…When I was on Nonesuch, the scenario was essentially that I made Tuskegee, then I made the Mickey Katz and when I made that record it just seemed to swallow up everything. It was like, I’d be playing with a group at the Vanguard, and you know, every pick in every paper would be saying that we were playing Mickey Katz even though we had Smitty Smith and David Gilmore, you know, I mean, the band had nothing to do with that, and we said that. And yet that band developed some incredible presto-chango-like shit that that particular band could do. And then, you know, on the Nonesuch tip, it was too jazzy for them. They didn’t want to go there, with me, even though people were going to the gigs, and it was like, damn. It’s too strong. So that record was actually made after the fact, but I wanted to make that record at the Vanguard during the period. I think we had three different one-week engagements.

FRANK J. OTERI: So that’s why you thank Lorraine Gordon in the notes?

DON BYRON: Because that is how the thing developed. Really, what happened, was when Bill Frisell moved to Seattle, and I couldn’t get him, you know, because getting him meant the expense of flying him somewhere and getting him a hotel room, I had to put together something that approximated the level of racket that…

FRANK J. OTERI: You got Gilmore, who is wonderful.

DON BYRON: Well, Gilmore is wonderful, but he’s different.

FRANK J. OTERI: Yeah. It’s a totally different sound.

DON BYRON: The Gilmore and Uri thing seemed to have enough racket for me. And then there was a whole thing where Ralph Peterson was not allowed to play at the Vanguard, because he did, he did one of his record release parties at the Vanguard, and Lorraine, who takes everything really personally that happens at the Vanguard said, “You’ll never play here again. You can’t play here.” So it was literally like, you know, Ralph, to me, is one of the smartest, best drummers ever. I mean, you know, and people, you know, the Fo’tet, these records that we made together, the impact of those records among the cats, a lot of times, when I’m interacting with young musicians, that’s what they’re talking about. I mean, those were heavy records, but we had a great, almost telepathic rapport, but, you know, I couldn’t bring him in, so then I worked with Smitty, the group came together, but, you know, even from the very beginning, just what that group could do, the ability they had to learn music. We were playing Sondheim, we played everything. I mean, it was a group that had the real gestalt picture of all the things that I was interested in. I could take the compositions that I was doing with Six Musicians and have them play it. I could take some Sondheim, some Ellington, you know, it really didn’t matter, I could play a Four Tops tune, and they would get to the twists and turns of how to mess it up, but still, you know, they could play anything.

FRANK J. OTERI: Why the title No-Vibe Zone?

DON BYRON: Because, like we were talking about before, to make that kind of music, you can’t be thinking about what it’s going to look like if you make that kind of music, you can’t be thinking, well, you know, Stanley Crouch wouldn’t approve.

FRANK J. OTERI: So you want to say, “this is not smooth jazz”…

DON BYRON: No, there’s nothing smooth about it. I think what was more being said with the title was just that this is a kind of music, and a kind of way of relating to music that doesn’t have anything to do with the kind of jazz mentality, that we’re playing one music, and that all this other music isn’t jazz, we shouldn’t take it seriously, the level of humor in it. ‘Cause it’s a funny… you know, I mean, that group was hilarious.

FRANK J. OTERI: So you would consider working with a vibes player.

DON BYRON: Oh yeah. You know, I used to play with Bryan Carrott in Rob Peterson’s stuff. No, it didn’t have anything to do with hating the vibes.

FRANK J. OTERI: And I would love to hear what Bobby Hutcherson would sound like with you.

DON BYRON: Yeah, and you know, I haven’t really interacted with a lot of those old famous guys, partially because they put you through a lot of shit, you know, in terms of money, and just being high maintenance. You know, I’ve been able to do what I’ve done with Jack because he’s a very nice person and you know, we’ve, I really didn’t approach him to play until I had, you know, a relationship that felt nice to him.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s strange, but the new record is probably the most straight-ahead record of everything you’ve done so far.

DON BYRON: Yeah.

FRANK J. OTERI: It’s really solid… But at the same time, just when you’re about to make predictions, then along comes a piece like “‘Lude,” which is just so out there. I love it. I wish it went on for more than a minute.

DON BYRON: Yeah, well.

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughs]

DON BYRON: You know, we were all so honored to play with Jack. The shit that he played was so profound, and yet, there’s a vibe that Frisell and I have about playing that’s just really kind of joyful, and you know, we might play any little spaces of information from any of the shit that we know, and I think that what we did was just apply that to Jack’s stuff, and Jack applied his stuff to our stuff. But what I liked about it was that, a lot of times when people play with these legendary cats, ’cause the jazz stuff is this kind of almost patriarchy shit: your connection to Miles, your connection to Keith, your connection to Wayne and Herbie, and you know. And then you kind of branch out from that. From Bill Evans, you know, depending, just all of these people are like branches. And I think what a lot of young lion cats did, when they play with Tony, when they play with someone like Jack, it’s like, oh, well, I’ll be Herbie, and you be Wayne, and you be Miles. I mean, even Wynton did that. You know, he even had a tune on his first record called “Ron and Tony”. And I just wanted to avoid that. I just wanted it to be honest. I had nothing to prove to Jack. And yet, you know, while I was making that record, I would just break down and cry, because to me, Jack’s Special Edition groups were some of the most meaningful groups in all of jazz, at the time that I was in school. It was the aesthetic of them, and the progressiveness of them and the smartness of them. I think he’s really underestimated as a bandleader. I saw Special Edition with Blythe and David Murray. I’ll never forget that. It was just like, whoa. And you know, individually, some of those cats, it’s like I could take it or leave it. It was just the concept of it, and the playing, and the swagger that the band had. The swagger. It was kind of like he took the stuff that the black avant-garde folks were working with, and just upgraded it to where it was really splitting the difference between, you know, some real straight-ahead stuff and some total free jazz stuff. But it was at, it was at a high level of that, it was such an interesting group. I liked the group better than, you know, I mean, hearing a David Murray group is such a different experience than hearing Special Edition with him in it.

FRANK J. OTERI: Any possibility of a live album with this quartet?

DON BYRON: Well, we recorded the last gig and the second set, I thought.

FRANK J. OTERI: At the Bottom Line.

DON BYRON: Yeah.

FRANK J. OTERI: I wish I could have been there.

DON BYRON: Well, the second set was slammin’. I mean, I loved it. I haven’t listened to it. Maybe the first set was slammin’ but I did feel good with the second set. It was pretty slammin’.

Stravinsky

FRANK J. OTERI: I was reading in your Blue Note bio that you’re working on a Stravinsky album? What’s that about?

DON BYRON: I’m going to record a whole bunch of Stravinsky, yeah, and try to avoid, you know, the obvious, like Ebony Concerto and Octet. You know, Stravinsky to me is so much a part of everything I write, just a sense of inner voicings, a sense of creating hocket, the sense of, just on so many levels, I mean, you know… I was at Manhattan School of Music, and I had a clarinet teacher who was really down with Stravinsky. She’d give me these parts to Movements for Piano and Orchestra and shit, I couldn’t make anything out of it. I mean that’s an out piece. You know, “here, practice this – [sings] eee umm uh eeee.”

FRANK J. OTERI: [laughs]

DON BYRON: You know, what was I going to make of that! But she laid that on me, and like a lot of really good teachers, she didn’t massage it or try to kick my ass with it. And then, just all of a sudden, I understood, oh my God – this is the shit. This is like, this is, this is, all this Apollonian shit – I get it, I’m in it, I’m there! And then, when I started plowing through these scores, just from second to second, I mean, one of my tunes is like 2 seconds of one of his masterpieces. I mean, he’s got shit that lasts 2 seconds. I could take a tune out of that and change it up, you know, and steal the shit, I mean, he’s incredible. And you know, he really, he and Eddie Palmieri were just at the whole objectivity question. To me they were the kings of that. Ed Palmieri back in the day… oh God…

FRANK J. OTERI: The Sun of Latin Music, what a great record that is.

DON BYRON: But, I mean, just the whole thing between the inside thing, and then what he was playing in his solos, it was just, oh, it’s so violent.

FRANK J. OTERI: He also does one of the best Beatles covers of all time.

DON BYRON: On Live at Sing Sing?

FRANK J. OTERI: No, on The Sun of Latin Music, they do a version “You Never Give Me Your Money.” It’s funny, too. ‘Cause it comes out of left field. They’re doing this whole montuno thing with it…

DON BYRON: He is so great. But, I mean, the two of those guys really, just in terms of my whole aesthetic angle, just that you didn’t really have to be some music, you don’t really have to be music. You have to learn it. You have to study it. You have to try to understand it, and really understand its inner workings. I mean, people study music but they often don’t understand it. You know, and Stravinsky understands so much music. Man, opera and all that pagan Russian shit, which filters through his music. I mean, when you see a movie like Shadows and Forgotten Answers, ’cause then you see where the shit is coming from, but, that he had a grasp of that on top of all the Rimsky-Korsakov stuff that he had. I mean, you know, you don’t need me to praise how heavy Stravinsky is because I’m sure that’s been done. But, you know, if I make a Stravinsky record, it’s not even like there’s going to be a whole bunch of blowing on it. But I think that some unusual people will be playing in it, and I think we’re going to have some tribute pieces by some contemporary composers. You know, we’re going to be playing, you know, I’ll even conduct an orchestra piece or two, maybe we’ll do Danse Concertante, as opposed to the shit that everybody else records, because this cat has so much slammin’ music. I mean, just totally, you know, if that was the only thing you ever wrote, you’d be a bad cat. But, you know, people don’t even know all this music.

FRANK J. OTERI: And once again, he’s somebody who was not afraid to change styles throughout his life, and not be locked into any kind of…

DON BYRON: Even the last period is so fascinating, you know, where he’s really writing serially, but it doesn’t sound anything like Schoenberg – nothing. I mean, he’s a bad cat, but that’s, when you develop your voice at that level it doesn’t matter what you do. And that’s what I’ve tried to do the whole time, is just say, well, my voice is this. My compositional angle on this Afro-Caribbean stuff is this. My compositional angle on this funk is this. You know, so that it’s not like I want to make you smile and play some funk. I want you to listen to my angle. And that’s the voice. The voice that he has is so strong it doesn’t matter what he plays. He could play a tango, he could play some jazz, not that that really sounds like jazz, but still, I mean, it sounded like, somewhat like some of the jazz he might have heard. You know, I mean, so much of his music. I love his choral music, oh man…

FRANK J. OTERI: Symphony of Psalms.

DON BYRON: I mean, the late, like really atonal choral music. That’s a pretty high level. And he sustained a level of innovation for so long. And that’s really unusual, you know, most cats, they hit a certain point, and it’s like, it’s just okay. You know. The Flood, bad piece of music! It’s a bad piece of music. I don’t know. I mean, for me. Nobody’s even checking that out. I can’t remember the last time I heard anybody doing that, The Flood.

NATHAN MICHEL: Olly Knussen has a great reco

rding.

DON BYRON: Oh yeah?

NATHAN MICHEL: It’s amazing. Yeah.

DON BYRON: It’s a bad piece of music. And the only recording I have of it is the TV thing that they made it for.

FRANK J. OTERI: We were at a luncheon, I guess it was about a month and a half ago with Robert Craft, who’s putting out a new Stravinsky edition. They actually recently found a solo clarinet piece that Stravinsky wrote for Picasso.

DON BYRON: Wow.

FRANK J. OTERI: He wrote it on a napkin and was really drunk at the time, and…

DON BYRON: How long was it?

FRANK J. OTERI: Minute and a half. I should get it to you. I’ll get a copy.

DON BYRON: You should!

FRANK J. OTERI: I will. I definitely will.

DON BYRON: You know, the Three Pieces … Because of my teacher, I had to play that shit. I might even have to play it on my record, but, it’s just, you know, I don’t want to be obvious.

FRANK J. OTERI: I’m sure whatever you do, it’s going to be extremely original, like everything else that you’ve done thus far.

DON BYRON: You know, we’ll see.

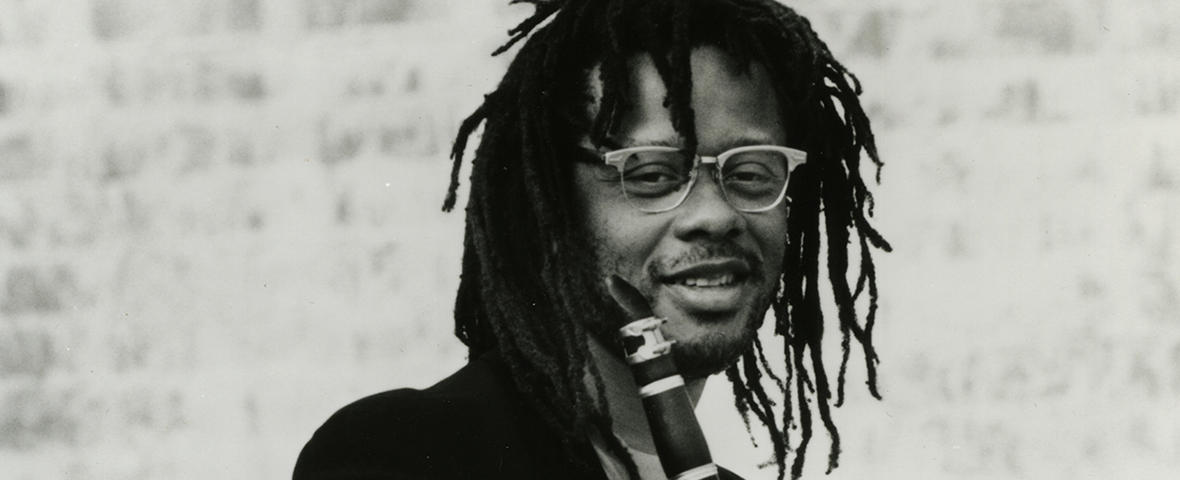

Biography

Don Byron has been consistently voted best clarinetist by critics and readers alike in leading international music journals since being named “Jazz Artist of the Year” by DownBeat in 1992, the year he startled the jazz world with the release of his widely acclaimed debut album, Tuskegee Experiments. Continually striving for what he calls “a sound above genre,” Byron has created a unique musical aesthetic in a wide range of contexts over the years.

Born and raised in the Bronx, Byron was exposed to a wide variety of music at home by his father, who played bass in calypso bands, and his mother, a pianist. His taste was further refined by trips to the symphony and ballet and by many hours spent listening to Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Machito recordings. Byron formalized his music education by studying classical clarinet with Joe Allard while playing and arranging salsa numbers for high school bands on the side. He later studied with George Russell in the Third Stream Department of the New England Conservatory of Music and, while in Boston, also performed with Latin and jazz ensembles. These diverse experiences fostered the clarinetist’s affinity today for the music of a broad array of artists including Igor Stravinsky, Robert Schumann, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, Eddie Palmieri, Henry Threadgill, Joe Henderson, Raymond Scott, Nirvana and Bill Frisell.

His artistic collaborations include performances and recordings with Frisell, Cassandra Wilson, Hamiet Bluiett, Anthony Braxton, Geri Allen, Hal Willner, Marilyn Crispell, Reggie Workman, Craig Harris, Steve Coleman, David Murray, Living Colour, Ralph Peterson, Mandy Patinkin and Daniel Barenboim, among many others.

An integral part of New York’s cultural community for more than a decade, Byron served for four seasons as artistic director for jazz at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where he curated concerts for the renowned Next Wave Festival, participated in BAM’s educational programs and hosted weekend jazz performances. Other special projects include his arrangements of Stephen Sondheim’s Broadway music, an original score for the silent film Scar of Shame and a string quartet, “There Goes the Neighborhood,” commissioned by the Kronos Quartet and premiered in 1994 at London’s Barbican Center.

He has performed at major jazz festivals throughout the U.S. and Europe, including North Sea, Umbria, Berlin, Paris, JVC and San Francisco. He was featured in Robert Altman’s movie Kansas City and the Paul Auster film Lulu on the Bridge for which he also wrote and performed music. He has composed and recorded the theme music for the Tom & Jerry animated TV series currently being broadcast on the Cartoon Network, and is currently working on scoring episodes of the comedian Ernie Kovacs’ pioneering television broadcasts of the late 1950s and early 60s. He is also preparing an album of duets with pianist Uri Caine and a recording of chamber works by and in tribute of Igor Stravinsky for Angel Records.

Byron has released a diverse array of recordings during the 1990s. Following his groundbreaking recording debut, Tuskegee Experiments (Nonesuch, 1992), Byron’s other projects include: Don Byron Plays the Music of Mickey Katz (Nonesuch, 1993), a tribute to the musically challenging and bitingly humorous works of the neglected 1950’s klezmer band leader; Music for Six Musicians (Nonesuch, 1995) which explores a significant side of his musical identity, the Afro-Caribbean heritage of his family and the neighborhood where he grew up; No-Vibe Zone (Knitting Factory Works, 1996), a vibrant live recording featuring his jazz quintet; and Bug Music (Nonesuch, 1996), his spirited showcase of the nascent Swing Era music of Raymond Scott, John Kirby and the young Duke Ellington based on meticulous and faithful transcriptions of their recordings.

His 1998 Blue Note debut Nu Blaxploitation is a wide-ranging musical meditation with his band Existential Dred that fulfills its promise to be a “genre bending experience” by featuring poet Sadiq Bey and rap icon Biz Markie in performances reminiscent of the spoken-word pieces of Gil Scott-Heron, Amiri Baraka and Henry Rollins. The CD also includes musical tributes to Jimi Hendrix and the 70’s funk band Mandrill. His newest Blue Note recording, Romance With The Unseen, featuring guitarist Bill Frisell, bassist Drew Gress and drummer Jack DeJohnette, was released on September 21, 1999.

“Mr. Byron has not only almost single-handedly revived an instrument that was pronounced moribund with the end of the swing era – since Benny Goodman, how many other major clarinetists weren’t merely moonlighting sax players? – He has also taken a scholarly approach to jazz without a hint of academic stuffiness. Every time Mr. Byron revisits the music of a neglected jazz figure or mixes hip-hop with jazz in a way that eluded the acid jazzers, he’s not only charting new musical territory but he’s actually an undercover critic trying to re-write the music’s history.”

-The New York Times