Often I’ve heard people metaphorically refer to working musicians as practitioners of the world’s oldest profession, usually by the most ubiquitous employers of freelance musicians, the parents of soon-to-be brides. But I’ve heard enough professional musicians discuss the vocation as such that I wonder just how old our profession is. According to the Jubalist philosophy of music history, animal husbandry is the oldest occupation, with music coming second (Genesis 4:20-21). However, there is enough evidence to suggest that music is a human activity that predates the concept of professionalism. However, our evolutionary trajectory for a long time points towards our becoming a commercial species, homo negotiorum, and music is now a commodity with its own subculture(s) of professional manufacturers, performers, composers, instructors, presenters, and mongers.

Those engaged in the music business today wear several of these hats at once and it has become commonplace to see self-produced CDs being sold at an artist’s public performances, something that was rare when I was starting out, forty years ago. Then the idea was that someone else took on the role of producer and distribution was handled by a “label.” I realized that I’m still adjusting to this jack-of-all-trades paradigm when I was in the recording studio last week, documenting the music of guitarist-composer-educator-impresario Omar Tamez at Brooklyn Recording, a fantastic recording facility in the Cobble Hill section of Brooklyn. (While not nearly as spacious as my all-time favorite, Systems 2, Brooklyn Recording’s equipment is every bit as good—even to the availability of a Studer 24-track analog recorder—and their offering of esoteric vintage amplifiers and electronic keyboards is superior.) The session was co-produced by pianist-composer-educator Angelica Sanchez and included music composed by her as well as by Tamez and myself. Percussionist Satoshi Takeishi rounded out the group and I look forward to hearing the final product after Tamez mixes and masters it in late December. Omar will be performing with trombonist Steve Swell at Roulette on December 6 in a concert of the music of his father, Nicandro Tamez, produced as part of singer-composer-presenter Thomas Buckner’s Interpretations series. Sadly, I’ll be in San Francisco preparing for my December 9 concert at Chez Hanny and will have to miss it.

More sadly, drummer Pete “La Roca” Sims, a man who exemplified a philosophy of music that ran counter to the corporate culture that established and disseminated jazz as America’s music, lost his battle with lung cancer at the age of 74 on Monday, November 19. Born April 7, 1938, Sims was probably best known as the original drummer in the John Coltrane Quartet (with pianist Steve Kuhn and bassist Steve Davis), a role he performed while Elvin Jones was indisposed in Lexington, Kentucky in 1960. Sims was a musician of great depth who also wore the hat of bandleader and was responsible for giving many of today’s prominent jazz musicians their initial exposure to the public. Saxophonist-composer-educator David Liebman wrote of him:

Before the advent of so many jazz programs … the question used to be …: “Who did you play with?” The inference was what “master” did you serve under. (Now the question is: “What school did you attend?”) Those of you familiar with my background know that I … put in a few years with Elvin Jones and Miles Davis…. But my first true employer was drummer Pete LaRoca Sims…. I spent … six months with him mostly doing a gig at a club … called La Boheme paying five dollars a night…. We ended that cycle playing the Village Vanguard on Thanksgiving weekend in 1969 … my first time there. I was substitute teaching in NY schools at the time to make a living…. For those six months every bass player and pianist in New York worked with Pete and me. He was my first teacher in all ways…. a brilliant guy who after being so disenchanted with the music business became a lawyer…. Coltrane had him before Elvin; he worked with Newk [Sonny Rollins]; Miles wanted him to join as did Herbie Hancock when he branched out on his own. Pete was one of a kind … a stubborn, brilliant guy who insisted on perfection. I will never forget the lessons he taught me, which I recite almost daily in my teaching. For me, Pete’s passing is in a sense like the passing of a father or uncle, meaning of all my mentors he was the last to survive.

The ellipses in the above quote omits Liebman’s explanation of “La Roca” (“The Rock”) as a nickname (bestowed on him during his years as a timbalero), but Liebman doesn’t mention in his eulogy Sims’ achievements as a lawyer.

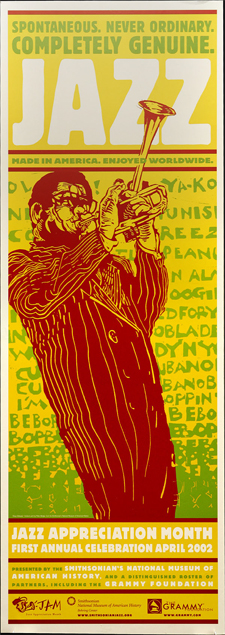

Possibly the most important of these was the role he played during the 1980s in assisting attorney Paul Chevigny in changing the oppressive cabaret laws in New York City. The laws were established in 1926 and targeted venues serving food and/or drink where jazz was performed, especially to the audiences comprised of a diverse array of skin pigmentation that congregated in Harlem, by requiring them to purchase a cabaret license or limit the number of performing musicians and/or “people moving in synchronized fashion” to three or less. Anyone working in a New York City nightclub had to have a valid cabaret card, which was controlled by the city’s police. If an entertainer didn’t have a card, he or she could not play any steady engagement in the Big Apple, which was defined as one lasting three or more consecutive days. The cabaret card requirement was dropped in 1967 (after Frank Sinatra wrote to the City Council that he would not apply for a card nor perform in NYC if he needed one), but the cabaret laws still stand today, although in a different form. By 1980, the laws stated that no wind or percussion instruments were to perform in nightclubs without the hard-to-get cabaret license. In 1987, these instruments were allowed (since an electric guitar, technically a “stringed instrument” could play louder than an entire big band), but the rule limiting the number of musicians to three was still enforced. Chevigny credits Sims with pointing out that the limit on the number of musicians placed the law in conflict with the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, since musicians had to re-orchestrate music originally intended for more performers, thus compromising their artistic vision. On this argument Chevigny was able to get the limit repealed, although to this day a license is required for establishments that allow dancing by three or more patrons on their premises. Still, it’s not hard to imagine that American music might be very different today if it weren’t for drummer-presenter-educator-attorney Pete “La Roca” Sims.

I remember well how, upon arriving in New York in 1977, certain nightclubs only had piano duos. The best known was Bradley’s on University Place, and the Knickerbocker Bar and Grill still features that instrumentation as its nightly entertainment. While the quality of the music coming out of these New York City establishments was nothing less than superb, the effect on drummers was devastating. I know several world-class drummers who were faced with leaving town or taking up a second career. During the brief time I drove a taxicab in the Apple, I saw many drummers doing the same: Tom Rainey, Newman Taylor Baker, and John Betsch were just a few. And another was Pete “La Roca” Sims. In a 2004 interview given to José Francisco “Pachi” Tapiz, Sims describes his early exposure to music as part of his family life with the profound story of how his uncle, Kenneth Lloyd Bright, a field director for Circle Records, made it possible for him to be present at a broadcast of James P. Johnson and Baby Dodds—which would have occurred at radio station WOR in 1947, when Sims was nine-years old! He also explains his five-year stint as a New York “hackie” as the pivotal experience supplying the impetus to take up law. But he never once mentioned the word “cabaret” in the interview or alluded to the possibility that regulations on the entertainment venues in the city were designed to make a career as a free-lance drummer difficult to pursue. Instead he blamed the genre of jazz-rock fusion as the focus of his “disenchantment” with the music business and dispels the myth that he retired from music to take up law.

Without mentioning names, Sims described how, after recording two albums of music with Middle Eastern and Indian themes, Basra (Blue Note, 1965) and Turkish Women at the Bath (Douglas, 1967), he was employed for several recording sessions that required him to play in a fashion he felt was inappropriate to his artistic vision. One such session required that he play “extremely repetitive and boring” straight-eighth note back beat and shuffle rhythms, “the basis of Fusion.” Another required that he supply a swinging feel to the straight-eighth note music of the Byrds, “(that’s Fusion again, folks).” The one name he did mention is that of Columbia Records producer John Hammond, who wanted him to record with “a great Jazz saxophonist” and “an East Indian singer.” Hammond wanted to include another drummer, one who played rock ‘n’ roll to provide what he believed would ensure commercial viability. Sims refused to work with the “Rock drummer” and “they sent in a couple of guys who looked like they wanted to break both my legs.” Sims stuck to his guns and the date was cancelled. Sims was now a “Bad Boy. Blackballed! Not to be hired. [His] calls not to be answered.” (Of course, I would love to know who the unnamed parties were, especially since it wasn’t long before saxophonist Ornette Coleman recorded an album for Columbia, Science Fiction, featuring the Indian-born vocalist Asha Puthli.) Indeed, there is a huge gap in Sims’s discography between 1967 and 1997. Fully 90% of the sessions listed are from the first ten years of his recording career with the major portion of the remainder recorded in the last year. In fact, only two recordings are from the 30-year hiatus: two private recordings of one song each, the first of which, recorded in 1974 (the other is from 1995) was released on a label appropriately called “Ironic.”

Pete La Roca, a. k. a. Peter Sims, led a life peppered with irony. His first recording as a leader, Basra has an eclectic mix of songs. He didn’t shy away from playing a feel-good boogaloo groove on its opener, “Candu,” which, along with the title track and “Tears,” is one of three originals on the album. Ernesto Lecuona and Marian Banks’s “Malagueña” displays saxophonist Joe Henderson’s virtuosity as does the classic rendering of Jerome Moross and John Latouche’s “Lazy Afternoon,” with Henderson’s altissimo tenor over Steve Kuhn’s lush piano voicings. But it’s ironic that bassist Steve Swallow’s “Eiderdown” became a mainstay of jam sessions and a “jazz standard” in its own right. La Roca’s next album as a leader, Turkish Women at the Baths (named after a 19th-century painting by Jean August Dominique Ingres) features seven Sims originals, one of which, “Bliss,” incorporates a psychedelic “slap-back” reverb effect popular at the time. One could interpret a sense of irony in the entire recording being reissued under pianist Chick Corea’s name (he, as well as saxophonist John Gilmore and bassist Walter Booker were on the date) on an album called, Bliss (Muse, 1973), if it weren’t that another one of Sims’ legal coups was to successfully sue either Corea, Muse, or both. Pete Sims’ final session as a leader, Swingtime (Blue Note, 1997), features Liebman as well as Lance Bryant on soprano saxophones. Mingus alumnus Ricky Ford is on the tenor saxophone and National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Jimmy Owens plays trumpet. Sims’s rhythm mates on the date are pianist George Cables and bassist Santi Debriano. I haven’t heard the entire CD yet, but I have heard excerpts that are promising and I plan to order a copy when I get to San Francisco on Saturday, even though the thought that one of jazz’s biggest labels, Blue Note, has outsourced its distribution as manufactured “on demand” is something I also find ironic.

Pete La Roca lived 15 years after the release of Swingtime, his final recording session as a leader

A strange twist of fate has added another element of irony to this post about Peter “La Roca” Sims during my research for it. Of course, I have to mention the irony I found in reading in his interview of how he abhorred the monotonous repetition of fusion drumming, but considered the motoric practice of playing bass lines comprised entirely of quarter-notes (“walking”) as “the greatest musical development of the 20th century (12-tone notwithstanding).” But when looking through website after website for something that didn’t keep repeating what I found unbelievable, that he would just stop playing music to pursue a career as a lawyer, I found one at Drummerworld that stopped me dead in my tracks. The myth isn’t dispelled, but reinforced by giving a date for his “return” to music (1979). There are three great excerpts from videos of La Roca playing with trumpeter Art Farmer (with guitarist Jim Hall and bassist Steve Swallow) as well as with tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins (with bassist Henry Grimes) that display his smooth time keeping and as yet unpolished imagination as a soloist. But there is also an audio clip just below the brief obituary that is label “Click Sound: Pete La Roca Sims.” When I clicked it, I heard a familiar quasi-second line pattern of Tom Rainey. Ironically, the sound clip was (and possibly still is) the theme and piano solo on Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “Have You Met Miss Jones,” performed by the Kenny Werner Trio on the CD, Guru (TCB, 1994). And it ends just before my bass solo!

Probably the greatest irony in the life of Pete Sims is that someone so articulate, capable, talented, accomplished, and respected by his peers came to be ignored by the industry. The 30-year gap in his discography, followed by another 15-year span of inactivity from his last year of major label recording until his death, speaks volumes about just how uninterested in musicians the music industry can be. Sims’s musical vision, like his playing, was direct, clear, and obvious. He was a sensitive improviser and, as the Art Farmer videos linked to above show, forgiving of the faults of his band mates—notice how Jim Hall, I’m sure without ill intent, interrupts the flow the 21-year old drummer’s solos by forcibly injecting his sense of the form of the tune into them. A stubborn Pete Sims could have pressed on and let Hall’s interjections fall to the wayside, but his dedication to musical teamwork prevailed and he deferred to Hall. The only time that I had the pleasure of seeing him play in person was at Birdland when it was still on the corner of 105th and Broadway. I don’t remember the exact year or who was in the band he was leading. But I do remember that everything he played was meant to serve the musicians on the stand with him, whether they were acclaimed masters or not. In the final analysis, it can be said that Pete “La Roca” Sims spent a life of service to his master, music, and not to the service of Mammon; something that should not be taken lightly when engaging in the second oldest profession.