Unprecedented Time

There is no doubt that we are in unprecedented times. Living through a global pandemic has tested and revealed so much about who we are as a people and what we possess as a culture. From the social battles that we have all watched boil over and spill out onto the streets, to the emotional battles that we have all waged within ourselves over this past year, we are struggling to make sense of what the future holds. And through it all, I have learned what many already knew: that art is like a weed – stubborn and persistent. Art will push on regardless of the circumstances, and I find it to be a transcendent privilege as well as a dire responsibility to stay focused on ways to continue innovating the arts without hesitation or compromise.

My personal experience in 2020 has offered countless peaks and troughs on the emotional roller-coaster ride of life, though peppered within have been some welcomed serendipities. Dating back to the fall of 2019, I was gearing up to work on a commission for a large-scale multi-faceted project, TIDES, that had been several years in the making and involved video/media artist Ian Winters and co-composer Wayne Vitale, both long-term collaborators of mine. We laid a foundation with concrete artistic concepts and interlaced composing strategies, but due to last-minute circumstances beyond everyone’s control, that foundation cracked and we ended up dividing the musical component of the project into two separate compositions: a sound installation was to be composed by Vitale and I was to compose a live piece, and both would accompany video footage and media created by Winters. I then took on the responsibility during a five-week window to compose thirty minutes of music for TIDES to premiere in late March 2020. Indeed, this would be the first new composition that I had undertaken since the birth of my first child in May of 2019.

The piece that I composed as a result, named Tides after the larger project, is a quintet for clarinet, violin, vibraphone, harp, and piano, and as one might have guessed, the March premiere was never to take place. After completing the music in February and hosting some preliminary rehearsals with the players, our last round of rehearsals in March were cancelled one by one until ultimately the Minnesota Street Gallery in San Francisco, where the premiere was to be held, cancelled the late March performance.

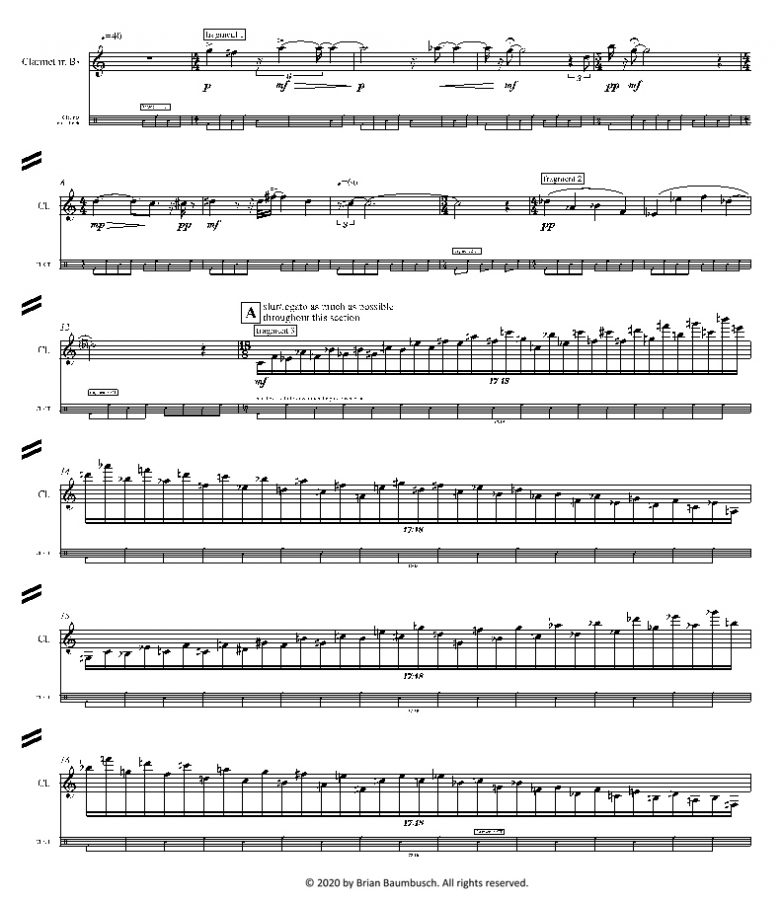

As I witnessed all of this playing out, I started to glimpse the peculiar silver lining that was specific to my situation. Over the past five years, much of the music that I have composed involves the use of multiple simultaneously varying tempos, or polytempo. In order to perform this music accurately, I tell the musicians that they are required to use click tracks in performance, something that isn’t always met with open ears. Because of the fact that each click track carries its own independent tempo stream, players often express the frustration that hearing the other ensemble members adjacent to them playing in a different tempo can hinder their ability to accurately follow their own click track. In the case of Tides, I started to develop a new level of complexity in the polytempo structures that I was using, in part because I had assembled a crack ensemble of some of the Bay Area’s finest musicians, but also because the music was designed to accompany video footage created by the lead artist of the project, Ian Winters. Because of the fact that film and click-track-music are both real-time mediums, I wanted to take advantage of the potential for hyper-synchronicities between the two. All of this served to make a live ensemble performance of this piece that much more difficult.

After the Minnesota Street Gallery cancelled the premiere, they reached out about the possibility of reimagining the project so that it could be presented virtually on their website, and offered some additional funding en route to doing so. It occurred to me that not only could the project continue to move forward, albeit as a recording project rather than a performance project, but that it had the potential to be more successful this way. Since the players already had the click tracks and had been practicing along to them at home in preparation for the performance, I developed a concept that would allow for the players to record their parts directly from their own homes. I decided to break their parts up into “fragments” so that they wouldn’t have to record full takes of each movement. To do this, I snipped up each click track to the length of each predetermined fragment, and I added a “count-in” to each fragmented click track so the player could know when to enter; this was then reflected in their original part with new annotations.

To produce the recording, we loaned hi-fi recording equipment to each player on a week-by-week basis so that each player would keep the equipment for a week, and then it would be wiped down, sanitized, and delivered to the next player. After finishing a recording session on a given day, the player would then upload the recordings to an online cloud drive that I had access to, and I would review them in the evening and send comments for adjustments that should be made in the next day’s recording session. Once the player had recorded all of their fragments to satisfaction, they were finished and their contribution to the project was then complete.

Unfortunately, our pianist had traveled to Indiana in the interim period after the premiere was to take place but before beginning the recording sessions. However, she had brought her electric keyboard with her which she used to maintain her remote teaching schedule. It occurred to me that if I could get her to record her part in MIDI using her electric keyboard, I could then reproduce that MIDI recording on an acoustic Disklavier and record the Disklavier playback for the final mix. I shipped a small audio interface and some MIDI cables to Indiana, and the pianist was able to use that in conjunction with her keyboard and laptop’s built-in recording software to produce the MIDI recording. Being a faculty member at the University of California, Santa Cruz, I was able to access one of the university’s Disklaviers to capture the final recording of her part.

As we underwent this unique recording process, I noticed some interesting parallels with film/moviemaking (we were in fact working together with a video artist). In film acting compared to stage acting, an actor can make use of subtle facial expressions and slight changes in their tone of voice to convey the nuances of their part. In addition, most actors who contribute to a large film project only get a small glimpse of the full production; their scenes will be shot in an order achronological to the film itself, and they likely will not interact with most of the other actors in the film and will have little sense of the overall concept or tone of the film aside from what they can gather from the script. All of this was true of our recording process. By recording their parts independently and at home, the players could record their part in whatever order they pleased, and they could narrow their dynamic range by close-miking their instruments and allowing for subtle dynamic changes to provide the necessary contours. Similarly, aside from the fact that we held some preliminary rehearsals of the piece before shelter-in-place restrictions were put into effect, there was no need for the musicians to be acquainted with one another or to have worked together before. Another similarity that I alluded to earlier is that both of these mediums are created along a careful timeline that, once completed, is fixed and exists in real-time, allowing for intricate synchronicities that are not so easily achieved in live performance.

Some of the benefits that emerged out of working this way included the fact that since the players recorded their parts independently, those recordings were acoustically isolated from one another which offered advantages as to how they could be edited in post-production. Also, there was no need to coordinate and align the limited rental times of rehearsal space with the musicians already busy schedules, something that is difficult everywhere but can be an insurmountable task in the Bay Area. In essence, as technical complexities are added in the process of producing music this way, many logistical complexities, and the resources associated with them, are removed. These benefits notwithstanding, in order for musicians to work this way they need to accept the downsides which include the fact that they don’t get to play music “together;” more specifically, the social benefits of in-person music-making, both emotional and artistic, have been thrown aside and the cathartic culmination that comes during live performance has been lost. What has been gained, on the other hand, is the opportunity to produce idealized recordings that can make use of innovative compositional ideas that push past the limitations presented by in-person music-making.

Isotropes

I’d like to rewind back to mid-March of 2020. At that time, I had completed composing the music for Tides, learned that the premiere was to be cancelled, and developed some preliminary ideas for how to produce the remote-recording version of the piece without having yet done so (Tides was recorded in August). Realizing that I was well poised to make use of my skill set in composing with click tracks and eager to develop new and related compositional ideas, I was hungry to work on a new project. In a sleepless night, with infant yelps coming from the other room, I started to imagine the possibility of creating a modular open-instrumentation piece (think Terry Riley’s In C), in which a large group of musicians could record modules or “fragments” of their choosing. I imagined that a piece like this might be useful for lots of musicians, maybe even possible as an open-source project, as shelter-in-place orders were descending across the country and so many players were losing work. The next step was to find a group that was in need of such a project.

The U.C. Santa Cruz Wind Ensemble is an excellent group comprising students, community members, faculty members, and occasionally hired ringers, and happens to be directed by a close friend and collaborator of mine, Nat Berman. On March 15th, I texted Nat to ask him if he knew yet what the status of his ensemble was for the upcoming spring quarter, since it seemed likely at that moment that all of the university music ensembles would be cancelled. I myself am currently in my seventh year as the director of the Balinese gamelan ensembles at UCSC, and I was unsure then of the status of my own ensembles. Nat divined my underlying plan and responded to my text saying “Do you want to write us a click track piece that everyone can record individually?” As it turned out, both of my ensembles were indeed cancelled for that spring quarter, but this new project with Nat provided supplementary work for me while allowing for the wind ensemble to avoid cancellation.

The details of the commission were worked out in the following week after my initial text to Nat, and finalized around March 23. The piece would be called Isotropes, and the general concept was that it would be designed so that the players could record their parts remotely from home using whatever recording technology that was most readily available to them (generally cell phones and laptops, though various players had their own pro-audio recording gear that they used), and they would record along to click tracks that I would provide to accompany each part. The “premiere” would then be a virtual presentation of the final recording, mixing together all of the individual recordings made throughout the quarter. The first ensemble meeting was the very next week, on March 30, so I had about a week to compose some preliminary material for the piece and generate the parts and click tracks so that the musicians would have music to work on once the quarter started.

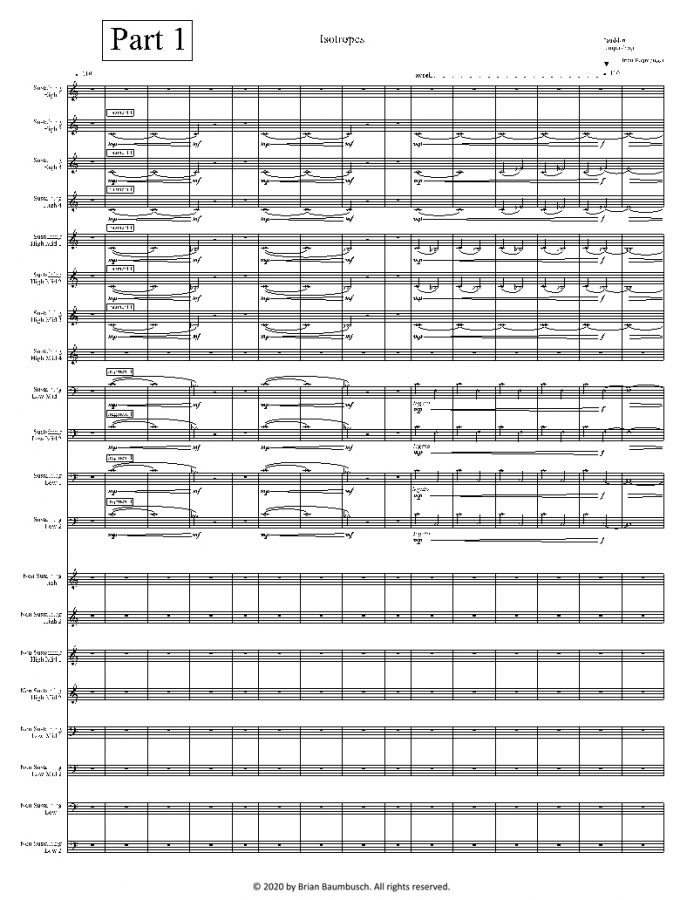

In that first week, as I further developed my concept for the piece and composed a collection of preliminary “fragments,” I continued to prioritize the need to create an open-instrumentation modular work. One of the reasons for this was that in the week before classes started, and even a week or two into the quarter, we were unsure of how many players would enroll in the ensemble and what the resulting instrumentation would be. Therefore, the piece needed to be flexible in regard to the number of players required and the instrumentation. As a result, I organized the score so that parts would be arranged first by instrument class (parts were either considered “sustaining” e.g. winds, strings, etc. or “non-sustaining” e.g. percussion, harp, piano, etc.) and then by register. In this way, the piece became “semi-open instrumentation” in that a given part must be played in the notated register and by an instrument in the same classification as the part, but within those restrictions the orchestration is flexible. Although this concept was tailored to some degree for the UCSC wind ensemble, the piece is designed to be for “adaptable orchestra” and playable by other types of orchestras such as string orchestras, symphony orchestras, etc.

Between March 23 and March 30, I wrote as much material as I could so as to keep the musicians busy once the quarter began and to give myself time to go back and write more of the piece as the musicians recorded the first section. Unlike most of the pieces that I compose in which I come up with a large formal structure for the entirety of the piece before composing various sections achronologically, in this case I composed from left to right, often feeling like I was composing one measure ahead of the musicians. And so it went for the ten weeks of the academic quarter: I would compose a movement of the piece, engrave the parts and click tracks and upload them onto a shared Google drive and as the musicians recorded each of the fragments from that movement, I would go back and compose the next movement. This happened in roughly two-week intervals so that over the course of about eight weeks, I had composed the four separate movements of the piece allowing for some final edits and re-records to take place during the final two weeks of the quarter.

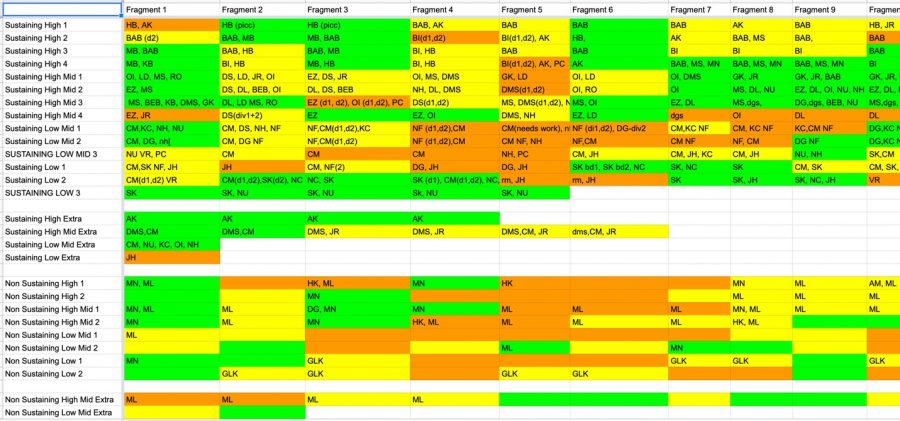

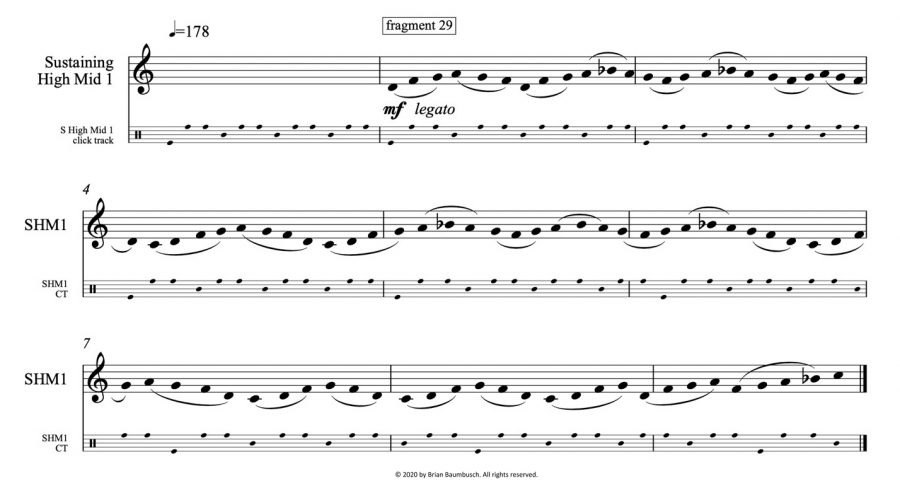

Similar to the concept that I described for the piece Tides, Isotropes is designed to be recorded in fragments wherein each part contains between 5 and 15 fragments per movement. There is a total of about 1000 fragments in the whole piece split between 22 parts. Each fragment has its own unique click track, and the fragments are also assigned a difficult level (easy, medium, or difficult). I transposed each fragment in all of the relevant keys so that the players could choose which fragments they wished to record (often based on the difficulty level) as long as that fragment was written for their instrument class and fell within their instrument’s register. To keep track of who recorded what, we created a giant spreadsheet containing a box for each fragment, color-coded green (easy), yellow (medium), and orange (difficult), where the players would mark their initials in the boxes representing the fragments that they planned to record.

The notated parts themselves referenced the accompanying click track, each of which contained a count-in and was composed of different pitched clicks to indicate the meter of the given fragment.

Rhythmically, the piece makes use of many instances of polytempo in which multiple simultaneously varying tempo streams occur between the parts. In these cases, the rhythmic notation that I chose to display for the various parts is simplified to only contain note-heads without stems, and those note-heads are roughly spatially oriented within the score. In looking at the part above, you can count 12 notes in the first measure and 8 notes in the last measure, which is evidence that this fragment is undergoing a gradual ritardando, even though that ritardando is not reflected in the global score but is only localized to this specific part. At this point in the piece, simultaneous with this part is another part that is undergoing a gradual accelerando; this occurs during the third movement in which these two discrete tempo streams begin with a relationship of 3/1 in that the faster tempo is three times as fast as the slower tempo, and over the course of about a minute they converge on one another.

This is just one of many instances of polytempo used in the piece. Other sections of the piece contain three or more simultaneous tempo streams, some of which may be changing while others remain static. Sometimes, the tempo will vary drastically between two adjacent fragments within a single part. From the perspective of the musicians, this is a non-issue because adjacent fragments are not recorded in a single take and might not even be recorded by the same player. The players’ perspective is always localized to the tempo of the fragment that they are recording at a given time, and the rhythmic complexity of the music only comes together as multiple recordings are mixed together in post-production.

In this way, Isotropes demonstrates some of the possibilities presented by the remote recording paradigm. Although it is a piece that could be performed live (while still using click-tracks), it is actually much easier to create through remote collaboration. It also justifies the use of technology, particularly click tracks, in composing and recording music. For me, the process of attempting to innovate musical time through my work with click tracks has often felt like more of a necessity than anything else. Once I decided that I was going to ask performers to use click tracks in live performance starting back in 2015, I had to justify that decision by creating music that couldn’t be made any other way. In the same way now, I hope that composers and ensembles who turn to click tracks for their remote collaborations can justify the use of that technology for reasons other than convenience or compromise.

Over the past 8 months, many ensembles have been forced to compromise their plans because of the limitations that they see resulting from the prohibition of in-person rehearsal and performance. Many have struggled as they’ve tried to adapt existing musical traditions to meet the current predicament, finding that much of these adaptations introduce difficulties and degradations to something that we are much better suited to do in person. Indeed, almost all of our music history has been predicated on our ability to manifest a group feeling of musical time, either through a unified pulse or as indicated by a conductor, while playing our instruments together in-person. This is something that we are very good at as a species and has been evidenced across the globe for millennia. However, this is not the only way to manifest musical time. As more and more musicians and ensembles are turning to recording technologies and click tracks to create music, we have a responsibility to use this technology to innovate music in ways that will expand our musical language even after a return to normalcy arrives. If for no other reason, we need to do this now because we CAN do this now. Right now is an incredible time to explore the possibilities of remote collaboration and innovative approaches to musical time, precisely because of the fact that so many musicians are at home and looking for work. In that way, the unprecedented time that we are in offers an unprecedented opportunity. We have no justification for blaming the current moment for curtailing our artistic potential. We need to start adopting new performance practices, rather than adapting or compromising existing ones.

[Ed. note: Other Minds has released a digital album of Brian Baumbusch’s music featuring both Isotropes and Tides which is available to download via Bandcamp as of December 18, 2020. – FJO]