Taking a Cue: Accompanying Early Film

Starting in 1908, film industry publications frequently included regular columns by cinema conductors, composers, and arrangers such as Samuel Berg, Ernst Luz, and Clarence Sinn. These articles offered suggestions—sometimes called “musical plots”—to cinema musicians on selecting and performing music for silent motion pictures. By the 1920s, cue sheets published by movie studios and independent publishers had become ornate, including cue titles, musical incipits, length of cue, and other information. The Silent Film Sound and Music Archive currently has 65 cue sheets available for free download and will be adding another 40 later this year.

While some film and film music historians think that these cue sheets were followed closely and that accompanists frequently purchased the music recommended in them, archival materials tell a different story. Cue sheets were often modified, used merely as the basis for ideas, or even ignored. This means that although we have an idea of what some accompanists might have played for individual films, we can’t know exactly what they played for individual screenings.

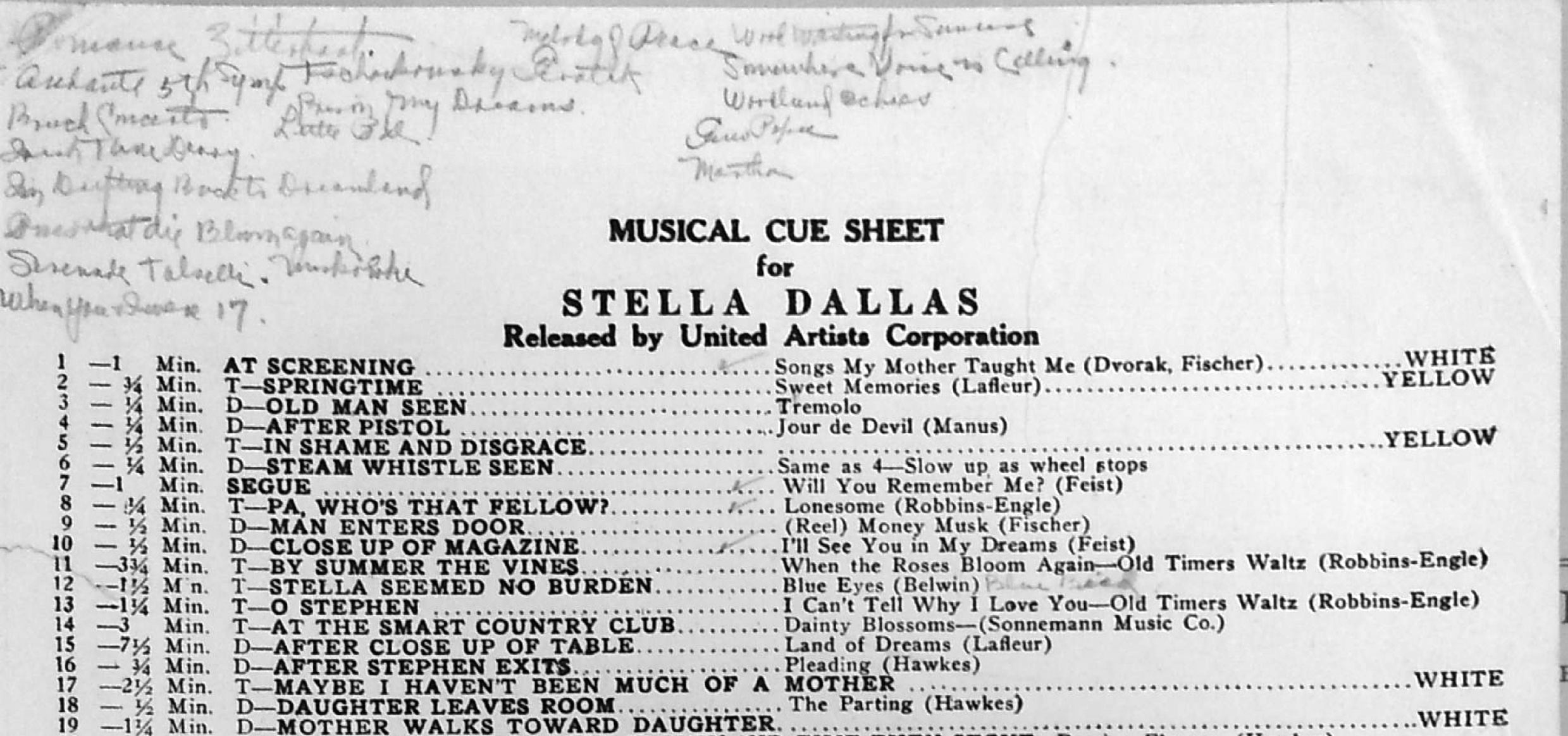

Many cue sheets in Silent Film Sound and Music Archive’s holdings show notations where the performer swapped out a suggested piece with one they already knew or owned. Claire Hamack, an accompanist whose scores, photoplay albums, and cue sheets are now online at SFSMA, often made changes to cue sheets—including adding her own original music.

For the 1925 film Stella Dallas, she made notes on the cue sheet of pieces she wanted to use in place of those recommended.

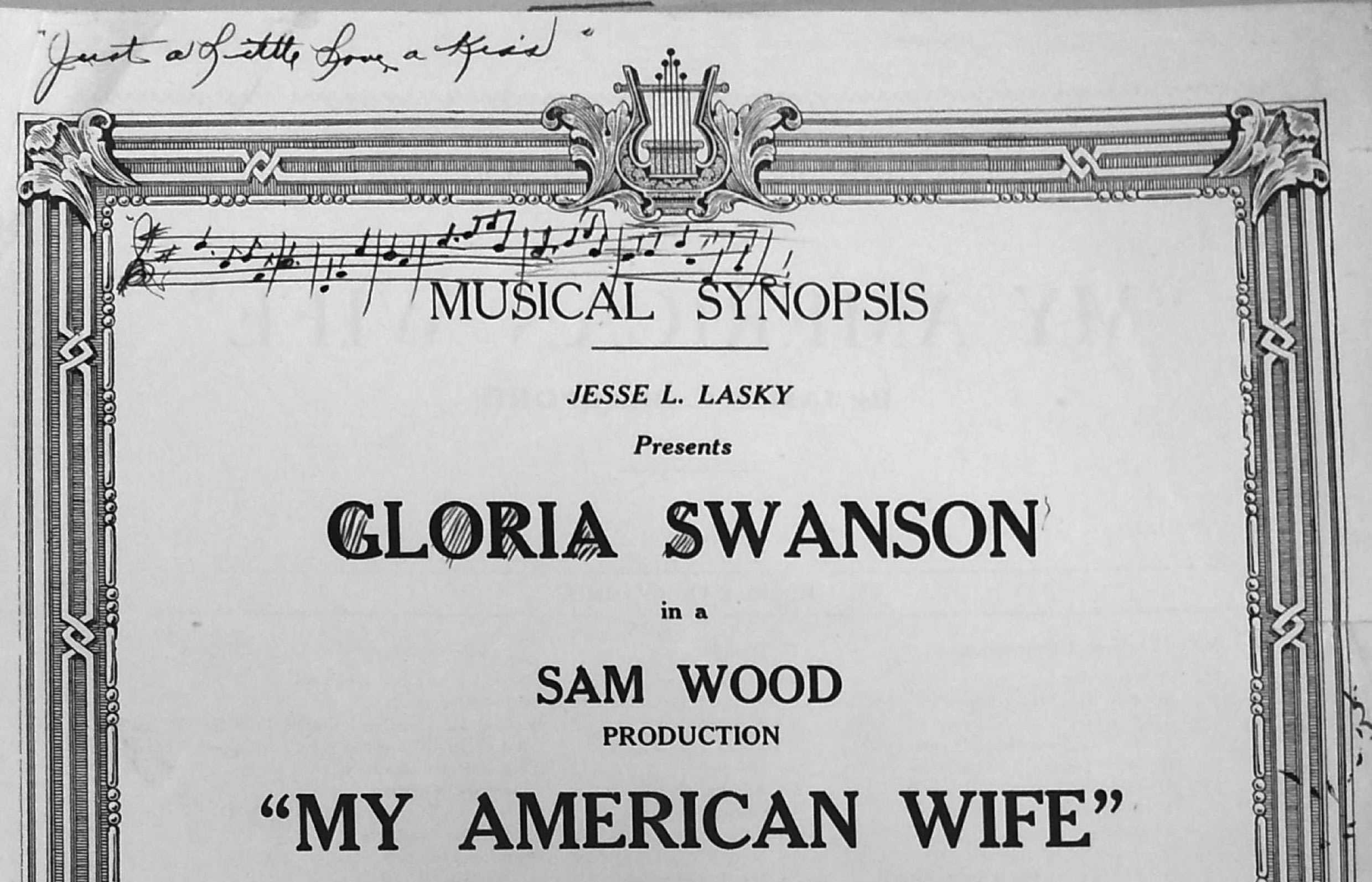

She also changed cues for the film When Knighthood was in Flower, a 1922 movie. Hamack replaced suggested themes by William F. Peters and Massenet with Franz Schubert’s “Moment Musical,” Edwin Lemare’s “Meditation,” and other selections. She specifically wrote over the printed titles for cue 5, “While Mary dreamed,” changing it from “Serenade Romantique” by Gaston Borch to “Wakey Little Bird,” and changing the music for cue 11, “It is near to midnight,” from “Romance—German (The Conqueror)” to Grieg’s “Dawn” from Peer Gynt. The cue sheet for The Dangerous Age, a 1927 German film directed by Eugen Illés, is covered with Hamack’s notes, including notation for an alternate, possibly original, theme, and indications that suggestions were replaced with other works (“In the Gloaming” is preferred over Otto Langey’s “Dream Shadows” for cue 23). Other cue sheets, including that for My American Wife (directed by Sam Wood, 1922), also bear short passages of handwritten notation for original themes and motifs. Hamack’s audiences would have heard Hamack’s musical interpretation of the film rather than that of the studio compiler.

One great find for SFSMA was a cue sheet created by cinema organist Hazel Burnett for the 1920 film Humoresque. Burnett had an incredible musical career, beginning by playing for live theater and small cinemas in the Midwest and working her way up to being a featured organist at the famed Aztec Theater in San Antonio. (More on Burnett here.) After her death, Burnett’s granddaughter Josephine gave all of her music and other materials to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The Burnett Collection contains a wide variety of resources, including printed cue sheets and full scores, photoplay albums, sheet music, and hundreds of pieces clipped out of The Etude and Melody magazines, which Burnett used as cues. Much of Burnett’s music is marked with performance indicia that confirm that she used it in accompanying silent film.

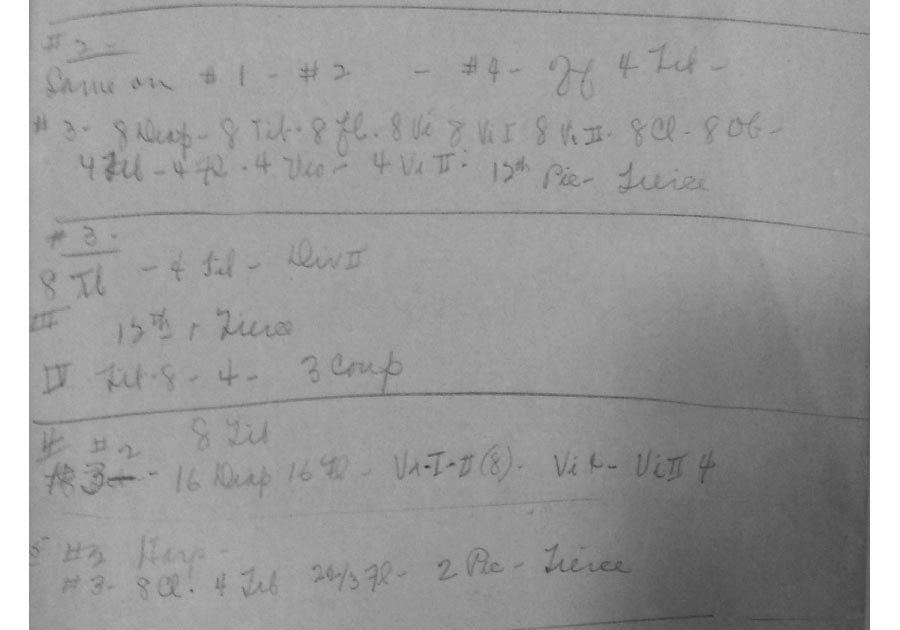

Numerous pieces of sheet music in her collection are labeled with cue numbers and descriptive notes: Frederick Vanderpool’s “The Want of You” was used for the cue “maw asleep” in one unidentified movie, and Edvard Grieg’s popular “Ase’s Death” accompanied another unknown film’s cue 27: “Mary prostrated.” “No. 5 Molto Agitato” from Breil’s Original Collection of Dramatic Music for Motion Picture Plays is marked as “14 phone rings”, while “No. 6 Andante Misterioso” was used for “[Cue] 2[:] man enters.” Burnett wrote the titles of accompaniment-appropriate pieces on the covers of the photoplay albums that contained the pieces, often including the page number for quick access. She also interleaved pieces of sheet music and pieces cut from Melody and The Etude between pages of her photoplay albums to create original modular scores. For some, it’s impossible to know what film the cues went with, but others are much clearer.

Cues for an unidentified film or films, Josephine Burnett Collection, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas—Austin

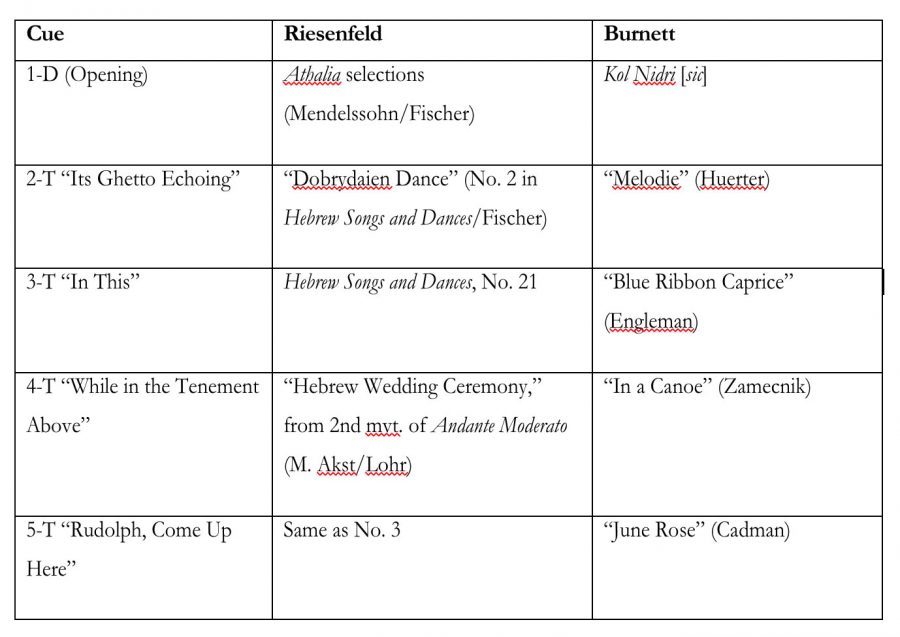

Humoresque is a classic melodrama about a young Jewish violinist. Celebrated film music composer and director Hugo Riesenfeld composed an original score for Humoresque for the film’s premiere, and it was this score that was most likely performed by a cinema orchestra and organist both at its premiere and on the road tour that followed, although Riesenfeld made slight changes to the score depending on where it was being shown. While Burnett almost certainly had access to Riesenfeld’s cue sheet, she compiled a rather different score from her own personal library. She kept two pieces Riesenfeld recommended: Dvorák’s “Humoresque,” which she could hardly avoid, and Bruch’s Kol Nidre. Here’s how her first five cues compare with Riesenfeld’s:

Note: ‘D’ refers to a direction cue or action; ‘T’ refers to the text of an intertitle. Punctuation modernized for clarity.

You can see Burnett’s full cue sheet for the film here. The Ransom Center is currently in the process of setting up a screening of Humoresque with live accompaniment using Burnett’s cues.

Having Burnett’s and Hamack’s cue sheets offers a glimpse of how these tools were used, adapted, or jettisoned by cinema musicians, and also conveys to us how score compilers interpreted scenes and assigned music to them. Would you or I think of recommending “Hail America” by Drumm as a piece for a Tudor-era picture (When Knighthood was in Flower)? Probably not, but prolific cue sheet author James C. Bradford did, and that alone tells us about scoring for early film and how aesthetics and approaches have changed since then. You can explore all of the cue sheets in the Archive by clicking on “Cue Sheets” under “Categories.”