New Music for a New Art Form: Photoplay Music

When we think of the music of the early 20th century, we might think of neoclassicism, Schoenberg, the English music renaissance, jazz, and maybe parlor song or vaudeville. But the advent of the moving picture brought about the development of an enormous amount of new music composed specifically to accompany film. While it’s true that some of the music used by film accompanists was borrowed from the vaudeville hall and stage melodramas, that some film accompanists improvised their scores, and that some film studios commissioned scores from composers for individual films, the majority of cinema musicians in the 1910s and 1920s relied heavily on a new genre, called photoplay music, for creating musical accompaniments to motion pictures of all lengths. Photoplay music consisted of short, evocative character pieces that could be easily strung together to create what is called a compiled score. Photoplay music was sold as individual sheet music titles and in albums or collections of eight to ten pieces, sometimes thematically linked, like Jacobs’ Piano Folio of Tone-Poems and Reveries and Jacobs’ Piano Folio of Oriental, Spanish, and Indian Music.

The Silent Film Sound and Music Archive (SFSMA) is, as its name suggests, a repository of music that was used to accompany films before the widespread use of synchronized records or sound-on-film technology. SFSMA, founded in 2014 to help performers and scholars find silent film music in one location, identifies and digitizes printed music and related materials and uploads them to the Archive, where they can be downloaded for free. Everything is posted under a Creative Commons ODC-By (Open Data Commons Attribution) License. SFSMA’s holdings include hundreds of pieces of photoplay music composed for the new art of the cinema. Although few of the composers of this repertoire are widely recognized today, they created music that helped establish a number of common tropes that still appear in film music. Composers including Helen Ware, Theodora Dutton (Blanche Ray Alden), Erno Rapée, William Axt, J. S. Zamecnik, and many others made a living composing short characteristic pieces for the cinema. All pieces appeared in a piano version, and most also had parts, as cinema ensembles could range from three players—often piano, violin or cello, and clarinet—to forty performers with full string and wind sections.

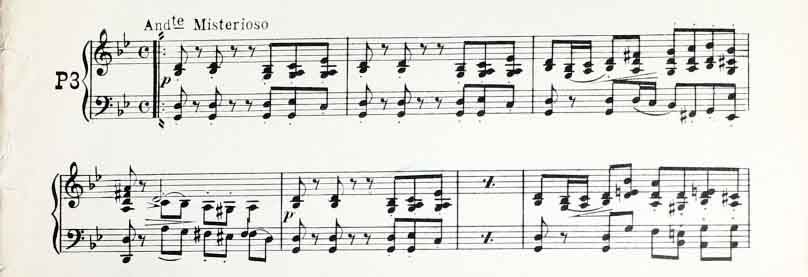

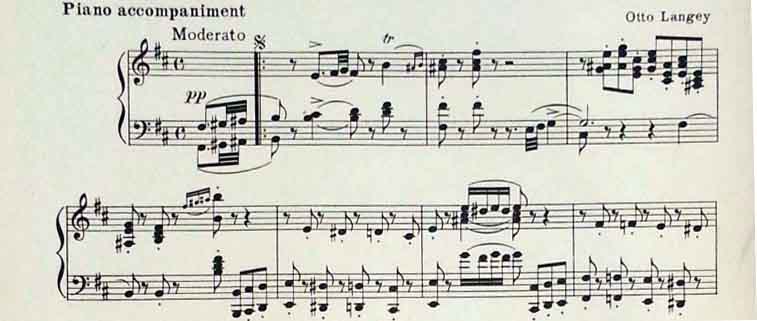

Composers were under great pressure to continually churn out generic pieces: cinema musicians didn’t want to use the same pieces week after week for different films. At the same time, it was important that photoplay pieces for the same general action or topic had similar characteristics so that accompanists could be consistent in their musical interpretations of films. Works for “hurry” or “gallop” were quick in tempo, mimicked the sound of hoof beats or heartbeats, and employed short note values, all of which suggested the associated speed of motion given in the title. SFSMA’s holdings include more than twenty individual “hurry” pieces, all suggesting speed and urgency. Similarly, “mysteriosos” or “misteriosos” were composed for scenes of stealth, burglary, the grotesque, the eerie, and the supernatural; there are more than thirty of these in the SFSMA database. All of the mysteriosos have things in common, including tempo and texture, but each one has a different primary melody and form, allowing for variety in accompanying.

Misterioso No. 1 (for horror, stealth, conspiracy, treachery) by Erno Rapee and William Axt (New York: Richmond-Robbins Inc., 1923), mm. 1-7.

Misterioso No. 1 (For Depicting Gruesome Scenes, Stealth, etc.) by Otto Langey (New York: G. Schirmer, 1915), mm. 1-7.

The works of Maurice Baron (who also published under the name Morris Aborn) provide a good introduction to the repertoire composed for moving pictures. Baron composed some pieces for specific films, such as his Shakespearean Sketches—Shakespeare adaptations were very popular in silent film, providing artistic gravitas to the medium—but most of his works were designed to be used as part of compiled scores. “Batifolage,” composed in 1926, was designated for “frolics, caprice,” and “Love’s Declaration” is intended to be used to accompany romances. Baron’s “Terror!” and “Suspicions” were intended for mysteries, horror, and domestic dramas. Baron also sought to capture the time in which he lived: “Radio Message (galop)” is meant to depict the urgency and speed of a Morse Code transmission, and “A Busy Thoroughfare” imitates the buggies, cars, trams, and people in an urban area.

“Radio Message” performed by Ethan Uslan (source).

The PianOrgan series, published by Belwin, collected Baron’s pieces into albums, making it easier for accompanists to select generic works by the composer. As Morris Aborn, Baron published western music for cowboy pictures; vice-related characters and events, such as drunk characters, opium dens, and speakeasies; music for battles; music for tragedies; and music for agitated scenes.

Excerpt from Maurice Baron’s “Prelude to a Western American Drama,” performed by the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra (source).

Excerpt from Maurice Baron’s “Valse Pathetique,” performed by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra (source).

Movie-watchers today might not know or think much about photoplay music, but over the last forty years, the showing of silent films with live accompaniment has experienced a renaissance. Ensembles such as the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra and the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra use photoplay music to create scores in the same manner accompanists would have in the 1910s or 1920s. Rod Sauer, director of the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, researches what music might have been used at showings of the films they accompany, but often selects different pieces that the group feels better convey the action and intent of the film. In creating a compiled score for the film Beggars of Life, for example, Sauer found that some of the music suggested for use with the film had racist connotations, such as using an upbeat cakewalk piece to accompany a scene in which a black character experiences tragedy, so he chose other photoplay pieces for the score. Educators are also using photoplay music: instructors teaching film music, film history, and popular music history have used pieces from SFSMA to demonstrate how a compiled score might be created, and students are scoring short films—both old and new—using music from the Archive.

You can find photoplay music in SFSMA in a variety of ways. If you’re interested in particular composers, you can search by their names. You can also search by “mood,” a silent-era designation that categorized music by scenario. Need a sad piece? A search on “tragic” brings up twelve pieces with “tragic” in the title or mood subtitle. Want to see a collection of similar pieces? Search “album” to find all of the collections in the archive. You can also search by clicking on “sheet music” in the Categories section, and then refining your search by mood, instrumentation, or other factor. To hear recordings of photoplay pieces in a variety of moods, click on “Video and Audio” under Categories to pull up a list of recordings made by silent film accompanist Ethan Uslan. There are hundreds of pieces in the Archive to discover and use for accompaniment or analysis, all of it once an influential force on the development of the cinematic score.