Bun-Ching Lam: Home is Where You Park Your Suitcase

Video presentations and photography by Molly Sheridan

Transcription by Julia Lu

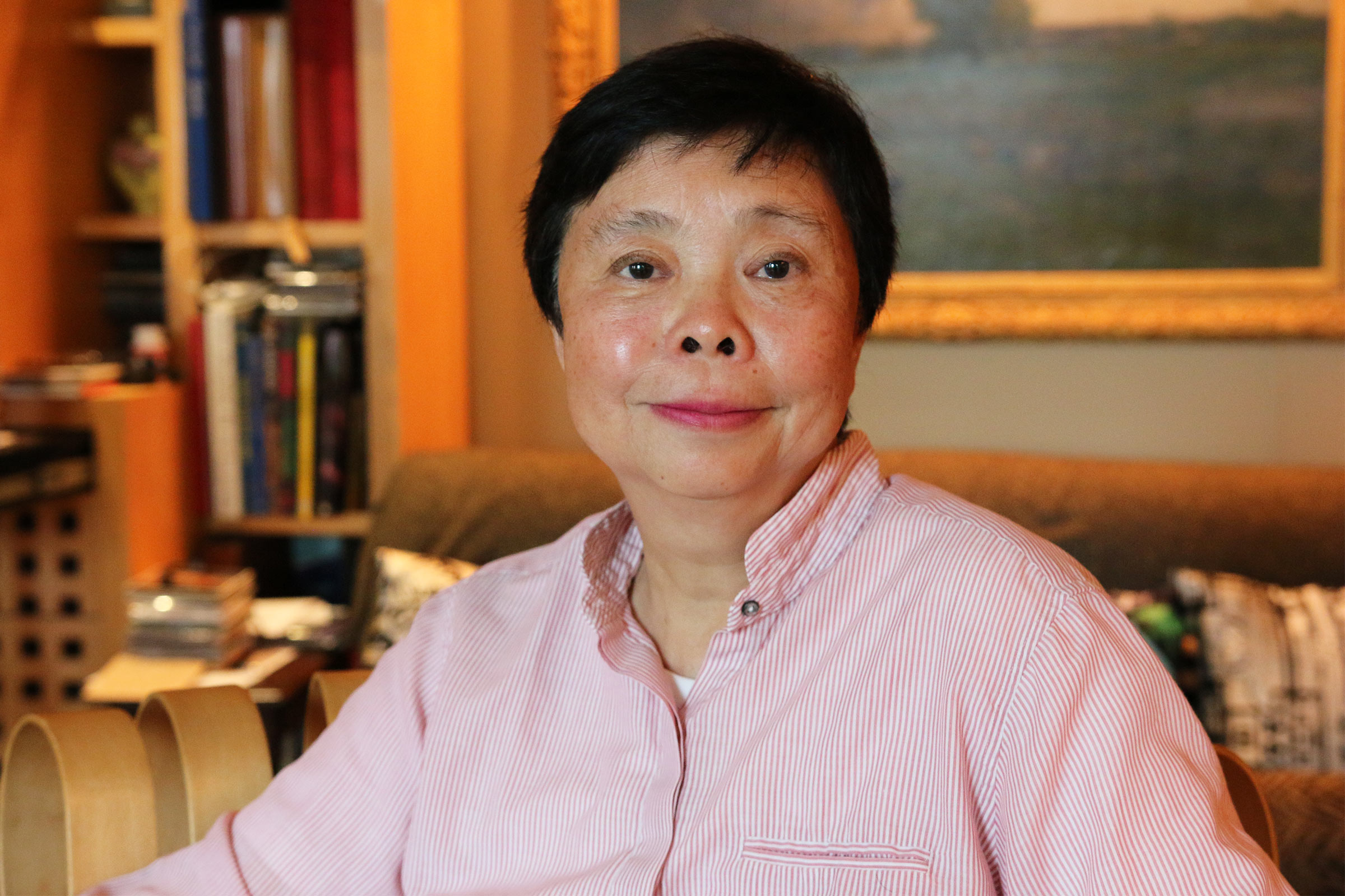

Born in Macau, educated in Hong Kong and California, and now dividing her time between Paris and upstate New York, Bun-Ching Lam has created a fascinating body of music that is shaped by her multicultural life experiences as well as her sensitivity to a wide range of instrumental sonorities and extreme curiosity.

“I’m always curious, and I try anything at least once,” she told us when we visited her at the home of baritone Thomas Buckner, with whom she had been rehearsing in preparation for the New York premiere of her recent song cycle Conversation with My Soul, based on texts by Lebanese-American poet and painter Etel Adnan. (The performance, with the Tana Quartet, will take place at Roulette on November 16 as part of Buckner’s Interpretations series, celebrating its 30th anniversary this season.)

Macau, she acknowledged, was a challenging place for an aspiring concert music composer since, when she was growing up, live performances of classical music were extremely rare. But thanks to her father and some friends who owned classical music recordings, she was able to learn about the repertoire. At the same time, she immersed herself in many other kinds of music, from traditional Cantonese folksongs to the local jazz of Dr. Pedro Lobo to discovering the Beatles on the radio. And she learned how to play many different musical instruments, from the Chinese yangqin to the baritone horn (which she played in a school band) to the accordion. But soon her primary focus was playing the piano, although she admitted that she preferred improvising to practicing: “Maybe that’s the beginning of my composition.” Still, she enrolled as a piano major at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Lam’s composing activities did not officially begin until she came to the United States as an exchange student. She spent a year at the University of Redlands in California, where she was exposed to a wide range of experimental approaches under the tutelage of Barney Childs. But after she returned to Hong Kong, she won an art song composition competition, which helped pay off her debts and momentarily led her to think that composing was lucrative. When she decided to pursue a graduate degree, she enrolled at the University of California, San Diego, and wound up studying composition with Bernard Rands, Roger Reynolds, and Pauline Oliveros. Unlike her peers, she did not come in with a huge portfolio of works, but within only a few years, Lam began creating music in a distinct, personal style. One of her early works from this time—Bittersweet Music I for solo piccolo—remains one of her most frequently played compositions.

“One of the things that I already had was an idea about what I think music is,” she remembered. “And I haven’t really changed style. I’m always old fashioned because I like melodies. Even now, writing melodies is not fashionable. I’ve never been with any fashion. I’m always out of fashion. When you’re always out of fashion, you’re always in fashion because fashion is a very stupid thing. … I don’t want to be Mahler. You cannot be Mahler. I don’t want to be Respighi, either. I want to be me.”

Being Bun-Ching Lam means creating music slowly and carefully. She rarely composes more than one work per year. And although she claims that with each piece she’s “starting from scratch,” every gesture is meticulously shaped, with an end result that blurs different aesthetics seamlessly. She frequently juxtaposes instruments as well as texts from East Asia and the West, as well as from the Middle East.

“It’s all available,” she explained. “Just like nowadays, you don’t just eat Chinese food. You eat Thai, Afghani, what have you, because everything is available, so why not use it?”

A conversation with Bun-Ching Lam at the home of Thomas Buckner in New York City

October 8, 2018—12:30 p.m.

Video presentation by Molly Sheridan

Frank J. Oteri: I’ve wanted to talk to you for years, but now seems a particularly apt time since the world is currently going through a very strange period of resurgent nationalism and xenophobia. More than most composers I can think of, you are so polynational, both in terms of your life and your music, to the point that I don’t think what you do could have existed if you did not have this range of experience in so many different places.

Bun-Ching Lam: Absolutely. I agree with you. Because I’ve lived in all these places, I’m familiar with so many different cultures. I speak five languages. None of them well, of course. But yes, I have a different perspective than someone who has been stationed in one place and stayed there forever.

FJO: You were born and raised in Macau, which is a very unusual place already. It, in itself, is a multicultural oasis. When you were growing up, it was still ruled by Portugal.

BCL: Yes, until 1999. My piano teacher was Macanese, so our lessons consisted of Cantonese and English, because I don’t speak Portuguese but she’s speaks very good Cantonese. And then from her, I also learned a lot of English.

FJO: So Portuguese is not one of your five languages.

BCL: No, at that time, we had resistance about learning the colonist language. But I should have learned Portuguese, because then I could read Pessoa in Portuguese.

FJO: The majority of the population of Macau is Cantonese-speaking Chinese, but the colonial rulers were Portuguese. These are two very different cultures. But because both the Chinese and the Portuguese there were separated from their motherlands, in some ways they both developed their own cultures.

BC: The Portuguese who were there they called Macanese. They don’t really speak the same Portuguese as the people in Portugal; the language has changed. They have their own subculture and their own patois that the Portuguese don’t know. And they have poets. Actually I have a piece where I have used that particular language called Macau Cantata. It uses all the different languages that have passed through Macau. The famous Chinese poet and playwright Tang Xianzu was in Macau. We all know his Peony Pavilion. He has this description of Macau as the first place where East and West meet. And then [Matteo] Ricci; he went to China and he was stationed in Macau, because that was the only place that you could get access to the mainland. It’s a fascinating place. In comparison to Hong Kong, Macau actually has its own genuine culture that is very different from any other place. Of course Hong Kong also has its local culture, but it’s very different. And, even now, you can go from one place to the other with no problem.

[banneradvert]

FJO: So I’m curious about how you first got exposed to music growing up in Macau. Before you started studying piano, what were you listening to? I have this strangely packaged CD that I got years ago that’s a collection of music from Macau that has a recording of your Saudades de Macau on it. But it also includes piano music by Father Aureo Castro and dance music by Pedro Lobo.

BCL: Pedro Lobo! We called him Dr. Lobo. Every day at 12 o’clock, the radio program had his band on, which played a kind of jazz music. They also had a lot of pop musicians from the ‘50s. And Father Aureo—actually I was just in Macau not too long ago and it was the 55th anniversary of the music school he founded, so they had all kinds of activities and also played his music. I was invited to do a lecture for the little kids. It was a lot of fun.

So I heard all that, and I also heard Cantonese music and The Beatles. Everything. I loved rock music. But actually listening to classical music was difficult, because there would be one concert a year of classical music. I had friends, so we borrowed records. And my father loved music and had records of classical music. The first concert I heard was Jean-Pierre Rampal playing the flute. I didn’t hear any real live orchestral music until I was 16, when I went to Hong Kong for the first time.

FJO: How much traditional Chinese music were you exposed to in Macau?

BCL: Oh, there were all kinds of things. And I also played a little on Chinese instruments. I played the yangqin and the moon-shaped lute, but never very well. Then I played in the school band. I started out as a conductor, and then I learned to play baritone horn, because nobody wanted to play it, so I played it. And I learned to play accordion in one day; I had to go on stage the next day. So that was a lot of fun.

FJO: So you were playing wind band music?

BCL: Yeah, and we had our own transcriptions. I actually arranged certain things. I was 14 or 15. That was interesting because I got to learn various instruments. I know how to play “Home, Sweet Home” on any instrument, but not very well.

FJO: There have been at least two other composers with international reputations besides you who are from Macau. A lot of people probably don’t realize that Xian Xinghai was born in Macau, even though he became a very iconic composer in mainland China because of his role in the revolution and his Yellow River Cantata was turned into a piano concerto during the Cultural Revolution. It’s still played all the time.

BCL: He died very young.

FJO: And then there’s Doming Lam, who I think is a very interesting composer.

BCL: Absolutely, but he basically lives in Hong Kong. Then he went to Canada for a while. He never really lived in Macau.

FJO: I think in order to establish a career for himself, he had to leave Macau and go somewhere that had a larger musical scene.

BCL: Macau is a very, very small place. And it’s very hard to stay there forever.

FJO: So you left Macau to study piano in Hong Kong. But at that point, you still were not thinking of writing music.

BCL: No. I wrote some little songs, and one time I sent one to a magazine but I never heard from them. Since I don’t like to practice piano, I improvised. I didn’t have a piano at home, so I practiced piano at school, right down in the hallway, and people would come and pass by. My father wanted to make sure that I practiced, so he had a teacher [check in on me] and he had a little book. Each time after I finished practicing he would say, “Very good” or “It doesn’t seem to be very good today.” But since he didn’t know anything about music, I’d just play some things, I just improvised; I never practiced. Maybe that’s the beginning of my composition.

FJO: So many different biographies of you state that you didn’t actually start writing music until you arrived in the United States.

BCL: Right.

FJO: So I thought, even though you were born and raised in Macau and you studied in Hong Kong and eventually started spending a great deal of your time in France, since you started writing music here, if anyone feels the need to make any kind of nationalistic claims about your identity as a composer, a strong case could be made that you’re an American composer.

BCL: I could be. I don’t know who I am. Sometimes in one of those ISCM things, they will say I’m a Portuguese composer.

FJO: Really?

BCL: Because I was born and raised in Macau. I don’t know what composer I am. I’m just me.

FJO: But your serious exposure to contemporary music happened in Hong Kong. I know that you met Richard Tsang when you were there.

BCL: Well, we were in the same class. We were buddies. He started to write music first, and I was just a piano player. The first time I had contact with contemporary music was when I was in the fourth year. My piano teacher said, “You should play Schoenberg.” I actually found it quite ugly. I was doing Opus 11.

In my second year, I went to University of Redlands as an exchange student. I was there only for one year and then I went back to Hong Kong to finish my degree there. But I wanted to learn about contemporary music, so I was playing in the new music ensemble and we were doing Cage and Barney Childs—he was the teacher. And I learned electronic music. I just wanted to be exposed to different things. One time, we did this John Cage thing and different music happened at the same time. I said, “This is fun.” That was actually in my first composition course. I studied with Barney, and I wrote a piece called Theme and Variations on a Chinese Folksong. That was my first composition. In each variation, the style changes. Some of it sounds like Hindemith, but it sort of progressively gets more away from the tonal. It [uses] a simple tune [sings melody]. I don’t even know what the name is, but I always liked that tune.

FJO: Do you still have a manuscript of it somewhere?

BCL: I don’t think so.

FJO: Maybe it’ll turn up somewhere.

BCL: In the Yale Library. Everything turns up there.

FJO: Or at the Sacher Foundation.

BCL: I doubt it very much.

FJO: So with so many places that have been part of your life, do you consider any place to be home?

BCL: Well, I think home is where you park your suitcase. Your root is somewhere else. But if I carry my root with me, it’s just dangling. It never goes anywhere; it’s just where I am. Nowadays people always say the DNA. The DNA’s there. So it doesn’t matter where I live. The Chinese say, “When the leaves fall off, it goes back to the root.” Maybe one of these days I will want to go back to live in Macau, because it’s true, each time I go back there, there’s a certain kind of familiarity. Or if I go to China. Deep down, I’m certainly Chinese. Therefore, to answer your question, I’m a Chinese composer. I always say, “You’re once Chinese, you’ll always be Chinese.” That’s how I think. Somehow it’s because of how I was brought up. Certain kinds of Confucian thinking are ingrained in me, even though I like Chuang Zhu and Lao Tzu much better; that part of the philosophical outlook on life is ingrained.

FJO: Well, if there’s anything that more pieces of yours have in common than anything else, it’s an association with Macau. And even in the last ten years, you’ve written three works that reference Macau. Aside from the Macau Cantata, which you mentioned, there’s also Five Views of Macau and Scenes from Old Macau.

BCL: Definitely I like Macau, but there’s also a practical reason. I was a composer-in-residence in Macau. They wanted me to write Macau this, Macau that. So I think of myself like the Respighi of Macau. I’m actually tired of it, so I’m no longer composer-in-residence. Still, the next piece I’m working on is for the Macau Youth Orchestra. It’s more interesting to see how I can relate to the young people.

FJO: To get back to your formative years, I’m curious about what happened next after you wrote that first piece of music when you were studying with Barney Childs. You went back to Hong Kong, but you obviously got the composing bug since not long after that you came back here to pursue a graduate degree in composition.

BCL: I had borrowed some money from the school and I was totally broke. Then the last year there was a composition competition for songs and the prize was pretty high. Richard Tsang was also applying for it, so I thought maybe I should write a song. Then if I win, I guess I can pay back my loan. That’s how I started. It was a very short song. I hid in the practice room and I was looking at all the French chansons. I found some harmonies and I made this song up. Then I entered and I won. So I said, that’s great. It’s very lucrative being a composer.

FJO: That’s very different from most people’s experiences.

BCL: Well, that was the only time that I really won some money. I’m still waiting for my MacArthur, but I’m not holding my breath.

FJO: Yeah, they just announced this year’s winners, so maybe next year.

BCL: Right, it’s great. Fantastic.

FJO: But okay, you won this competition and you paid back the loan.

BCL: And I went to America.

FJO: In order to pursue a degree in composition?

BCL: No. I went to UC San Diego for a master’s and at that time they had a track system where you had to do different things. I picked piano of course, because I applied as a pianist, and then they had theoretical study, and then there was some sort of extended technique. But since I don’t like history because I don’t remember anything, I said, “Okay, I’ll try composition.” At first, I was at the undergraduate composition seminar and Bernard Rands was the teacher. So I wrote a piece for solo flute. That was the assignment. Everybody had to write a piece for solo flute. And then the next assignment was a duet. You add another line on top of that piece, so it would be a duet for two flutes. I said, “Wow, by the time I’m 70, I will be writing a symphony.” But then in the second quarter, I got promoted into the graduate seminar. But I really didn’t have a portfolio. All the people already were composing since they were born. I was just a beginner.

FJO: You were a beginner, but you were already studying with Bernard Rands.

BCL: Well, he was employed to teach there, so he had to teach anybody.

FJO: But you ultimately wound up studying composition with a lot of other very interesting people as well. We’ve actually done talks with quite a few of the people you studied with—Bernard Rands, Roger Reynolds, and Pauline Oliveros. They are so different from each other.

BCL: Exactly. And there was another person I studied with, Robert Erickson, who was totally different [from all of them]. I was in all of their seminars. For me, it was fantastic that I got to learn from different people.

FJO: And what’s fascinating is, although you came in without a portfolio of compositions in the beginning, within five years you were writing pieces that clearly have a distinct compositional identity, and which are still receiving performances, like the piccolo solo Bittersweet Music from 1981. Of course, it helps that there isn’t a lot of solo piccolo repertoire.

BCL: That’s right. That’s why I pick those weird things to do.

FJO: It’s a good idea to write a piece that can have that kind of circulation. But still, it seems really unusual to me that you were able to create something that is so fully formed so soon after starting to write music.

BCL: I don’t know. I have no idea. I think that one of the things that I already had was an idea about what I think music is. And I haven’t really changed style. I’m always old fashioned because I like melodies. Even now, writing melodies is not fashionable. I’ve never been with any fashion. I’m always out of fashion. When you’re always out of fashion, you’re always in fashion because fashion is a very stupid thing. Can you imagine now everybody is wearing bell bottom pants. That was in the 1960s. So now you have to get rid of all your skinny pants? Why would you want to do that? The only people who make money are the people who manufacture it!

Music is the same thing. It was fashionable to write 12-tone music. Now nobody writes 12-tone music except a few people in California, which used to be anti-12-tone music. And now it’s all environmental—the cosmos and all those things. Once it was fashionable to be Chinese, like 10 or 20 years ago. Now it’s fashionable to be Finnish or some other up-north people like Iceland, which is fantastic because everybody has something to offer. So I like it. I think it’s a great time. People are open to different things. But when you’re open to different things, other things get shut off.

FJO: So, would it be a fair assessment to say that you primarily compose by intuition, or is there some sort of secret system behind the pieces you’ve written? What causes a piece to get formed the way it does?

BCL: I don’t know. It’s getting progressively more difficult for me to write. I’m writing a short piece now. I love strange combinations, and this piece is for shakuhachi, recorder, an oud, a theorbo, and a kugo, which is a harp. And I’m just racking my brain about how to make it work. With each piece I’m just starting from scratch. When it happens, it happens. That’s why it takes me a long time to write a piece, because I don’t know what I’m doing.

FJO: So would you say you come up with the idea of what the combination of the instruments is first, and then it leads you in a certain direction?

BCL: Yes, but that happened to be the group that commissioned it. There’s no repertoire; you just have to make it up.

FJO: Interesting. One of the things I find so fascinating about your work is how it embraces so many different cultural traditions. You’re Chinese and you’ve written a lot of works that involve Chinese instruments, as well as Chinese instruments in combination with Western instruments. But you’ve also written works for Japanese instruments. You mentioned this new piece has shakuhachi. Plus you’ve written for gamelan, which is Indonesian, and for Middle Eastern instruments. The entire world’s sounds are fair game.

BCL: I think so. It’s all available. Just like nowadays, you don’t just eat Chinese food. You eat Thai, Afghani, what have you, because everything is available, so why not use it? I’m always curious, and I try anything at least once.

FJO: Yet at the same time, and I guess this strikes to the whole notion of fashion, there’s a huge movement nowadays where people believe if you’re not from a culture, you can’t really understand that culture and what the larger meanings of things are from that culture, and therefore you shouldn’t be appropriating them.

BCL: Right. That’s a big discussion. Like if you’re not black, you shouldn’t write about black culture. I don’t know. I have no answer. I’m not stealing; I’m just borrowing. And I’m not appropriating, because if I’m writing for shakuhachi, I’m not trying to be Japanese, or if I write for string quartet, I’m not pretending to be European. So I don’t see any reason not to do it. But you have to do it with respect. If as an American, you just write music that sounds like gamelan music and there is nothing really different, then maybe that could be a question. I could be wrong.

FJO: One thing that’s so interesting about your approach is the ways things blur together. By combining these different sound worlds, the result is music that would not have been possible from any of those places in isolation. I was listening again this morning to your song cycle Nachtgesänge, which is based on poetry by Friedrich Hölderlin. You use such an unusual combination of instruments. You included a koto, which is Japanese, and also a saxophone, which though of European origin really came into its own in the USA. Hölderlin has been described as the most German of German poets, but you set his poetry using sonorities from all over the world. And in doing that, his poetry becomes—

BCL: —something else. Yeah. But I didn’t choose the instrumentation. It was for the CrossSound Festival in Alaska. They have those players and so I chose that, but I have to find a rationale for how to combine these instruments, not only because of sound. I live with a German so that makes it work, I think. But actually the thinking is quite Chinese, because of the classification of the instruments by material. I was thinking there’s wood, there’s brass, there’s metal, and then there’s something that’s neutral to combine them all together. And the reason is because Hölderlin is a fantastic poet. I also made a book with that text with some of my etchings. I learned about Hölderlin and this whole German Romantic world—how they expressed words was just fantastic, just the sounds of them. I just love it.

FJO: So German must be one of your five languages then.

BCL: Yes. I understand almost everything, but when I speak everybody laughs because I just don’t say things the same way. But it’s grammatically correct, usually.

FJO: If the unusual instrumental combinations you write for are the result of the people who are commissioning a work from you, you obviously don’t have a lot of say in that. But what if there was a combination that you felt wouldn’t work for your music?

BCL: Then I just don’t accept the commission.

FJO: So there have been times you’ve turned down commissions.

BCL: Yes, since I write slowly, sometimes I just have to say, “Sorry, I can’t do that.” I still haven’t written a woodwind quintet. It would be kind of fun to do, but that’s also very difficult because you right away think about these bad woodwind quintets that have been written.

FJO: But the text is something that you usually choose, I imagine, although I know that you wrote a setting of Heinrich Heine for Tom Buckner, whose home we’re in now, because it was something that he wanted, so you chose that text as a gift to him.

BCL: Everybody loves Heine. It was a love song. It was a present for Kamala and Tom for their wedding anniversary. But I usually choose the text. I’ve written some Dada songs [with texts] by Hugh Ball. I just love that silly nonsense; you can make anything out of it. That was written in 1985, before any big commissions.

FJO: You are interested in so many things, so you probably read more texts than the ones you wind up setting. What makes a text cry out to you and make you want to set it to music?

BCL: Well, I don’t read too terribly much, because I really don’t have that much time. I’ll just see something. But it has to speak to me somehow; I have to see an image. For instance, I’m learning French, so I’m paying more attention to French poets. I also still use a lot of Chinese poems.

FJO: But the thing that I find so fascinating, to take it back again to that Hölderlin setting, is the text that you choose doesn’t necessarily determine the kind of musical sound world that that text is in. The idea that a Japanese instrument could be used to bring out the words of Hölderlin is quite interesting. I know that you have done some settings of Chinese poetry using Chinese instruments, but then you’ve also done Chinese settings that don’t use any Chinese instruments at all.

BCL: Right. I think the texts I do something with are very universal. Mostly they are poems about love or about isolation. Human emotion is common to every culture and every language. Therefore music is a great way to illuminate those feelings and those emotions. For instance, there’s one piece at the concert on November 16, which is the 30th anniversary for the Interpretation Series, called Conversation with My Soul; [the text is] by the great poet, painter, and philosopher Etel Adnan. I wanted to write a piece for Tom and she’s Tom’s close friend; that’s a present for her 91st birthday that Tom did for her. I wanted to write another string quartet, but I thought it might be easier to add a baritone voice to it and, for me, it was to discover the meaning of her language. Sometimes it’s very obscure, because she’s Lebanese and English is her second language, just like me, so her use of language is very different from people like John Ashbery. And the syntax—sometimes you don’t know where you are! Just like music, it’s ambiguous; you don’t know exactly what the meaning is.

FJO: So have you ever set a text in a language that you don’t speak to some extent?

BCL: I try not to. It would be difficult to set something in Greek, because it’s like Greek to me.

FJO: Curiously, one of my favorite pieces of yours is one from very early on, your solo percussion piece Lue.

BCL: Wow, I didn’t know that you knew my music so well. That makes me feel happy.

FJO: Well, I thought it would be interesting to talk about since we’re talking about understanding different languages. To me that piece sounds so idiomatic for percussion, but back in 1983, when you wrote it, I can’t imagine that you would have had a ton of background with percussion instruments.

BCL: Well, I do hit the table with the chopsticks, once in a while. I don’t know. You just imagine. You don’t have to draw a picture; you just know you have to reach from here to there in this time. That was a very extravagant piece. That piece is not played very much because it costs a lot of money to rent the instruments. But I was at Cornish, and my wonderful colleagues helped me and somehow it all worked.

FJO: It’s interesting that it doesn’t get performed much because it’s one of the only pieces of yours that there are two different commercial recordings of.

BCL: Is that right?

FJO: There’s the first recording that was released on CRI decades ago and then a more recent one on Mutable.

BCL: Right. Well, it’s too expensive. Nobody plays that. They don’t want to move those things anymore. There have been other performances in New Jersey because of a percussion teacher there.

FJO: Raymond DesRoches.

BCL: He’s great.

FJO: You wrote a second percussion piece later on called Klang, which I’ve never heard and would love to hear.

BCL: There was a commercial recording of it in Europe, but I don’t know how commercial it is, with a great percussionist, Fritz Hauser, a Swiss guy. He just did a big festival in Lucerne and he commissioned that piece. The great thing is that he always had two bass drums. I love kung fu books [even though] I don’t read too many of them; [in kung fu] human beings have a way to separate the body. You can have your left trying to control your right, so you try to separate yourself. So that piece [Klang] is very difficult to play because he has to do all these things. So I had fun doing that piece, but very few people play that piece also. I think he was the only person who played it.

FJO: I suppose that’s the opposite of the piece you wrote for piccolo, Bittersweet Music, which many people have performed.

BCL: Yeah. Maybe. It’s short. And it’s bittersweet, more sweet than bitter.

FJO: You’ve written three pieces with that title. The third one is for bass flute, which is a lot less common.

BCL: Yeah, a lot of people don’t have bass flute, so I don’t think that piece has been played very much.

FJO: There is at least one video of it online which is really nice. Another piece that I wanted to talk with you a bit about is …Like Water, which has also been recorded twice. It’s a trio of Western instruments—violin, piano, and percussion—but once again, it’s such a seamless blur of East and West, Asian, European, and American traditions. If I didn’t know it was your music, I’d be hard-pressed to figure out where this music came from; I’d have no idea.

BCL: Oh, that’s great. Thank you. I’m from Mars!

FJO: Though it’s seamless, from minute to minute it goes through so many different stylistic sound worlds, so I’m wondering what your roadmap for that piece was.

BCL: Well, that piece was written for dance. It was a collaboration with the choreographer June Watanabe. The problem with dance music is that you write something and then it’s too short or too long. You can’t just add a couple of minutes here or there, except Stravinsky who just adds more repeats! She wanted a piece that had something to do with water. So I just wrote pieces for her. Each day, I wrote one, more or less. I’d just get up in the morning and say, “Okay, today I’ll write one.” Then one after the other, because I had a deadline. That helps too, once in a while. Instead of just dreaming about a piece, you actually have to work on it and finish it. So that’s how it all came about. And then it was for The Abel-Steinberg-Winant Trio, and they are wonderful musicians; they can play anything.

FJO: You’ve mostly written pieces for smaller ensembles, but I wanted to talk with you a bit about the orchestra, because you have written several orchestra pieces and have also conducted them. Earlier in this conversation you were talking about writing a piece when you studied with Bernard Rands that started as a solo and then became a duo, and you imagined that it would eventually become a symphony.

BCL: Well, I still haven’t written a symphony, so I’m still waiting.

FJO: Do you want to?

BCL: I don’t know. It’s too difficult to write a symphony.

FJO: You’ve written concertos, though.

BCL: Yeah.

FJO: Including two pipa concertos.

BCL: Actually both of them will be performed in Germany at the end of this month, which is very rare.

FJO: Together on the same concert?

BCL: Yes.

FJO: Wow.

BCL: They’re going to do it three times. So this is a great treat for me.

FJO: That’s fantastic. So are there a lot of performances of your music in Europe?

BCL: No, not really. Once in a while.

FJO: Does it help to be based there a good deal of the time?

BCL: I don’t think so.

FJO: So then what led you to spend so much of your time in Paris?

BCL: The food is better!

FJO: There’s some pretty good food in New York, too.

BCL: It’s true, but I don’t live in New York anymore. I’m kidding, but in terms of ingredients, it’s still better [in Paris]. But that’s not really the main thing; it’s the culture. Since I left New York, Paris seems to be a good city to be in right now.

FJO: I’ve enjoyed the times that I’ve been there. And, at this point, I imagine you are probably also able to find musicians there who play pipa and shakuhachi and any other instrument you’d want to write for.

BCL: Well, these other musicians are in Seattle or New York. I think for the variety of multicultural things, the United States is still the best. In Germany, there are some people. Wu Wei is there. And I just did a piece for a pipa player in Geneva. There are so many pipa players everywhere now, and they’re all very, very good.

FJO: Are they all Chinese?

BCL: Yes.

FJO: There’s now all this repertoire for Asian instruments that’s part of Western contemporary music, either in combination with Western instruments or just for those instruments, even pieces that are being composed by people who are not originally from Asia. But most of the players are still Asian, even though there are now some really terrific shakuhachi players who are not Asian. With the other instruments, like pipa, that hasn’t happened so much yet.

BCL: I think it’s going to change soon. Hasn’t Manhattan School of Music started a Chinese music program? And in the Midwest, there are centers. There are Confucius Institutes all over the world. They all have music programs. So it’s changing. It’s going to take a while, but before too long, it might be very cool to learn to play pipa. The Silk Road is everywhere, so people may want to learn that.

FJO: Now in terms of big projects, you said writing a symphony is very hard. But you’ve done two rather large music-theater type pieces. The one that I’m more familiar with is The Child God. It’s a big piece.

BCL: That’s only half an hour.

FJO: Yeah, but many symphonies are about a half an hour, unless you want to be Mahler.

BCL: No, I don’t want to be Mahler. You cannot be Mahler. I don’t want to be Respighi, either. I want to be me. But Mahler is such a great composer; I’m not in the same league.

FJO: So what pieces would you want to write if you were given the opportunity to write them?

BCL: I don’t really have any goal or wish, just what comes to mind. I have to work on this youth orchestra piece. That will be 25 minutes. So that can be a symphony.

FJO: There you go. There’s your symphony.

BCL: Yeah, but I don’t want to call it a symphony. It just has too much implication somehow. Symphonies, symphonias, everybody playing together—that’s the original definition. I want to start with number nine, and I will die right away.

FJO: Well I hope that doesn’t happen. So don’t write that one yet.

BCL: Yeah, I’m postponing it. Until I’m 95, then it’s about time to go.