Using a different number of notes per octave, it is possible to write new music with new harmonic relationships that humankind has never heard before.

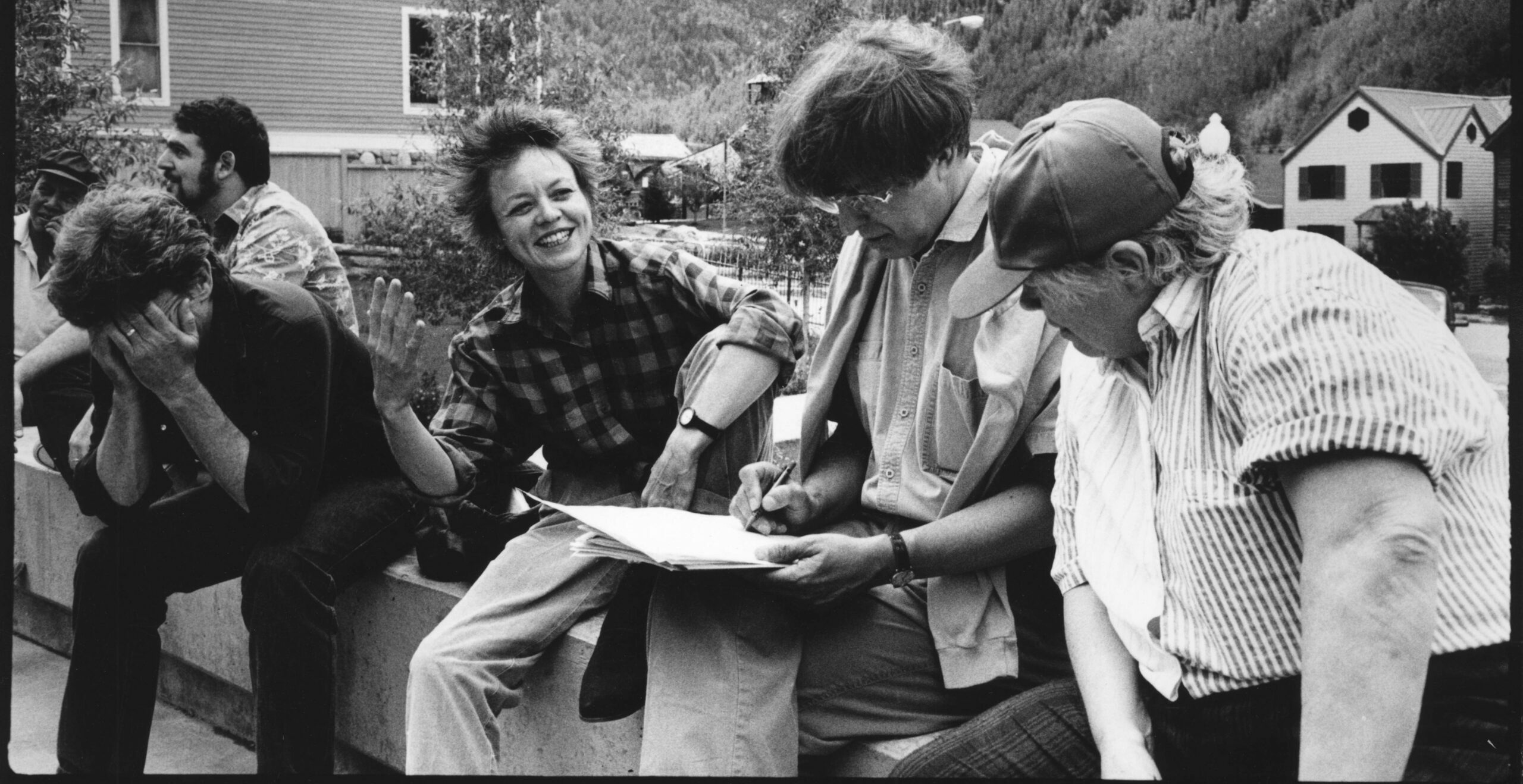

Despite his fascination with extremely dense structures, California-based composer Chris Brown is surprisingly tolerant about loosely interpreting them. Chalk it up to a musical career that has been equally devoted to composing and improvising.

As a young and very green teacher of both classroom and private students, I have no illusions about making mistakes in my teaching. Teachers face challenges in managing many different personalities in a classroom, particularly in equating vocality with interest or aptitude.

We must build greater gender and racial diversity into curriculums and concert programs so that students may see themselves in history.

In the 1980s, OPERA America members became concerned with the dearth of new American operas and the stagnation of standard European repertoire. In response to this perceived crisis, they decided to take action. But the need for financial support was only part of the problem.

The vast number of people in this world that the great Geri Allen has influenced is undeniable. She has been an outstanding musician, mother, educator, mentor, and role model to many—including myself.

In October of last year, Ashley Fure became a mentor to me without her knowing it. Beyond the striking impression of the music, I was moved by Fure’s comments about it.

Why is it important to include women in curriculums or histories? Why is it important that women’s contributions are visible? If they’re not, we run the risk of their absence being accepted as some kind of unquestionable natural state. We need to actively resist this by ensuring women and their music are present in our classrooms and concert halls.

Anyone who knew her would agree that multifaceted composer, musicologist, teacher, Schoenberg disciple and punk rock singer Dika Newlin (1923-2006) was one of the most brilliant, eccentric people they ever encountered. Her extant works certainly deserve to be rediscovered. But for her multimedia pieces, it is almost certainly too late.

In the wake of questions surrounding SoundCloud’s future, it may seem important to quickly figure out “What service do I use now?!?” But Gahlord Dewald suggests that we might first take this opportunity to clarify our goals when we share our music online, and then let those answers lead us to the best tools. He’s found several to get you started. What would you add to the list?

Having someone as a mentor figure who was outside of music–Vickie Sullivan, a popular professor at Tufts University particularly well known in the political science and classics departments–was really grounding: it reminded me that my art and the skills I need to make it didn’t exist in a vacuum.

Tara Rodgers chats with Anne Lanzilotti about electronic music, gear, gender, and the ways in which music is a starting point for exploring questions of belonging and nonbelonging, of identity and difference.

Today is a net neutrality day of action! New Music USA is certainly interested in preserving a free and open internet and has filed a comment with the FCC to this effect. Eddy Ficklin outlines what’s at stake–especially for creative artists–and shows you how to submit a comment of your own.

Kati Agócs was a patient and thorough teacher who guided me like the complete beginner I was but treated me like a professional. I was such a sponge because I was able to see a person I so deeply admired that might one day be me.

LPs and CDs package music with a wealth of information—liner notes, additional images, studio details, and lists of personnel. For newer digital releases and libraries of files that carry only a handful of metadata fields, their absence suggests that the music can somehow meaningfully exist without such information. Marc Weidenbaum argues that it can’t.

One of Anne Lanzilotti’s favorite things about teaching is that curriculum is alive and therefore must be nourished so that it may change over time. That means constantly reading and learning from colleagues and students about new music and new approaches to sound.

How do we critique each other’s work? What is at stake in such a conversation? For every successful endeavor, there are more failures. As I became aware of this contingency, “What do you think?” became an increasingly high-stakes question.

Over the next few months, we’ll be sharing case studies that illuminate networks of support for new American music, as presented by a panel of musicologists at the third annual New Music Gathering this past May. The full series is indexed here.

Composer/vocalist Kristin Norderval’s output has been extraordinarily diverse but addressing societal wrongs is perhaps the one common focus that unites decades of work whether she’s improvising vocals and transforming sounds on her laptop alongside other musicians, performing with the viol consort Parthenia in a song cycle she wrote for them, creating electronic scores for dance, building sound installations involving upturned pianos or repurposed trash, or starring in her own evening-length opera about an abduction during the Argentinian junta, The Trials of Patricia Isasa, which premiered last year during the 2016 OPERA America conference in Montreal.

The moment you start thinking about making a recording is when you should also begin thinking about how you’re going to promote it. Andrew Ousley concludes his series by walking you through the process step-by-step.

In a comic book or graphic novel, there may be little lines that suggest a tiny burst of noise or emblazoned effects—words writ large in blocky colorful type—that announce the intrusion of sonic events. Sometimes there are even actual musical notes. This week, Marc Weidenbaum explores what the reader “hears” off the page.

There are tools you need before you can do any sort of publicity or marketing around yourself and your music. The primary materials are photos, videos, audio recordings, a bio, and a website to tie them all together.

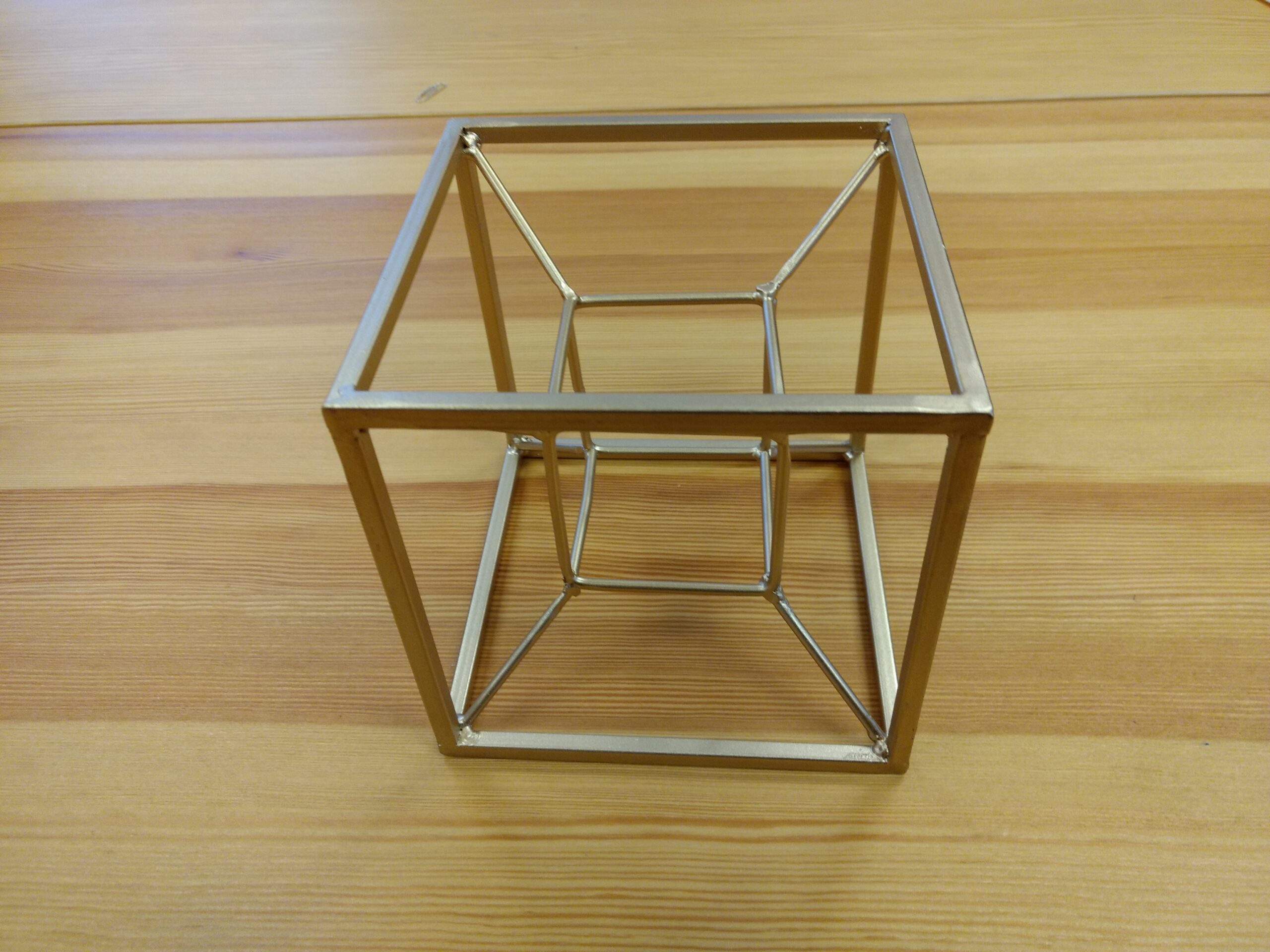

Is the printed circuit board a form of musical notation? And even if it isn’t, what can one glean from all those diodes, the cryptic copper lines, the tiny landscapes of circuitry?

The annual get together of members of the Music Publishers Association of the United States at the Redbury Hotel in New York City combined a luncheon, legal and copyright updates, lively panel discussions, and an award ceremony, and concluded with a cocktail hour.